Научно-исследовательский институт проблем каспийского моря

| Вид материала | Документы |

- Научно-исследовательский институт проблем каспийского моря, 10916.68kb.

- Институт каспийского сотрудничества, 668.69kb.

- Методические указания му 1 2600-10, 485.46kb.

- Рыбохозяйственные и экологические аспекты эффективности искусственного воспроизводства, 422.61kb.

- Свод правил по проектированию и строительству метрополитены дополнительные сооружения, 1496.85kb.

- согласован мчс россии письмо n 43-95 от 14., 1639.07kb.

- Оценка ситуации в регионе Каспийского моря и прикаспийских государствах в апреле 2011, 416.63kb.

- «Научно-исследовательский институт дезинфектологии», 448.62kb.

- Методические рекомендации мр 6 0050-11, 382.97kb.

- Решение IV международной научно-практической конференции, 42.94kb.

Библиографический список

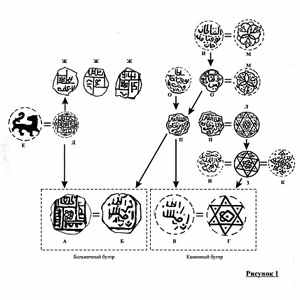

- Клоков В.Б. Лебедев В.П. Монетный комплекс с Селитренного городища // ДПДР Вып.IV Н. НовгородЮ 2002.

- Клоков В.Б. Лебедев В.П. Денежное обращение Сарая и его округи // ДПДР. Вып V М.- Н.Новгород, 2004.

- Лебедев В.П. Павленко В.М. Бугарчев А.И. Комплекс медных монет с Маджарского городища // Труды международных нумизматических конференций. М., 2005.

- Арсюхин Е.В. Студитский Я.В. О генезисе некоторых типов монет Крымско-Азакского круга // Труды международных нумизматических конференций М., 2005.

Е.М. Пигарёв

ОГУК «Астраханский государственный объединенный

историко-архитектурный музей-заповедник»

ИНВЕСТИЦИОННЫЙ ПРОЕКТ ПО СОЗДАНИЮ И КОМПЛЕКСНОМУ РАЗВИТИЮ (МУЗЕЕФИКАЦИИ) ИСТОРИКО-АРХЕОЛОГИЧЕСКОГО И ПРИРОДНО-ЛАНДШАФТНОГО МУЗЕЯ-ЗАПОВЕДНИКА

«ВЕЛИКАЯ СТЕПЬ»

(рабочий вариант)

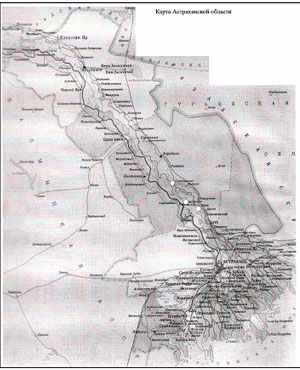

На территории Харабалинского района Астраханской области находятся три объекта историко-культурного наследия, два из которых – Селитренное городище и Хошеутовский Хурул – являются памятниками федерального значения (рис.1).

Селитренное городище является остатками столицы Золотой Орды (XIII-XV вв.) города Сарай (Сарай аль-Махруса, Сарай аль-Джедид, Сарай Бату) – одного из крупнейших городов средневековой Евразии. Охранная зона памятника 2061,5 га.

Комплекс мавзолеев у пос. Лапас (Ак-Сарай) является некрополем золотоордынских ханов и сарайской аристократии (XIV-XV вв.). Охранная зона памятника 197 га.

Хошеутовский Хурул буддийский храм, памятник архитектуры XIX в. Построен в 1818 г. на средства владельца Хошеутовского улуса Калмыцкой степи Астраханской губернии Сербеджаба Тюменя в ознаменование победы в Отечественной войне 1812 г. Архитектурная площадь памятника 200 м2.

Кроме того, на территории Харабалинского района находится ряд привлекательных природных объектов. Селитренное городище расположено на левом берегу реки Ахтуба, на бурых полупустынных, супесчаных почвах с изреженной растительностью, пересеченных цепями бугров Бэра, имеющими единую ориентацию по линии юго-запад – северо-восток. В районе центральной части городища на берегу Ахтубы имеется удобный песчаный пляж. В 1 км от берега находятся два соленых озера, вода которых отличается лечебными свойствами. В разнообразной степной растительности особое место занимает небольшая плантация мексиканских кактусов (опунция). В песчаных котловинах, находящихся в восточной части городища имеются выходы кристаллов природного гипса – «гипсовые розы».

