Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture across History Учебное пособие

| Вид материала | Учебное пособие |

- Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture, 365.14kb.

- Курс лекций по дисциплине английский язык Факультет: социальный, 440.82kb.

- Учебное пособие соответствует государственному стандарту направления «Английский язык», 2253.16kb.

- Lesson one text: a glimpse of London. Grammar, 3079.18kb.

- Реферат по дисциплине: страноведение на тему: «The geographical location of the United, 1698.81kb.

- Education in great britain, 98.44kb.

- The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 257.28kb.

- Г. В. Плеханова английский язык учебно-методическое пособие, 1565.3kb.

- А. Л. Пумпянский написал серию из трех книг по переводу, 3583.47kb.

- Учебное пособие для студентов факультета иностранных языков / Сост. Н. В. Дороднева,, 393.39kb.

| | Е.В. Воевода АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК Великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture across History Учебное пособие для студентов II курса факультета МЭО  |

МОСКОВСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ ИНСТИТУТ

МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЙ (УНИВЕРСИТЕТ) МИД РОССИИ

Кафедра английского языка № 2

Е.В. Воевода

АНГЛИЙСКИЙ ЯЗЫК

Великобритания:

история и культура

Great Britain: Culture across History

Учебное пособие

для студентов II курса

факультета МЭО

Издательство

«МГИМО-Университет»

2009

ББК 81.2Англ

В63

| В63 | Воевода Е.В. Великобритания: история и культура = Great Britain: Culture across History : учеб. пособие по англ. яз. для студентов II курса фак-та МЭО / Е.В. Воевода. Моск. гос. ин-т междунар. отношений (ун-т) МИД России, каф. англ. яз. № 2. — М. : МГИМО-Университет, 2009. — 223 с. ISBN 978-5-9228-0540-7 Настоящее учебное пособие по страноведению Великобритании адресовано студентам факультета МЭО МГИМО(У) МИД России, обучающихся по программе II курса бакалавриата и изучающих английский язык как основной иностранный. Пособие призвано расширить и углубить фоновые знания студентов экономического профиля в области истории и культуры страны изучаемого языка, освещая историко-экономические события, происшедшие на Британских островах, зарождение и развитие английского языка и особенности английской культуры: литературы, музыки, архитектуры, живописи. |

ББК 81.2Англ

ISBN 978-5-9228-0540-7 © Московский государственный институт

международных отношений (университет)

МИД России, 2009

© Воевода Е.В., 2009

CONTENTS

| | | Page |

| Предисловие …………………………………………………………… | 4 | |

| Методическая записка ……………………………………………….. | 5 | |

| SECTION 1 | Britain in ancient times. England in the Middle Ages …………………………………………….. | 7 |

| CHAPTER 1. The British Isles before the Norman Conquest. ………………………………………………... | 7 | |

| CHAPTER 2. The Norman Conquest of Britain. ….......... | 35 | |

| CHAPTER 3. England in the late Middle Ages. ………... | 54 | |

| ASSIGNMENTS. ………………………………….......... | 74 | |

| SECTION 2 | The English Renaissance …………………………….. | 77 |

| | CHAPTER 4. The Tudor age. ……………….......... | 77 |

| CHAPTER 5. The development of drama and the theatre in Elizabethan England……………………...………….. | 98 | |

| CHAPTER 6. Stuart England. …………………………... | 113 | |

| ASSIGNMENTS. ………………………………….......... | 130 | |

| SECTION 3 | Britain in the New Age. Modern Britain ……………. | 132 |

| | CHAPTER 7. Britain in the 18th century ………….......... | 132 |

| CHAPTER 8. From Napoleonic wars to Victorian Britain. ………………………………………......... | 150 | |

