Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture across History Учебное пособие

| Вид материала | Учебное пособие |

- Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture, 365.14kb.

- Курс лекций по дисциплине английский язык Факультет: социальный, 440.82kb.

- Учебное пособие соответствует государственному стандарту направления «Английский язык», 2253.16kb.

- Lesson one text: a glimpse of London. Grammar, 3079.18kb.

- Реферат по дисциплине: страноведение на тему: «The geographical location of the United, 1698.81kb.

- Education in great britain, 98.44kb.

- The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 257.28kb.

- Г. В. Плеханова английский язык учебно-методическое пособие, 1565.3kb.

- А. Л. Пумпянский написал серию из трех книг по переводу, 3583.47kb.

- Учебное пособие для студентов факультета иностранных языков / Сост. Н. В. Дороднева,, 393.39kb.

S

8. Science, Art and Music

cience

The Stuart age was also the age of a revolution in scientific thinking. For the first time in history England took the lead in scientific discoveries. The Stuarts encouraged scientific studies. The Royal Society of London for the Promotion of Natural Knowledge was founded in 1645 and became an important centre for scientists and thinkers where they could meet and exchange ideas. Now it is Britain’s oldest and most prestigious scientific institution.

Already at the beginning of the century, Francis Bacon argued that every scientific idea should be tested by experiment. Charles II gave a firm direction “to examine all systems, theories, principles, … elements, histories and experiments of things natural, mathematical and mechanical”. The English scientists of the 17th century put Bacon’s ideas into practice.

In 1628 William Harvey discovered the circulation of blood. This led to great advances in medicine and in the study of the human body. The scientists Robert Boyle and Robert Hooke used Harvey’s methods when they made discoveries in the chemistry and mechanics of breathing.

In 1666 the Cambridge Professor of Mathematics, Sir Isaac Newton, began to study gravity. He published his important discovery in 1684. And in 1687 he published “Principia”, on “the mathematical p

rinciples of natural philosophy”. It was one of the greatest books in the history of science. Newton’s work remained the basis of physics until Einstein’s discoveries in the 20th century. Newton’s importance as a “founding father” of modern science was recognized in his own time. Alexander Pope summed it up in the following verse:

rinciples of natural philosophy”. It was one of the greatest books in the history of science. Newton’s work remained the basis of physics until Einstein’s discoveries in the 20th century. Newton’s importance as a “founding father” of modern science was recognized in his own time. Alexander Pope summed it up in the following verse:Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night:

God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.

Newton was encouraged and financed by his friend, Edmond Halley, who is mostly remembered for tracking a comet in 1683. The comet has ever since been known as Halley’s Comet. In the 17th century there was a great deal of interest in astronomy. Charles II founded the Royal Observatory at Greenwich which was equipped with the latest instruments for observing heavenly bodies.

- Architecture and art

It was no incident that the greatest English architect of the time, Sir Christopher Wren, was also Professor of Astronomy at Oxford. Now he is better known as the designer of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London which was built anew after the Great Fire of London (1666). The larger part of the City was destroyed, and when it was rebuilt, a new law made Londoners build new houses of stone and brick. Sir Christopher Wren was ordered to rebuild the churches destroyed in the Fire. The jewel of the new city was St. Paul’s Cathedral. Almost every other church in the centre of London was designed by Wren or his assistants. Wren also designed the Royal Exchange and the Greenwich Observatory.

Another prominent architect and theatrical designer of the century was Inigo Jones (1573-1651) whose buildings are notable for their beauty of proportion. They include the Banqueting Hall of Whitehall Palace in London and the Queen’s House at Greenwich.

In the 17th century, English painting was greatly influenced by Flemish artists, especially Van Dyck. He spent a number of years at the court of Charles I, who was his patron. Towards the middle of the century, the name of the Englishman William Dobson became as well known as the name of his Flemish colleague. Another native-born English painter was Francis Barlow, who specialized in animal subjects, or scenes of country sports. One of his famous pictures is ‘Monkeys and Spaniels Playing’ (1661). This kind of subject matter was to become immensely popular in the 18th and 19th centuries.

- Music

In music, Viola da Gamba gave way to the violin, and the English finally produced a national composer who wrote operas. Henry Purcell, ‘the father of the English opera’, may be compared to Bach and Handel. Purcell was also a talented keyboard player and song-composer.