В районе пос. Лапас находится западная граница Волго-Уральской пустыни с песчаными массивами, уходящими на восток.

Хошеутовский Хурул, находится на территории села Речное, расположенном на живописном берегу р.Волга.

Природные объекты и условия делают посещение Харабалинского района по музейному маршруту еще более привлекательными.

Обилие исторических и природных объектов на территории одного Харабалинского района дало возможность специалистам Астраханского музея-заповедника, при поддержке администрации МО «Харабалинский район», разработать Инвестиционный проект по созданию и комплексному развитию (музеефикации) Историко-археологического и природно-ландшафтного музея-заповедника «Великая Степь» - филиала ОГУК «Астраханский государственный объединенный историко-архитектурный музей-заповедник».

Доступность объектов. Все три, обозначенных объекта расположены вдоль автотрассы Астрахань-Волгоград. Расстояние от областного центра до пос.Лапас 70 км, до с.Селитренное 120 км, до с.Речное 110 км по трассе и 30 км по ответвленной асфальтированной дороге. Кроме того, до с.Речное возможен подъезд на речном транспорте.

Посещаемость района. На территории Харабалинского района находится более 50 туристических баз (более 500 на территории Астраханской области). В весенне-летний период Харабалинский район посещают или проезжают через его территорию более 150 тыс. человек.

Работа по созданию имиджа. Селитренное городище в результате проведенного в 2007 году конкурса получило статус «8 чудо света от Астраханской области». В честь этого события звезда из созвездия Весов получила имя «Сарай Бату». На протяжении двух лет на территории Селитренного городища (впервые в России) проводится межрегиональный праздник «15 августа – День археолога».

Селитренное городище (рис.2).

«Город Сарай – один из красивейших городов, достигающий чрезвычайной величины на ровной земле, переполненной людьми, красивыми базарами и широкими улицами… В нем тринадцать мечетей для соборной службы… Кроме того, еще чрезвычайно много других мечетей… В нем живут разные народы, как то монголы…, асы…, кипчаки, черкесы, русские и византийцы. Каждый народ живет в своем участке отдельно, там и базары их». Таким увидел Сарай арабский путешественник Ибн-Батута в 30-х гг XIV века. Город Сарай, Сарай ал-Махруса – столица улуса Джучи – в научном мире более известный, как Селитренное городище, расположен на берегу реки Ахтуба в Харабалинском районе Астраханской области. Селитренное городище является памятником археологии федерального значения и считается, по праву, одним из крупнейших археологических объектов Российской Федерации.

Развалины золотоордынской столицы издавна привлекали к себе внимание путешественников и исследователей. Целый ряд ученых оставил описание городища: И.П. Фальк, П.С. Паллас, И. Потоцкий, М.С. Рыбушкин, И. Шеньян, А.В. Терещенко, Н.П. Загоскин, А.А. Спицын.

Первые по настоящему научные раскопки городища были проведены в 1922 г Ф.В.Баллодом, который снял его план, условно разбил город на семь районов, дав им социальную характеристику, провел классификацию находок.

С 1965 г. Селитренное городище исследуется Поволжской археологической экспедицией ИА РАН, руководство которой осуществлялось А.П. Смирновым, Г.А. Федоровым-Давыдовым, В.В. Дворниченко. За десятилетия изучения города в руки ученых попала богатейшая археологическая информация, с помощью которой было изменено представление об улусе Джучи как о кочевом государстве с малочисленными и слаборазвитыми городами. К настоящему времени на городище полностью исследовано более 30000 м2. Интенсивные работы экспедиций позволили реконструировать цивилизацию Золотой Орды, представляющей собой симбиоз двух миров – городской культуры и степной стихии кочевников. В процессе раскопок были раскрыты многочисленные жилища рядовых горожан, усадьбы и дворцовые конструкции золотоордынской аристократии, погребальные и производственные сооружения, бани и культовые постройки. В ГИМе, Эрмитаже, Астраханском музее-заповеднике хранятся многочисленные коллекции предметов - керамические сосуды, изделия из металлов, кости – найденных во время раскопок, показывающих всю многогранность материальной культуры Золотой Орды.