| CHAPTER 9. Britain in the 20th century. …………….. | 167 | |

| ASSIGNMENTS. ………………………………….......... | 189 | |

| GLOSSARY. ……………………………………………………………. | 191 | |

| CROSS-CULTURAL NOTES. ………………………………………… | 202 | |

| Key to Tests | …………………………………………………………… | 219 |

| References | …………………………………………………………… | 220 |

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Учебное пособие по страноведению Великобритании “Great Britain: Culture Across History” адресовано студентам II курса факультета МЭО (1 семестр), изучающих английский язык как основной иностранный (уровень B1) по следующим направлениям подготовки: «Экономика», «Международные финансы и кредит». «Коммерция». Пособие соответствует программе подготовки бакалавров по дисциплине «Иностранный язык» и применяется в лекционно-семинарском курсе в сочетании с мультимедийной программой «История и культура Великобритании» (авторы: Е.В. Воевода, Т.В. Сильченко, А.А. Артемов), разработанной в МГИМО.

Пособие состоит из трех блоков (Sections), включающих девять глав (Chapters). Каждая глава рассчитана на одну неделю изучения после прослушивания аудиторной лекции и работы с мультимедийной программой. Каждая глава завершается разделом «Знаете ли вы, что…?», предлагающим информацию, способствующую расширению кругозора студентов.

После изучения каждого блока предлагается тест на контроль усвоения фактического материала, который студенты могут проверить по ключу, вопросы для обсуждения на семинарских занятиях и темы для студенческих презентаций. В пособии также дается глоссарий и лингвострановедческий комментарий к каждой главе.

При написании пособия использовались текстовые отрывки и карты из опубликованных работ, приведенных в разделе “References” в качестве иллюстраций (в широком смысле) в объеме, оправданном поставленной целью пособия и методикой, в соответствии с Законом Российской Федерации об авторском праве от 9 июля 1993 г. № 5351-1.

МЕТОДИЧЕСКАЯ ЗАПИСКА

В настоящее время профессиональные требования к владению иностранным языком для выпускника факультета международных экономических отношений не могут быть сведены лишь к овладению речевыми навыками в рамках языка специальности. Успешное сотрудничество с зарубежными партнерами предполагает знание и оперирование такими понятиями, которые отражают видение мира и национальную культуру представителя того или иного народа. Поэтому при обучении иностранным языкам необходимым элементом является обучение культурологическому аспекту.

Предлагаемая автором методика изучения страноведческого материала о стране изучаемого языка содействуют развитию компетентностей, связанных с коммуникацией, творческим и критическим анализом, независимым мышлением и коллективным трудом в поликультурном контексте, когда творчество основывается на сочетании традиционных знаний и навыков с современными информационными технологиями.

Весь предлагаемый материал разбит на три крупных блока (Sections), каждый из которых включает аудиторную интерактивную лекцию, сопровождаемую мультимедийной программой. После прослушивания лекции студентам рекомендуется ознакомиться с более полной версией материала по теме в предлагаемом пособии, изучить лингвострановедческий комментарий и ознакомиться с незнакомыми словами в глоссарии.

Повторяемость лексики в каждом блоке, употребление новых лексических единиц в тексте, в лекциях, заданиях и тестах, при подготовке к семинарским занятиям и докладам способствует усвоению студентами богатого рецептивного словаря, что предусмотрено кафедральной программой по английскому языку.

После каждых трех лекций проводятся два семинарских занятия, вопросы к которым даны в заданиях (assignments 1-3). Задания включают в себя образцы тестов по изученной тематике (с ключами), вопросы к семинарским занятиям и темы для презентаций. После первичного контроля (выполнения тестовых заданий) студенты переходят к составлению собственных сообщений по предложенной теме. Окончательный контроль усвоения материала осуществляется преподавателем в аудитории в форме дискуссии, проверки устных докладов или письменных сообщений (в отдельных случаях) и студенческих коллективных презентациях.