His most famous opera was ‘Dido and Aeneas’ is based on the ancient Roman story about a Trojan leader who escaped to Carthage after Troy was captured by the Greeks. There he met Queen Dido who fell in love with him. Dido killed herself when Aeneas left her.

We must also mention here John Bull, the English organist and composer, one of the founders of contrapuntal keyboard music. He is credited with composing the English national anthem, “God Save the King / Queen”. But don’t think that it is to him that we owe the traditional nickname given to Englishmen. “John Bull”, the symbol of a typical Englishman, is the name of a farmer from the pamphlet of John Arbuthnot.

- J

9. Literature

ournalism

T

he political struggle, involving broad masses of England’s population, favoured the development of political literature and laid the basis for journalism. People took a lively interest in all kind of information about the political events of the time. There appeared leaflets with information (the so-called ‘relations’) as well as periodical press. As a result of the rapid spread of literacy and the improvement in printing techniques, the first newspapers appeared in the 17th century. (In fact, the first newspaper was issued to announce the defeat of the Spanish Armada.) The newspaper was a new way of spreading ideas – scientific, political, religious and literary. The social revolution brought about a turn from poetry to prose because it was easier to write about social and political events in prose rather than in verse.

he political struggle, involving broad masses of England’s population, favoured the development of political literature and laid the basis for journalism. People took a lively interest in all kind of information about the political events of the time. There appeared leaflets with information (the so-called ‘relations’) as well as periodical press. As a result of the rapid spread of literacy and the improvement in printing techniques, the first newspapers appeared in the 17th century. (In fact, the first newspaper was issued to announce the defeat of the Spanish Armada.) The newspaper was a new way of spreading ideas – scientific, political, religious and literary. The social revolution brought about a turn from poetry to prose because it was easier to write about social and political events in prose rather than in verse.- John Milton (1608-1674)