Постановлением Совета Министров РСФСР №1327 от 30.08.1960 г. Селитренное городище было признано памятником археологии государственного значения. Была определена охранная зона городища и зона регулируемой застройки, разработаны режимы ее использования, гарантирующие сохранность памятника от воздействия хозяйственной деятельности человека. В 2002 г. был составлен Паспорт памятника, в котором утверждена новая, значительно увеличившаяся, охранная зона (2061,5 га).

В 1969 г. впервые принимается решение о музеефикации Селитренного городища. В 2003 г в целях дальнейшего изучения и сохранения памятника началось создание музея «Селитренное городище», являющегося филиалом ОГУК «Астраханского государственного объединенного историко-архитектурного музея-заповедника» (АГОИАМЗ). Это позволило не только увеличить масштабы исследовательских работ на городище, но и более продуманно подойти к проблеме сохранения памятника, как объекта историко-культурного наследия народов Российской Федерации.

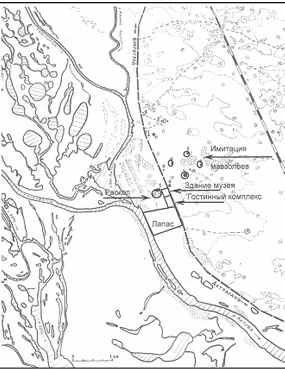

Комплекс мавзолеев у пос.Лапас (рис.3).

В 40 км ниже Селитренного городища у села Лапас находится крупный памятник золотоордынской эпохи. Здесь на берегу реки Большой Ашулук обнаружены небольшой поселок строителей и гончаров и, расположенный в степи золотоордынский некрополь. В ходе работ Поволжской археологической экспедиции были зафиксированы остатки 14 памятников средневековой погребальной архитектуры. Пять крупных мавзолеев образуют две аллеи, к которым примыкают сооружения более мелких размеров. Современные исследователи считают, что в четырех крупнейших мавзолеях Лапаса погребены четыре хана-мусульманина: Берке (1257-1267), Узбек (1312-1341), Джанибек (1341-1357), Бердибек (1357-1359).

Местоположение некрополя отмечено на итальянской карте 1367 года братьев Пицигани с латинской надписью «Гробницы императоров, умерших в районе Сарайской реки».

Сведения об этом некрополе имеются в «Книге путешествия» турецкого дипломата Эвлии Челеби, посетившего Нижнее Поволжье в 1665-1666 гг. Им приводятся следующие сведения:

Из раздела «По поводу нашего подъема вверх по реке Волге»:

«Затем, после Астрахани, на расстоянии дневного перехода по берегу Волги находится стоянка Бештепе – пять высоких гор правильной формы. Их верхняя часть – искусственная, это насыпные горы, наподобие трех священных гор, находящихся в Египте в окрестностях Гизы. Каждая из упомянутых пяти гор видна с расстояния трех дневных переходов».

Из раздела «О причине разрушения города Сарая»:

«И на высоком пороге каждой гробницы, на каменных плитах могил, отчетливым почерком написано: возраст и годы жизни обладателя могилы, его добрые дела и прекрасные свойства, перечислено все, чем он в своей жизни владел, что совершил, каким человеком был. То редкостные памятники удивительного народа».

Анализ исторических событий, происходивших в XIV веке на территории Золотой Орды, и нумизматического материала, полученного в ходе исследований памятника, позволяют с большой степенью уверенности связать образование некрополя (и центрального (№1) мавзолея) с именем хана Узбека, утвердившего в Золотой Орде ислам государственной религией.

Хошеутовский хурул.