Студенты делятся на «команды» (teams), включающие трех-четырех докладчиков и такое же количество оппонентов. Задача докладчиков – используя основной материал учебного пособия и дополнительно найденный материал по теме, так организовать его презентацию, чтобы она была интересна аудитории, чтобы в ней участвовали все три докладчика, чтобы она сопровождалась собственной мультимедийной программой в Power Point. Задача оппонентов – подготовить вопросы докладчикам с целью получения дополнительной или уточняющей информации, если возможно – оспорить какие-то положения презентации, представив свои аргументы. Как и докладчики, оппоненты готовятся и выступают сообща, развивая умение работать в команде. Семинары позволяют глубже обсудить изучаемый материал, в том числе использовать информацию, самостоятельно найденную студентами.

Презентации, подготовленные студентами, – это новая и перспективная форма семинарской работы, развивающая навык социального общения.

Работа с пособием способствует развитию у студентов аналитической, коммуникативной, лингвострановедческой компетенций, являющихся профессионально значимыми для будущего экономиста-международника.

Автор

| | SECTION 1 | |

Britain in ancient times.

England in the Middle Ages.

- T

1. The Earliest Settlers

he Iberians

About 3 thousand years before our era the land we now call Britain was not separated from the continent by the English Channel and the North Sea. The Thames was a tributary of the Rhine. The snow did not melt on the mountains of Wales, Cumberland and Yorkshire even in summer. It lay there for centuries and formed rivers of ice called glaciers, that slowly flowed into the valleys below, some reaching as far as the Thames. At the end of the ice age the climate became warmer and the ice caps melted, flooding the lower-lying land that now lies under the North Sea and the English Channel. Many parts of Europe, including the present-day British Isles, were inhabited by the people who came to be known as the Iberians. Some of their descendants are still found in the North of Spain, populating the Iberian peninsular. Although little is known about the Iberians of the Stone Age, it is understood that they were a small, dark, long-headed race that settled especially on the chalk downs radiating from Salisbury Plain. All that is known about them comes from archaeological findings – the remains of their dwellings, their skeletons as well as some stone tools and weapons. The Iberians knew the art of grinding and polishing stone.

On the downs and along the oldest historic roads, the Icknield Way and the Pilgrim’s Way, lie long barrows, the great earthenworks which were burial places and prove the existence of marked class divisions. Other relics of the past are the stone circles of Stonehenge and Avebury on Salisbury Plain. Avebury is the grandest site while Stonehenge is the best known. The name of the place comes from the Saxon word Stanhengist, or “hanging stones”. Stonehenge is fifteen hundred years older than the Egyptian pyramids. It is made of stone gates standing in groups of twos. Each vertical stone weighs fifty tons or more. The flat stones joining the gates weigh 7 tons. Nobody knows why that huge double circle was build, or how primitive people managed to move such heavy stones. Some researchers think that it was built by the ancient Druids who performed their rites in Stonehenge. Others believe that it was built by the sun-worshippers who came to this distant land from the Mediterranean when the Channel was a dry valley on the Continent. Stonehenge might also have been an enormous calendar. Its changing shadows probably indicated the cycle of the seasons and told the people when it was time to sow their crops.

People and crops have vanished, but the stones stand fast and stubbornly keep their secrets from us.

- The Celts

The period from the 6th to the 3rd century BC saw the migration of the people called the Celts. They spread across Europe from the East to the West and occupied the territory of the present-day France, Belgium, Denmark, Holland and Great Britain. (See Map 1.)

The Celtic tribes that crossed the Channel and landed on the British Isles were the Britons, the Scots, the Picts and the Gauls. The Britons populated the South, the Picts moved to the North, the Scots went to Ireland and the rest settled in between. Later, the Scots returned to the main island and in such numbers that the northern part of it got the name of Scotland. The history of the Picts and their struggle with the Scots was beautifully described by R.L. Stevenson in the ballad Heather Ale.

Map 1

( From S.D. Zaitseva. Early Britain. Moscow, 1975.)

In reality, the Picts were not exterminated but assimilated with the Scots. As for the Iberians, some of them were slain in battle, others were driven westwards into the mountains of Wales, the rest assimilated with the Celts. The last wave of the Celts were the Belgic tribes which arrived about 100 BC and occupied the south-east of the main island.