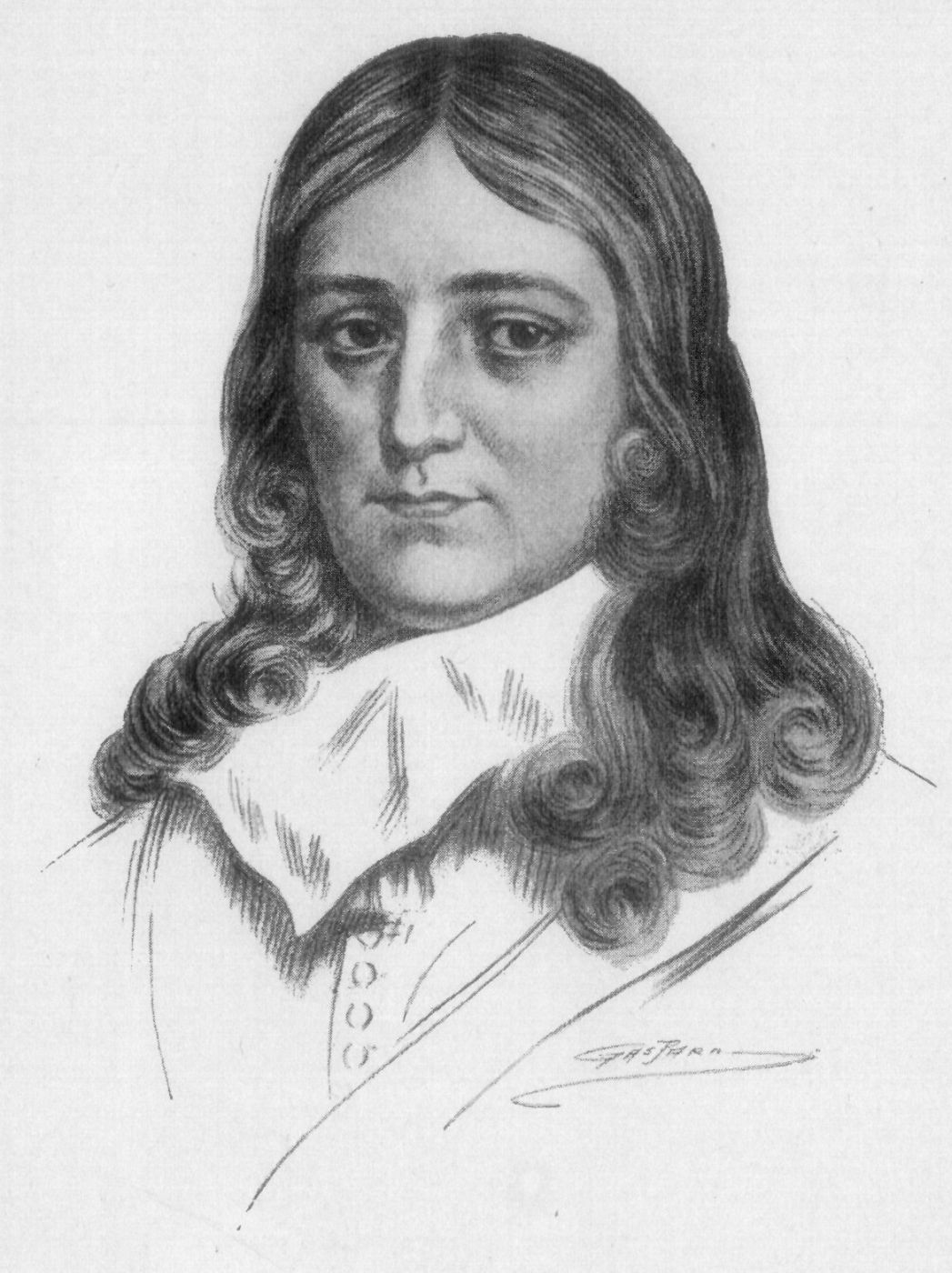

The greatest of all publicists of the Puritan Revolution was John Milton. He was born to a prosperous family on December 9, 1608. Milton’s father, who had received a good education, was an admirer of music and a composer. The poet’s mother is said to have been ‘a woman of incomparable virtue and goodness’.

Milton’s childhood was very different from that of other children. He was little interested in games and outdoor amusements. His father took care of his early education. John learned to love music and books. Milton attended St. Paul’s school. He read and studied so intensely that at the age of 12 he had already developed a habit of working till midnight. At the age of 16 he went to Cambridge University where he got a Bachelor’s and then a Master’s degree. Upon graduation, Milton was asked to remain at the University as an instructor. But he refused, because for him that meant taking Holy Orders – that is becoming a clergyman. He left Cambridge and retired to his father’s country-place Horton, in Buckinghamshire. There, he gave himself up to studies and poetry. Many of Milton’s poems were written in Horton. They form the first period in his creative work.

Milton had always wished to complete his education by travelling, as was the custom of the time. He longed to visit Italy, and his mother’s death, John got his father’s consent to go on a European tour. He visited Paris, Genoa and Florence. The latter won his enthusiastic admiration. The city itself and the language fascinated him. The men of literature, whom he met in Florence, gave him an opportunity to satisfy his thirst for knowledge. Rome, where he went after Florence, made a great impression on him. Milton knew the Italian language to perfection. He spent whole days in the Vatican library. In Italy, he visited and talked to the great Galileo, who was no longer a prisoner of the Inquisition, but was still under the supervision of the Church. Milton’s meeting with the great Martyr of Science is mentioned in Paradise Lost, and in an article about the freedom of the press. After visiting Naples, he wanted to continue his travels, but the news from home hastened his return. Milton considered it wrong to be travelling abroad for personal enjoyment, while his countrymen were fighting for freedom. He returned to England in 1639. For some time, he had to do some teaching. The result of it was a treatise on education.

At the age of 34, Milton married Mary Powell, the daughter of a wealthy royalist. The union proved to be unhappy. She was a young and lively girl, little fitted to be the companion of such a serious man. They had only been married a month, when the young wife got Milton’s permission to visit her parents, and did not come back. It turned out that her relatives had agreed to her marriage to a Republican, when their party seemed to be losing power. They changed their mind when a temporary success of the Royalists revived their hopes. Milton did not see his wife for four years. During that time, he reflected much on marriage and divorce. He also wrote a treatise on divorce. In it, without mentioning his own drama, Milton regarded marriage and divorce as a social problem. An unexpected turn in the political situation of the country brought about a reconciliation of the couple, and Mary returned.