Хошеутовский хурул – буддийский храм, памятник архитектуры XIX в. Построен в 1818 г. на средства владельца Хошеутовского улуса Калмыцкой степи Астраханской губернии Сербеджаба Тюменя в ознаменование победы в Отечественной войне 1812 г. Авторами проекта выступили Батур-Убуши Тюмень и буддийский священнослужитель Гаван Джимбе. Храм был построен вблизи Тюменевки – родового поместья рода Тюменей, на месте старого деревянного хурула. Ансамбль сооружений Хошеутовского хурула состоял из молельной, центральной башни и двух галерей, отходивших от нее полукругом и заканчивавшихся двумя малыми башнями. Храмовый комплекс объединял четыре хурула: Ики хурул (собственно Хошеутовский хурул), Большой Манлы, Большой Докшадын, Малый Цацан. В начале XX в. в хуруле было 35 монахов. В 1867 и 1907 гг. были проведены реконструкции храмового комплекса. В 1926 г. В Хошеутовском хуруле было 17 гелюнгов и 14 манджи. В 30-е годы XX в. богослужения в хуруле были приостановлены, здание было передано детскому саду, позднее хурул становится школой и зернохранилищем. В 60-е годы XX в. были снесены галереи и малые башни хурула. Решением исполкома Астраханского областного Совета депутатов трудящихся от 14 ноября 1967 года Хошеутовский хурул был принят под охрану государством как памятник истории и культуры местного (областного значения). В сентябре 1989 года руководством Калмыцкой АССР и Астраханской области было принято решение о начале работ по реставрации памятника, был создан оргкомитет и определены задачи реставрационной деятельности. В 1991 году объединением «Росреставрация» были начаты работы по восстановлению памятника. В декабре 1995 года Хошеутовскому хурулу была присвоена категория памятника федерального значения.

Концепция музейного комплекса должна соответствовать традициям и основным категориям буддийской культуры приволжских калмыков, исторической роли калмыков в судьбе России, символичности данного объекта. Основой существования музейного комплекса представляется форма «музей-храм» - тем самым не будут ущемлены права верующих-буддистов Республики Калмыкия и Астраханской области и будет сохранен памятник истории и культуры.

Цели, преследуемые проектом:

- создание особо охраняемой территории - Историко-археологического и природно-ландшафтного музея-заповедника «Великая Степь», в состав которого будут входить: Селитренное городище (остатки столицы Золотой Орды города Сарай ал-Махруса, XIII-XIV вв.); Ханский некрополь у пос. Лапас (XIV-XV вв.); Хошеутовский хурул (XIX в.);

- научное изучение объектов, входящих в состав музея-заповедника «Великая Степь»;

- обеспечение сохранности наследия материальной и духовной культуры средневекового государства Улус Джучи;

- развитие туристической инфраструктуры на территории музея-заповедника «Великая Степь».

Задачи, поставленные перед разработчиками проекта:

- археологическое изучение, реставрация и музеефикация архитектурных объектов Селитренного городища и Ханского некрополя у пос. Лапас;

- строительство зданий музеев на Селитренном городище и Ханском некрополе у пос. Лапас, оформление их экспозиций; оформление экспозиции музея-храма в Хошеутовском хуруле;

- издание научной и научно-популярной литературы и сувенирной продукции.

Реализация данного проекта приведет к созданию на территории Харабалинского района Астраханской области еще одного крупного в Российской Федерации музейного, научного и туристического центра, что будет не только благотворно влиять на сохранение археологического наследия, но и станет основой для экономического развития территории.

ПРИЛОЖЕНИЕ

Рис.1.Карта Астраханской области с обозначением памятников, находящихся на территории Харабалинского района.

Рис.2. План-схема Селитренного городища с размещением музейных объектов.

Рис.3. Схема расположения музейного комплекса у пос. Лапас.

АСТРАХАНСКИЙ КРАЙ В XVI-XXI ВВ.

Arno Johannes Langeler

University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

DUTCH AND RUSSIAN CARTOGRAPHERS AND DESIGNERS, WINIUS, WITSEN AND OTHERS

Lately, I noticed a doctorate dissertation written by the Dutchman Igor Wladimiroff, De kaart van een verzwegen vriendschap, Nicolaes Witsen en Andrej Winius en de Nederlandse cartografie van Rusland, ( the map of a concealed friendship, Nicolaes Witsen and Andrej Winius and the Dutch cartography of Russia), Groningen 2008. This book seems to me as very important for clearing some relations between The Netherlands and Russia in the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries. The author, a descendent of Russian emigrants, has composed an interesting and enlightening book, written in a very readable style. Immediate cause for his writing was the beautiful Russian map of Nicolaes Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam and “devotee cartographer”,drawn in 1687 and published in 1689: De Nieuwe Landkaarte Van het Noorder en Ooster deel van Asia en Europa Strekkende van Nova Zemla tot China Aldus getekent, Beschreven, in Kaart gebragt en uytgegeven sedert een nauwkeurig onderzoek van meer als twintig jaren door Nicolaes Witsen. Anno 1687 ( A new map from the northern and eastern part of Asia and Europe, stretching from Nova Zembla to China, Drawn, written, mapped and edited after a precise investigation of more than 20 year by Nicolaes Witsen. In the year 1687 - see plate 30 in the book of I.Wladimiroff). Because it never became completely clear how Witsen acquired the bulk of the materials necessary for his map of parts of the world that he never visited and a rumour existed that Andrej Winius provided him with some materials, Wladimiroff decided to investigate the relations between Witsen and Winius.