The Celts are known from the Travelling Notes by Pytheus, a traveller from Massilia (now – Marseilles). He visited the British Isles in the 4th century BC. Later, Herodotus wrote that even in the 5th century BC Phoenicians came to the British Isles for tin, which was used for making bronze. The British Isles were then called the Tin Islands.

Another person whom we owe reminiscences about early Britain is Guy Julius Caesar. In 55 BC his troops first landed in Britain. According to Caesar’s “Commentaries on the Gallic War,” the Celts, against whom he fought, were tall and blue-eyed people. Men had long moustaches (but no beards) and wore shirts, knee-long trousers and striped or checked cloaks which they fastened with a pin. (Later, their Scottish descendants developed it into tartan.) Both men and women were obsessed with the idea of cleanliness and neatness. As is known from reminiscences of the Romans, “neither man nor woman, however poor, was seen either ragged or dirty”.

Economically and socially the Celts were a tribal society made up of clans and tribes. The Celtic tribes were ruled by chiefs. The military leaders of the largest tribes were sometimes called kings. In wartime the Celts wore skins and painted their faces blue to make themselves look more fierce. They were armed with swords and spears and used war chariots in fighting. Women seem to have had extensive rights and independence and shared responsibility in defending their tribesmen. It is known that when the Romans invaded Britain, two of the largest tribes were ruled by women.

The Celts were pagans and their priests, the Druids, who were important members of the ruling class, preserved the tribal laws, religious teachings, history, medicine and other knowledge necessary in Celtic society. They worshipped in sacred places (on hills, by rivers, in groves of trees) and their rites sometimes included human sacrifice.

The Celts lived in villages and practised a primitive agriculture: they used light ploughs and grew their crops in small square fields. They knew the use of copper, tin, and iron, kept large herds of cattle and sheep which formed their chief wealth.

The Celts traded both inside and beyond Britain. On the Continent, the Celtic tribes of Britain carried on trade with Celtic Gaul. Trade was also an important political and social factor in relationship between tribes. Most trade was conducted by sea or river. It is no accident that the capitals of England and Scotland appeared on the river banks, in place of the old trade routes. The settlement on the Thames, which existed before London, was a major trade outpost eastwards to Europe.

The descendants of the ancient Celts live on the British Isles up to this day. They are the Welsh, the Scottish and the Irish. The Welsh language, which belongs to the Celtic group, is the oldest living language in Europe. In the Highlands of Scotland, as well as in the western parts of Ireland, there is still a strong influence of the Celtic language. Some words of the Celtic origin still exist in Modern English. Scholars believe that about a dozen common nouns are of the Celtic origin; among these are cradle, bannock, cart, down, loch (dial.), coomb (dial.), mattock. Most others are geographical names. These are the names of Celtic settlements which later grew into towns: London, Leeds and Kent which got its name after the name of a Celtic tribe. There are several rivers in England which still bear Celtic names: Avon and Evan, Thames, Severn, Mersey, Derwent, Ouse, Exe, Esk, Usk. The Celtic word loch is still used in Scotland to denote a lake: Loch Ness, Loch Lomond.

Celtic borrowings in English

| Modern English | Celtic | meaning |

| Avon, Evan | amhiun | river |

| Ouse, Exe, Esk, Usk | uisge | water |

| Dundee, Dumbarton, Dunscore; the Downs | dun | hill; bare, open highland |

| Kilbrook | coill | wood |

| Batcombe, Duncombe | comb | deep valley |

| Ben-Nevis, Ben-More | bein | mountain |

F

2. Roman Britain

or almost four centuries Britons were ruled by the Romans, who called their country Britanni or Britannia. It was the most westerly and northerly province of the Roman empire. The Romans, led by Julius Caesar, came to the British Isles in BC 55 and a year later returned to the Continent as the Celtic opposition was strong. In BC 54 he returned with 25,000 men. The Romans crossed the Thames and stormed the Celtic capital of Cassivellaunus. Caesar then departed, taking hostages and securing a promise to pay tribute.