Milton kept a keen eye on the public affairs of the time. The years between 1640 and 1660 were the period of his militant revolutionary journalism. His views on civil and religious liberty served the interests of the revolutionary party, and Milton became the most prominent publicist of the Revolution.

When a Republican government was established in 1649, Milton was appointed Latin Secretary of the Council of State. He translated diplomatic papers from Latin and into Latin. He also continued writing pamphlets and treatises. In his excellent pamphlets The Tenure of Kings and Magistrates, Defence of the People of England and Image Breaker, he made Europe realize that the Revolution>

During the years of his work as Latin Secretary and journalist, Milton wrote only a few sonnets, one of them was To the Lord General Cromwell.

Milton had had poor eyesight even as a child, and now doctors warned him that unless he stopped reading and writing entirely, he would lose eyesight. To this Milton replied that he had already sacrificed poetry and was now ready to sacrifice his eyesight for the liberty of his people. He lost his sight in 1652. In the same year, his wife died in childbirth. Milton was left with three young daughters. Four years later, he married Catherine Woodcock, the daughter of a Republican this time, but that happiness did not last long. Catherine died within a year of their marriage.

The death of Cromwell in 1660 was followed by the restoration of monarchy, and Milton was discharged from his office. The work of all his lifetime was destroyed. All his famous pamphlets were burnt by the hangmen. But Milton’s spirit>

The years of Milton’s retirement became the third period in his literary career. During that period, he created the things that made him one of the greatest poets of England. These were Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained. Unfortunately, two of his daughters refused to help him in his work. Only his youngest daughter Deborah was willing to read Latin books to her blind father. With the help of a few loyal friends, Milton completed Paradise Lost in 1663.

The characters of the poem are God the Almighty, Satan, three guardian-angels and the first man and woman, Adam and Eve. This epic poem written in 12 parts is a revolt against God who autocratically rules the universe. The revolutionary spirit is shown in Satan, who revolts against God and is driven out of Heaven. Though banished from Paradise, Satan is glad to get freedom. Milton gives Satan human qualities. His Satan is determined to go on with his war against God. Milton’s Adam and Eve are not just Biblical characters, but Man and Woman who are full of energy, who love each other and who are ready to face whatever the earth has in store for them, rather than part.

The revolutionary poets of the 19th century said that Milton was the first poet who refused to accept the conventional Bible story, but turned Adam and Eve into human beings.

When Milton’s fame reached the Court of Charles II, the King’s brother (the future King James II) paid a visit to the blind poet and asked if he did not regard the loss of his eyesight as a judgment inflicted by God for what he had written against the late King Charles I. Milton replied: ‘If your Highness thinks that the calamities which befall us here are indications of the anger of God, in what manner are we to account for the fate of the King, your father? The displeasure of God must have been much greater against him than me, for I have lost my eyes, but he lost his head.’

Milton’s third wife was Elizabeth Minshel. She>

Milton’s works form a bridge between the poetry of the Renaissance and the poetry of the classicists of a later period. He was attracted by the poetry of ancient mythology and drama, like the writers and poets of the Renaissance. At the same time, he was a champion of the revolutionary cause and thought that only a Republican government could provide a foundation for freedom.

| DO YOU KNOW THAT | |

| ? |

ASSIGNMENTS (2)

I. Review the material of Section 2 and do the following test. Check yourself by the key at the end of the book.

Test 2

1. The Renaissance in England falls on the _____ century.

a. 14th; b. 15th; c. 16th; d. 17th

2. The Invincible Armada was defeated by ___

a. Francis Drake; b. Charles I; c. Admiral Nelson

3. The Fairy Queen was written by ___

a. W. Shakespeare; b. Ch. Marlowe; c. E. Spenser

4. W. Shakespeare was ____

a. an actor; b. a playwright; c. a literary critic

5. The Gunpowder plot was in ___

a. 1515; b. 1605; c. 1649

6. The Pilgrim Fathers were___

a. Catholics; b. Protestants; c. Puritans

7. The King who dismissed Parliament several times was___

a. Henry VIII; b. James I; c. Charles I

8. After the establishment of the Commonwealth, O. Cromwell was proclaimed

- King; b. Lord Protector; c. Lord Chancellor

- John Milton wrote ____

a. Paradise Lost; b. The Fairy Queen; c. Much Ado About Nothing

10. “The Father of the English Opera” was ____

a. William Byrd; b. Henry Purcell; c. John Bull

11. As a result of the Civil War, England became ____

a. a parliamentary monarchy; b. a republic; c. an absolute monarchy

12. The Great Fire of London was in _______ .

a. 1666; b. 1605; c. 1649

II. Get ready to speak on the following topics:

- Reformation in England. Henry VIII. Mary Tudor (“Bloody Mary”).