Cartography and some Dutchmen in Russia in the 16th and 17th century

In the first place Wladimiroff paints a picture of the Dutch mercantile contacts with Russia and the influence of their cartography in that respect. Some influence of the Flemish and Dutch activities was attributed to contacts between historian, and medic Paolo Giovio and the ambassador of grand-duke Vasilij III the translator and diplomat Dmitrij Gerasimov who paid a visit to pope Clemens VII in 1525. From the hand of Giovio was the outcome of this encounter the Novocomensis Libellus de Legatione Basilii Magni Principis Moschoviae (the new booklet from Como about the embassy of grand-duke Vasilij) . A map showing Russia was separately edited based on the notices of the Roman Plinius the Elder, suggesting that it was possible to sail from the White Sea through the Arctic to China (1).

The first people from the Low Countries travelling in 1565 from Antwerp to the north of Russia were Philips Winterkoning and Cornelis de Meyer(e) (a distant ancestor of my wife Betty)(2). After the fall of Antwerp to the Spaniards, the mercantile activities of many inhabitants shifted to the new Republic of the United Netherlands, in this case to the northern provinces.

The maps got better and better. After the conquest of the port of Narva by the Swedes in 1581 English and later Dutch ships found their way to the new city of Archangel on the White Sea. A lot of cartographic activities in the Dutch Republic accompanied the mercantile movements. Dutch merchants got in the end the upper hand over the English in Russia. In the relations between the Moscovites and the Dutch, the in Russia active native from Haarlem Isaäc Massa and several Russian embassies to the General States of the Republic and to stadtholder prince Maurits played a significant role. Wladimiroff mentions here the intermediate function of the Amsterdam mayor Gerrit Witsen, an early relative of Nicolaes (3).

The preponderance of foreigners in Russia in commercial matters evoked some xenophobic sentiments. This was for the Dutch an negative factor because some measures to limit the trade of wheat, threatened the Dutch dependency of the grain import from Russia. A Dutch embassy to tsar Michaïl in 1631 to obtain a monopoly on Russian grain export had no success. After the death of Michaïl the situation for foreign merchants worsened. Special envoys did not attain noticeable success. An example of these was the embassy led by Jacob Boreel that visited Moscovia and Moscow in 1664 and 1665. The young Nicolaes Witsen took part in this embassy, wrote a diary and made some remarkable drawings of spots he passed on his way to Moscow (4).

The silk trade was very important to the Dutch. For that reason they sent in 1675 Coenraed (van) Klenck to the tsar. He knew that the attempt of the Russians to establish in Astrachan their own trading post with Persia was shattered through the uprising of Stepan Razin, and therefore he came with the request to explore by the Dutch a new way through Siberia to Persia and China. His second demand was a Russian participation in the war against Sweden – an ally of the French who were in that time in a state of war with the Republic. In spite of the confidence and hospitality Klenck enjoyed at the Russian court, he went home with empty hands. Main reasons were the distaste to grant foreign merchants special privileges and the unwillingness of the tsar to wage war with Sweden(5).

Russia in Dutch cartography

To the foremost Dutch cartographers in the 17th century belonged the family Blaeu, three generations, manufacturing maps and atlases in Amsterdam. Wladimiroff refers to the Atlantis Appendix of Willem Blaeu with maps of Moscow and the Kremlin, made around 1630. He says: “ The source of that map of Moscow was to all probability the ….inset map of tsar Boris Godounov….The plan of the Kremlin is without doubt from Russian origin and had been possibly taken along by Massa”(6). These maps were in 1665 also published in the Atlas Major by his son Joan Blaeu, with for the Kremlin extensive explanation. Very interesting is in this atlas the river chart of the Volga. This map was based on a chart, made by the German Adam Olearius, who in 1633 paid a visit to Russia as member of an embassy sent by the duke of Holstein to the tsar. A few years later he organized an expedition to the South East in the direction of Persia in order to trade with that country. Due to a bad preparation this enterprise failed(7). Wladimiroff mentions the cooperation between Olearius and a certain Cornelis Kluyting, a Dutchman. In 1636 Kluyting got permission from tsar Michaïl to act as a pilot on the ship that carried Olearius across the Volga to the Caspian Sea. Kluyting was not only a sailor, but also a technician. He assisted Olearius in mapping the Volga and its estuary into the Caspian. Later, in 1658, only after the publication of Olearius’s diary in the Republic, the cartographer Jan Jansz. Janssonius edited Nova et Accurata Wolgae fluminis, olm Rha dicti delineation Auctore Adamo Oleario (a new and accurate map of the river Volga, of old called the Rha, by the hand of Adam Olearius). The same map was published in the Atlas Major and used for corrections by Nicolaes Witsen on his journey to Moscovia.