In the ninety years between the first two raids and the invasion of the Romans in AD 43, a thorough economic development in South-East Britain went on. Traders and colonists settled in large numbers and the growth of towns was so considerable that in AD 50, only seven years after the invasion of Claudius, Verulamium (now St. Albans) was granted the full status of a Roman town (municipium) with self-government and the rights of Roman citizenship for its inhabitants.

It would be wrong to assume that the Celts eagerly surrendered to the invaders. The hilly districts in the West were very difficult to subdue, and the Romans had to set up many camps in that part of the country and station their legions all over Britain to defend the province.

The Celts fought fiercely against the Romans who never managed to become masters of the whole island. In AD 61-62 Queen Boadicea (Boadica) led her tribesmen against the Romans. Upon her husband’s death, she managed to raise an army which raided the occupied territories slaying the Romans and their supporters, burning down and ruining the Roman towns and nearly bringing an end to the Roman rule of Britain as such. It was only when she was captured by the Roman soldiers and took poison that peace was restored in the province.

The Romans were also unable to conquer the Scottish Highlands, or Caledonia as they called it, thus the province of Britain covered only the southern part of the island. From time to time the Picts from the North managed to raid the Roman part of the island, burn their villages, and drive off their cattle and sheep. During the reign of the Emperor Hadrian a high wall was built in the North to defend the province from the raids of the Picts and the Scots. (See Map 2.) The wall, known as Hadrian’s Wall, stretches from the eastern to the western coast of the island. With its forts, built a mile apart one from another, the wall served as a stronghold in the North. At the same time, when the Northern Britons were not at war with the Romans, the wall turned into an improvised market place for either party.

In AD 139 – 42 the Emperor Antoninus Pius abandoned Hadrian’s Wall and constructed a new frontier defence system between the Forth and the Clyde – the Antonine Wall – but its use was short-lived and Hadrian’s Wall was again the main northern frontier by AD 164.

One of the greatest achievements of the Roman Empire was its system of roads, in Britain no less than elsewhere. When the legions arrived in Britain in the first century AD, their first task was to build a system of roads. Stone bridges were built across rivers. Roman roads were made of of stones, lime and gravel. They were vital not only for the speedy movement of troops and supplies from one strategic center to another, but also allowed the movement of agricultural products from farm to market.

Map 2

( From S.D. Zaitseva. Early Britain. Moscow, 1975.)

Within a generation the British landscape changed considerably. London became the chief administrative centre. From it, roads spread out to all parts of the province. Some of the roads exist up to this day, for example Watling Street which stretched from Dover to London, then to Chester and into the mountains of Wales. Unlike the Celts, who lived in villages, the Romans were city-dwellers. The Roman army built legionary fortresses, forts, camps, and roads, and assisted with the construction of buildings in towns. The Romans built most towns to a standardized pattern of straight, parallel main streets that crossed at right angles. The forum (market place) formed the centre of each town. Shops and such public buildings as the basilica, baths, law-courts, and temple surrounded the forum. The paved streets had drainage systems, and fresh water was piped to many buildings. Houses were built of wood or narrow bricks and had tiled roofs.

The chief towns were Colchester, Gloucester, York, Lincoln, Dover, Bath and London (or Londinium). It is common knowledge that London was founded by the Romans in place of an earlier settlement.

Roman towns fell into one of three main types: coloniae, municipia and civitates. The coloniae of Roman Britain were Colchester, Lincoln, Gloucester, York, and possibly London, and their inhabitants were Roman citizens. The only certain municipia was Verulamium (St. Albans), a self-governing community with certain legal privileges. The civitates, towns of non-citizens, included most of Britain’s administrative centres.

The Romans also brought their style of architecture to the countryside in the form of villas. Some very large early villas are known in Kent and in Sussex.