- The Elizabethan age. England’s relations with Spain. The geographical discoveries in 16th century. The development of philosophy, literature and the theatre (Thomas More, Edmund Spenser, Christopher Marlowe, William Shakespeare).

- The reign of James I: the Gunpowder plot, the Pilgrim Fathers.

- The Civil War and the Commonwealth, Oliver Cromwell. The Restoration.

- The Great Fire of London. The development of literature (John Milton), arts (William Dobson, Christopher Wren, Henry Purcell) and science (Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, Edmund Halley) in the 17th century.

3. Topics for presentations:

- The history of the English language.

- The Elizabethan age.

- Science in the 17th century England.

| | SECTION 3 | |

Britain in the New Age.

Modern Britain.

In Europe the 18th century was a turbulent age marked with revolutions, a tremendous upheaval in literature, philosophy and science all over the continent. It was the age when England gained the dominant place in the Channel and in the seas and became the world’s main market. It was the age of the Industrial Revolution which resulted in England’s economic growth. It was also the age of continental and colonial wars. The wars waged on the continent were the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713), the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). The wars for colonial expansion in India and North America went on without interruption. England’s rivals were Holland, France and Spain. The 18th century was a period of transition which saw the transfer of political power in Britain from absolute to parliamentary monarchy.

But before we turn to the 18th century we must speak about the event which laid the basis for England’s further development – the Glorious Revolution. For different reasons (mainly political and economic), many English historians consider the late 1680s as the beginning of the 18th century in the history of England.

I

1. The Glorious Revolution

n 1688, the bourgeoisie managed to bring the royal power, the armed forces and taxation under the control of Parliament. The arrangement is known as the Revolution of 1688, or the Glorious Revolution. King James II who succeeded to the throne after the death of his brother, Charles II, introduced pro-Catholic reforms and, finally, converted to Catholicism himself. All that which provoked Protestant hostility in the country. James II’s opponents sparked off the Glorious Revolution by inviting a Protestant – William, the Prince of Orange, to take the English crown. William of Orange arrived with an invasion force. In fact, William II, as he came to be known, was one of the legal heirs to the throne: he was the grandson of Charles I, and his wife Mary was James II’s daughter and Charles I’s granddaughter. King James II had to flee to France in 1689. Parliament declared that James II had abdicated and William and Mary accepted the throne. The attempts to restore James II to the throne failed in 1690.

William III proved to be an able diplomat but a reserved and unpopular monarch. In 1689, William and Mary accepted the Bill of Rights curbing royal power and granting the rights of parliament. It also restricted succession to the throne only to Protestants. The Bill of Rights laid the basis for constitutional monarchy. William and Mary ruled jointly until Mary’s death in 1694. Her husband died after a fall from his horse in 1702. The most important result of the Glorious Revolution is the transition from absolute to parliamentary monarchy. In 1707, during the reign of Queen Anne, Act of the Union created a single Parliament for England and Scotland.

2. Political and economic development of the country

The 18th century was a sound-thinking and rational age. Life was ruled by common sense. It was the proper guide to thought and conduct in commerce and industry. This period saw a remarkable rise in the fields of philosophy, natural sciences and political economy. Adam Smith (1723 – 1790), the Scottish economist, wrote his Wealth of Nations in 1776. His ideas dominated the whole of industrial Europe and America until the revival of opposing theories of state control and protection. Adam Smith was one of the founders of political economy which evolved, as a science, in the 18th century. Smith’s ideas were further developed by David Ricardo.