The next person that appears in Wladimiroff ‘s description of important Dutch maps of Russia is Jan Struys. “Under the command of Butler and skipper Lambert Jacobsz. Struys (she) sailed.across the Volga and the Caspian Sea in the direction of Persia. Along the way, however, the Orel , near Astrachan, was taken by the rebel leader Stenka Razin. Struys got into captivity, but escaped later”(8). Here Wladimiroff was somewhat inaccurate: the crew of the Orel was partly inside Astrachan where she was taken prisoner by Razin during the capture of the city. Some tried to escape before the final attack of the Cossacks on the city. The Orel deprived of heir cannons laid defenceless on the quayside and got destructed – at which moment exact is not known (9).

Annex to Struys’s travel report was a Zee Kaert Verthonende de Kaspische Zee (sea chart showing the Caspian Sea) (10).

Witsen

Nicolaes Witsen made his personal acquaintance with Russia through his voyage to Moscow in 1664 and 1665. His Diary shows how greatly that country had him impressed. In Moscow he was able to make a lot of observations: about the looks and behaviour of tsar Aleksej and the common people, the appearance of the Kremlin, the housing, the religion and the administration of the law. Witsen was assisted by Andrej Winius, his second cousin, interpreter for the tsar and member of the posolskij prikaz. However, in his diary Witsen never mentions his name, but only refers to a friend who was very helpful to him. The leader of the Dutch embassy, Boreel, records several occasions where Winius acted as interpreter (11).

After his return to Amsterdam, Witsen stayed the rest of his life interested in Russia, not only in political and economic matters, but also in the geography in that country. First, he made, following many others of his class, a grand tour through Europe: he visited Paris, Lyon, Milan, Florence and Rome. He returned via France and Cologne. After the death of his father Cornelis in 1669, Witsen was obliged to gain – in the tradition of his family - his own position in the city administration of Amsterdam. In 1672, the Dutch Year of Wonders, he was put in charge of the defence of the city during the invasion of the French and two German bishops. Somewhat later he became one of the mayors and assisted in 1688 and 1689 politically stadtholder William III in his Glorious Revolution in England (12).

Besides his work as administrator of Amsterdam. Nicolaes Witsen spent a lot of time on his investigations. The books published by him give some evidence of his exertions. The first of them, Aeloude en Hedendaegsch(z)e Scheepsbouw en Bestier (Old and Present Shipbuilding and Steering) appeared in 1671. The price of the book was 12 guilders, a considerable amount. In his foreword Witsen utters his amazement that no earlier book on ships and their equipment had been published in his maritime country. The Scheepsbouw en Bestier was a rather popular work; “from Sweden to Italy and from Moscovia to Batavia one could find copies in the libraries of wealthy scholars, notwithstanding the fact that the work was written in the Dutch language. Proof for the popularity turns up from the letters of the German savant Gottfried Leibniz and from the well-known diplomat and poet Constantijn Huygens who evoked the interest of the English king Charles II.- for us a remarkable fact; in that time a full war was going on between England and the Dutch Republic.(13 There was some criticism on several passages in the book. In his description of the battle between the Dutch and the Swedes in the Oresund (1658), Witsen stated that the Swedish admiral, count Karl Gustav Wrangel had deserted the battle because he was hit by a bullet in his jaw “however his ship was named the Victoria”. Wrangel, in possession of the Scheepsbouw and Bestier was furious, because his ship was so damaged that he was not able to continue the fighting, In a letter, he complained to Witsen, with result. The author changed some pages: he named Wrangel manhaft (brave) and his son who was killed in that battle a hero. In reaction thereupon Wrangel called Witsen an honnête home (14)