Both public buildings and private dwellings were decorated in imitation of the Roman style. Sculpture and wall painting were both novelties in Roman Britain. Statues or busts in bronze or marble were imported from Mediterranean workshops, but British sculptures soon learned their trade and produced attractive works of their own. Mosaic floors, found in towns and villas, were at first laid by imported craftsmen. But there is evidence that by the middle of the 2nd century a local firm was at work at Colchester and Verulamium, and in the 4th century a number of local mosaic workshops can be recognized by their styles.

When Christianity gained popularity in the Empire, it also spread to the provinces and was established in Britain in the 300s. The first English martyr was St. Alban who died about 287.

In 306, Constantine the Great, the son of Constantine Chlora and Elene (Helen), the daughter of a British chief, became the Roman Emperor. He stopped the persecution of Christians and became a Christian himself. All Christian churches were centralised in Constantinople which was made the capital of the Empire. This religion came to be known as the Catholic Church. (‘catholic’ means ‘universal’.) Greek and Latin became the languages of the Church all over Europe including Britain.

Literary evidence suggests that Britons adopted Latinized names and that the elite spoke and wrote Latin. The largest number of Latin words was introduced as a result of the spread of Christianity: abbot, altar, angel, creed, hymn, idol, organ, nun, pope, temple and many others. The traces of Latin are still found in modern English:

Latin borrowings in English

| Modern English | Latin | meaning |

| Chester, Doncaster, Gloucester | castra | camp |

| street, Stratford | strata via | a paved road |

| wall | vallum | a wall of fortifications |

| Lincoln, Colchester | colonia | colony |

| Devonport | portus | port, haven |

| Norwich, Woolwich | vicus | village |

| Chepstow; Chapman | caupo | a small tradesman |

| pound | (pondo) pondus | (measure of) weight |

| mile | millia passum | 1000 steps |

| piper | pepper | перец |

| wine | vinum | вино |

| butter | butyrum | масло |

| cheese | caseus | сыр |

| pear | pirum | груша |

| mill | molinum | мельница |

Despite the growth of towns and all the other essentials of civilization that came with the Roman conquest, the standards of living changed little. Britain was an agricultural province, dependent on small farms. Peasants still built round Celtic huts and worked in the fields in the same way. Despite the 400 years of Roman influence, Britain was still largely a Celtic society.

The conquest of Britain by the Roman Empire lasted up to the beginning of the 5th century. In 410 the Roman legions were called back to Rome, and those that stayed behind were to become the Romanized Celts (Britons) who faced the invasion of the barbarians – the Germanic tribes of Angles and Saxons.

- T

3. The Anglo-Saxon period

he Invasion

Germanic tribes had raided the British shores long before the withdrawal of the Roman legions. But the 5th century became the age of increased Germanic expansion and by the end of the century several West Germanic tribes had settled in Britain. The first invaders, in fact, came at the request of a British king who needed their assistance in a local war. The newcomers soon overran their hosts, and other Germanic tribes followed them in families and clans. At first they only came to plunder: drive off the cattle, seize the stores of corn and be off again to sea before the Celts could attack them. But as time went by they would come in larger numbers, and begin to conquer the country.

First came the Jutes, and then the Angles and the Saxons. (See Map 3.) The latter came from the territory lying between the Rhine and the Elbe rivers which was later called Saxony. The Jutes and the Angles came from the Jutland Peninsular. The beginning of the conquest was in 449 when the Jutes landed in Kent. Eventually, Britain held out longer than the other provinces of the Roman Empire.

Map 3

( From David MacDowell. An Illustrated History of Britain, Longman.)

It was only at the beginning of the 7th century that the invaders managed to conquer the greater part of the land. The Angles settled down to the north of the Thames, the Saxons – to the south of the Thames, the Jutes spread in the extreme south-east – the Kent Peninsular and the Isle of White.

The pagan tribes did not spare their enemies. The Celtic historian Gildas described the Anglo-Saxon invasion as ‘the ruin of Britain’. The invaders lived in villages and soon destroyed or neglected the Roman roads, villas, baths and towns. London, which had been the main trading centre, saw its decline. The invaders killed or enslaved Britons, most of the British Christians were put to death, and others took refuge in the distant parts of the country where they lived as hermits or in groups of brethren.