During the reign of George I, government power was increased because the new king spoke only German and relied on the decisions of his ministers. The most influential minister, who remained the greatest political leader of Britain for twenty years, was Robert Walpole. He is considered to have been Britain’s first Prime Minister. Moreover, it was R. Walpole who fathered the idea of using banknotes. As Britain was waging a series of costly wars with France, the government had to borrow money from different sources. In 1694, a group of financiers agreed to establish a bank if the government pledged to borrow from it alone. The new bank, called the Bank of England, had authority to raise money by printing ‘bank-notes’. But the idea>th century, money dealers had been giving people so-called ‘promissory notes’ signed by themselves. The cheques that are used today developed from those promissory notes. Walpole also promoted a parliamentary act, which obliged companies to bear responsibility to the public for the money, which they borrowed by the sales of shares.

In politics, Walpole was determined to keep the Crown under a firm parliamentary control. He realized that with the new German monarchy that was more possible than ever before. Walpole stressed the idea that government ministers should work together in a small group called the Cabinet. He insisted that all Cabinet ministers should bear collective responsibility for their decisions. If any minister disagreed with a Cabinet decision, he was expected to resign. The rule is still observed today. Walpole opposed wars, and increased taxes on objects of luxury including tea, coffee and chocolate.

R. Walpole’s most influential enemy was William Pitt who stressed the importance of developing trade and strengthening Britain’s position overseas even by armed force. His policies lead to a number of wars with France. In the war of 1756, Pitt declared that the target was French trade which was to be taken over by Britain. In Canada, the British army took Quebec, which gave Britain control over fish, fur and timber trades. The French army was also defeated in India and a lot of Britons went to India to make their fortunes. Britain became the most powerful country in the world. British pride was expressed in a national song written in 1742, Rule, Britannia.

3. Life in town

At the beginning of the 18th century, England was becoming the main commercial centre of Europe. In 1700 England and Wales had a population of about 5.5 million people. By the end of the century it reached 8.8. million. Including Ireland and Scotland, the total population was about 13 million people.

England was still a country of small villages. The big cities of the future were only beginning to emerge. After London, the second largest city was Bristol. Its rapid growth and importance was based on the triangular trade: British-made goods were shipped to West Africa, West African slaves were transported to the New World, and American sugar, cotton and tobacco were brought to Britain.

By the middle of the century Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield and Leeds were already big cities. But administratively and politically, they were still treated as villages and had no representation in Parliament.

All towns, old and new, had no drainage system; dirt was seldom or never removed from the streets. Towns often suffered from epidemics. In London, only one child in four grew up to become an adult. The majority of the poorer population suffered from drinking as the most popular drink was gin. Quakers started developing the beer industry and promoting the spread of beer as a less damaging drink. Soon beer drinking became a national habit.

A

4. London and Londoners

s England was becoming the main commercial centre of Europe, London was turning into the centre of wealth and civilization. Ships came up the Thames which resembled a forest of masts. There was a great deal of buying, selling and bargaining in the open.

The City, or the Square Mile of Money, became the most important district of London. The Lord Mayor was never seen in public except in his rich robe, a hood of black velvet and a golden chain. He was always escorted by heralds and guards. On great occasions, he appeared on horseback or in his gilded coach. A commonly used phrase said, “He who is tired of London is tired of life”. But the 18th century London was, naturally, different from what it became later. The streets were so narrow that wheeled carriages had difficulty in passing each other. Houses were built of brick or stone, as well as of wood and plaster. The upper part of the houses was built much further out than the lower part, so far out that people living on the upper floors could touch each other’s hands by stretching out over the street. Houses were not numbered as the majority of the population were illiterate. Shops, inns, taverns, theatres and coffee-houses had painted signs illustrating their names. The most typical names and pictures were “The Red Lion”, “The Swan”, “The Golden Lamb”, “The Blue Bear”, “The Rose”.

Londoners preferred to walk in the middle of the streets so as to avoid the rubbish thrown out of the windows and open doors. In rainy weather the gutters that ran along the streets, turned into black torrents, which roared down to the Thames, carrying to it all the rubbish from the City. The streets were not lighted at night. Thieves and pickpockets plied their trade without fear of being punished. It was difficult to get about even during the day, let alone at night.