In a short time, the book was a antiquarian rarity. In 1690 a second appeared edited by the firm Pieter and Joan Blaeu, a fact that was only discovered in the beginning of the 20th century. Wladimiroff is very restricted on Scheepsbouw en Bestier. Marion Peters, on the other hand, introduces in her The wijze koopman (see n.13) a lot of sketches of ship types – mostly made by Nicolaes Witsen himself. This goes for Dutch and foreign vessels alike. The edition of 1690 contains the Russisch-Vaar-tuigh (Russian vessel),a special and new part of chapter 16 of part 1 with 7 images of Russian ships - made by anonymous artists.(15 Witsen had collected a lot of Russian materials and illustrations for his Noord en Oost Tartarije (North and East Tartary), published in 1692, second edition in 1705 and long after his death in 1785.

A new edition of Noord en Oost Tartarije is forthcoming, so I restrict myself to some cartography in his work. Already, during his visit to Moscow, Witsen had a conversation with Gerrit Kluyting about the geography of the Caspian Sea and the surrounding area’s. Witsen was allowed the make a copy of the map of the Caspian region made by Kluyting’s brother Cornelis. Later, he inserted this map in his Diary and became known as the Het Caspise Meer....Na de origineele Teeckningh, in Mosco afgemaeckt. Ao 1665. Nicolaus Witsen (The Caspian Lake….After the original drawing, in Moscow copied. In the year 1665. Nicolaus Witsen (16).

Wladimiroff enumerates a number of maps in both the editions of Noord en Oost Tartarije. Several of them were designed by Witsen himself, other were copies from already existing charts – sometimes mistakenly attributed to himself. In this respect is map 3 important: Het suydelykste gedeelte van de Vliet Wolga in Kaert gebragt volgens de jongste verbeteringe van den Heer E.Kempfer, uit de miswysinge van’t Compas en andersints gerigt, door N.Witsen, Cons.Amst. MDCXCVII. (The most southern part of the river Volga, mapped according to the most recent improvements of mr. E.Kaempfer, as consequence of the false indications of the compass, and (therefore) directed in another direction, by N.Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam, 1697. This means that this map was not taken down in the first edition of 1692. This Kaempfer , a German, medic and collector, was secretary to the Swedish envoy Lodewijk Fabricius, from birth a Dutchman, who travelled in 1683 through Russia to the Sjah of Persia in Isfahan. He was a friend of Witsen’s. “Under the authority Kaempfer worked as a correspondent for Witsen” (17).

Another map – not in the first edition – is Nieuwe kaert vande omtrek der Swarte Zee uyt verscheydene stucken van die gewesten toegezonden, ontworpen door N.Witsen, Cons:Amste. MDCXCVII. (A new map of the outline of the Black Sea, sent from various parts of those regions, designed by N.Witsen, mayor of Amsterdam. !697. Wladimiroff sees a similarity with older Italian maps. In 1723 made the Amsterdam publishers Ottens a copy of Witsen’s map (18).

In the first edition one can find Palus Maeotis, in kaartgebragt door N.Witsen, MDCXC.( The sea of Azov, charted by N.Witsen, 1690. The name Palus Maeotis is derived from Ptolemaeus. The exact source is not known; there are many examples for this map.(19

Winius

Cousin and one of the dearest friends of Nicolaes Witsen in Russia was Andrej Andrejevitsj Winius. He, the son of the Dutch merchant in Russia and therefore because of his knowledge of the Dutch language, was acting as interpreter for the tsar. So he came in contact with foreign diplomats. In 1665 he met Witsen. Working as an interpreter brought Winius also in contact with the Dutch shipbuilders in Dedilovo on the Oka that were constructing two vessels for sailing the Volga and the Caspian Sea. Wladimiroff speaks about a frigate, but the greatest of the two was probably a pinas. On this way, the Russians hoped to control the profitable trade with Persia. The Dutch gostj Jan van Sweeden advised the tsar to hire a Dutch crew. First, he got the commitment of the General States of the Republic, thereafter, captain David Butler – a Dutchman – was sent to Amsterdam, where he recruited 15 artisans and sailors (20).