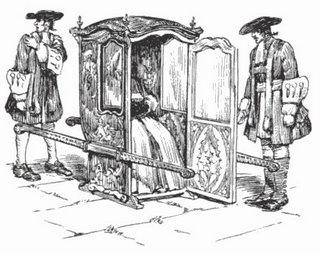

Wealthier Londoners preferred using the river. The boatmen dressed in blue garments waited for customers at the head of the steps leading down to the waterside. Another way of getting about London

was in a sedan-chair. It was put on two long horizontal poles which were carried by two men. When ladies went out to pay visits, the lid of the sedan-chair had to be opened to make room for the fashionable hair-dresses and hats.

was in a sedan-chair. It was put on two long horizontal poles which were carried by two men. When ladies went out to pay visits, the lid of the sedan-chair had to be opened to make room for the fashionable hair-dresses and hats.The introduction of coffee, tea and chocolate as common drinks led to the establishment of coffee-houses. These were a kind of first clubs. Coffee-houses kept copies of newspapers, they became centres of political discussion. Every coffee-house had its own favourite speaker to whom the visitors listened with great admiration. Each rank and profession, each shade of religious or political opinion had its own coffee-house. There were earls and clergymen, university students and translators, printers and art-makers. Men of literature and the wits met at a coffee-house which was frequently visited by the poet John Dryden. Here one could also meet Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Johnson and other celebrities.

5. The Industrial Revolution

The 18th century gave birth to the Industrial Revolution: it brought about the mechanization of industry and the consequent changes in social and economic organization. The change from domestic industry to the factory system began in the textile industry. It was transformed by such inventions as Kay’s flying shuttle (1733), Hargreave’s spinning jenny (1764) and others. Newcomen’s steam engine (1705) perfected by Watt (1765) provided a power supply. Communications were improved by the locomotives invented by Stephenson. The 18th century improvements in agricultural methods freed rural labour for industry and increased the productivity of the land. That was followed by the rapid growth of towns, mostly near coal-fields. Miserable working and housing conditions later inspired the Luddites, or workers who deliberately smashed machinery in the industrial centres in the early 19th century. The followers of Ned Ludd, an 18th century riot leader, believed that the use of machines caused unemployment. They fought against unemployment in a most primitive way which, to them, seemed effective.

The 18th century gave birth to the Industrial Revolution: it brought about the mechanization of industry and the consequent changes in social and economic organization. The change from domestic industry to the factory system began in the textile industry. It was transformed by such inventions as Kay’s flying shuttle (1733), Hargreave’s spinning jenny (1764) and others. Newcomen’s steam engine (1705) perfected by Watt (1765) provided a power supply. Communications were improved by the locomotives invented by Stephenson. The 18th century improvements in agricultural methods freed rural labour for industry and increased the productivity of the land. That was followed by the rapid growth of towns, mostly near coal-fields. Miserable working and housing conditions later inspired the Luddites, or workers who deliberately smashed machinery in the industrial centres in the early 19th century. The followers of Ned Ludd, an 18th century riot leader, believed that the use of machines caused unemployment. They fought against unemployment in a most primitive way which, to them, seemed effective. 6. The Colonial Wars

At the end of the 18th century the struggle of the 13 American colonies for independence from British rule turned into the War of American Independence (1775 – 1783). The war was caused by the British attempts to tax the colonies for revenue and to make them pay for a standing army. The colonies revolted under George Washington and declared their independence in 177. In 1778 – 1780 France, Spain and the Netherlands, one by one, declared war on Britain. Military operations were held on the American continent. In 1781 Britain lost command of the sea, and her army was finally defeated at Yorktown. In 1783 the war ended with the Treaty of Paris, in which the independence of the USA was officially recognized. George Washington became the country’s first president. The war discredited the government of George III, weakened France financially, and served as an inspiration for the French Revolution and for revolutions in the Spanish colonies in America.

It should be noted that the War of Independence was won by the Americans largely due to the French support. The famous poet and playwright Bomarchet, who was a secret agent of the French government, shipped arms and ammunition over the Atlantic Ocean to the insurgents. In Paris, he met Benjamin Franklin, who was the American ambassador to France. Franklin is one of the prominent figures in American history. To begin with, he helped to draft the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Besides being one of the founding fathers of the American nation, Franklin gained a worldwide reputation for his scientific discoveries, which included a new theory of the nature of electricity, and for his inventions, among which there was the lightning conductor.

-

7. The Development of arts