After 1689, the year in which Peter became the actual ruler of Russia, Winius became one of the intimates of the tsar. He was nominated as postmaster-general and got in correspondence with the tsar about things like shipbuilding, the war in the Southern Netherlands against the French where Witsen was active as delegate of the States and about a big fire in the main iron foundry in Sweden – important for the production of cannon for France. Witsen was the source of this topic. The embassy of tsar Peter to West Europe was announced in the end of 1696; Winius should stay in Moscow for reason of communication with Peter. Wladimiroff mentions a letter from Peter, written in Riga, to Winius: “....keep this letter above a fire – it is written in invisible ink – and you can read it….But to avoid suspicion, I shall write on the same paper with normal ink”(21).

Winius’s relations with Witsen were intensified by his cartographic activities. Around 1689 Andrej Winius drew a map of Siberia on base of sketches of the road from Moscow to Peking made by the envoy Nicolae Spathary-Milescu, who travelled in 1675 on behalf of tsar Fjodor to the emperor of China. In 1695 Winius became head of the Sibirskij prikaz. As such, he had to accomplish his charting of the vast space of Siberia. The goal was in the first place an economic. The opening up was meant for indicating new roads that were suitable for trade with adjacent countries and for defining the border regions. In the chart-room of the Sibirskij prikaz in Moscow were besides maps of Siberia the most famous atlases available, Ortelius, Mercator and Blaeu. Winius worked together with the cartographers Remezov, father Uljan and sons Leontij and Semjon (22). In 1701 Winius and Semjon Remezov published their Tsjertjoznaja Kniga Sibiri – two of the copies are known with the Dutch title Caertboek van Siberië. One came in the Netherlands and was named in the legacy of Nicolaes Witsen. After the auction in 1761 of the books of Witsen, during which the book was described as Een vertaling (translation) van het Groot Sibirs Caartboek; the atlas have not been heard of since. The second copy lies in the Public Library in Moscow (23). One can assume that a lot of data and peculiarities on Siberia were borrowed by Witsen from Winius for his second edition of Noord en Oosr Tartarije in 1705.

In 1703 Andrej Winius lost for what reasons the grace of tsar Peter. Relations between Witsen and Winius remained good. Proof of that fact one can find in letters that Witsen wrote to Winius. Also gifts bear witness of their mutual cordiality. A example of this concerns Reizen over Moskovië door Perzië en Indië, verrykt met 300 konstplaten....(Travels over Muscovy through Persia and India, enriched with 300 artificial plates), Amsterdam 1711 of Cornelis de Bruyn (1652 – 1726/1727. This work was completed in cooperation with Nicolaes Witsen. Around 1712 Witsen presented this book to Winius. Notable to say that in 1722 the editor Gerard van Keulen copied the “Panorama of Astrachan” of de Bruyn as illustration to his Nieuwe Caart van de Caspische Zee....(New map of the Caspian Sea), mainly based on the map of Jan Struys (24).

Marion Peters mentions that Winius stayed in Amsterdam from 1706 till 1708. According to Witsen’s friend Gijsbert Cuper, mayor of the city of Deventer who visited Witsen in 1711, Winius fled to Amsterdam “three or four years ago” after losing all his estates and dignities. Witsen wrote a letter to the tsar and Mensjikov and his intervention had “un tres bon effet”. Winius got mercy and received his confiscated estates (25).

Around 1709, tsar Peter gave his ambassador in the Dutch Republic, Andrej Artamonovitsj Matvejev assignment to order the newest map of Russia, made by the Frenchman Guillaume de L’Isle. In that period, the Amsterdam publishers Jean Covens and Corneille Mortier revealed his Carte de Moscovie, consisting of two parts. This was a sign of the decreasing influence of Witsen and Winius for the cartography of Russia. Another signal was Matvejev’s assignment to explore the possibility of printing a new atlas consisting of 80 maps of all empires of Russia, replacing the Atlas Major made 50 years earlier by Blaeu. The project never came to existence, probably because the Russian authorities supposed the costs too high (26).

Finally

“There is no doubt that Nicolaes Witsen and Andrei Winius have worked together”. Wladimiroff sees as the main obstruction to this observation that they kept their cooperation secret by not mentioning each other’s names in their letters till the reforms and openness of tsar Peter. Before that, Witsen was surely dependent on Winius for preparing his maps on Russia and in particular Siberia and his Noord en Oost Tartarije. The data on Siberia were kept secret – by naming Winius as his source, Witsen could ruin him (27). The friendship between the two men was solid).