After a century and a half of resistance, the Celts were driven off to Wales and Cornwall, as well as to the northern part of Scotland, where they later founded independent states and spoke their native language. The Anglo-Saxons called the northern part of the country weallas (Wales) meaning ‘the land of foreigners’ and the Celts were called welsh which meant ‘foreign’. The Celts of Ireland also remained independent. Some of the Celtic tribes crossed the Channel and settled down on the French coast giving it the name of Brittany.

- Political and economic development

The period covering the 5th – 11th centuries saw transition from the tribal and slave-owning system to feudalism.

By the beginning of the 7th century, 7 kingdoms had been formed on the conquered territory which later came to be known as England. These were Kent, Sussex, Wessex, Essex (the lands of the South, West and East Saxons), Northumbria (the land that lay to the north of the river Humber, hence the name North-Humbrian), Mercia and East Anglia. (See Map 3.) The kingdoms were constantly at war for the supreme power in the country. At the beginning of the 7th century Northumbria, Mercia and Wessex dominated the other four kingdoms.

In the 8th century Mercia developed important diplomatic and commercial ties with the Continent. King Offa of Mercia became powerful enough to claim ‘kingship of English’. He managed to make a huge dyke along the border with Wales to protect his kingdom from the Celtic raids. Parts of this earth wall still exists and is known as Offa’s Dyke. After Offa’s death, though, Mercia lost its supremacy.

Social changes in the Anglo-Saxon society took a long time to come. It is recognised that the Anglo-Saxons were far less civilized than the Romans, yet they had their own institutions. Anglo-Saxon kings were elected by the members of the Witan, the Council of Chieftains, and in their decisions were advised by the councillors, the great men of the kingdom. In return for the support of his subjects who paid taxes and gave him free labour and military service, the king granted them land and protection.

Originally, all Saxon men had been warriors. From the very beginning English society had military aristocracy, or thanes. The rest of the population were peasants who cultivated the land. The division of labour led to a class division: thanes got more land and privileges from the king, and became lords, while peasants took an inferior social position and finally turned into serfs.

The basic economic unit was the feudal manor which grew its own food and carried on some small industries to cover its needs. The lord of the manor administered justice and collected taxes. It was also his duty to protect the farm and its produce. The word ‘lord’ meant ‘loaf ward, or bread keeper’ and the word ‘lady’ meant ‘loaf kneader, or bread maker’.

In agriculture, the Anglo-Saxons introduced the heavy plough which made it possible to cultivate heavier soils. All the farmland of the village was divided into two fields. When one field was used for planting crops, the other was given a ‘rest’ for a year so as not to exhaust the land. After harvest time, both would be used as pasture land. That is known as the two-field system. The Saxon methods of farming remained largely the same for many centuries to come, until the 18th century.

- Christianity in England

By the end of the 6th century England had become Christian due to the energy of the Christian missionaries from Ireland and the efforts of Pope Gregory who decided to spread his influence over England. The Roman mission headed by the monk Augustine (‘St. Augustine’s mission’) landed in Kent in 597 and built the first church in the capital town of Canterbury. Augustine became the first Archbishop of Canterbury in 601. Ever since that time, Canterbury has been the religious centre of major importance in Britain.

Later, Christianity spread over to Northumbria where there were still some traces of the influence of the first Celtic Christians. Soon the Roman Church prevailed over the Celtic Church. The Church established monasteries, or minsters (Yorkminster, Westminster), which became centres of learning and education. It was there that men could be educated and trained both for theological and civil studies. The unified organisation of the Church was an important factor in the centralisation of the country.

With the arrival of St. Augustine and his forty monks, England resumed direct contact with the life and thought of the Continent, especially its Mediterranean part. Benedict Biscop, founder of Jarrow monastery (Northumbria), on several occasions brought manuscripts from Rome, and his pupil, the Venerable Bede (?673-735), had access to all the sources of knowledge brought from continental Europe. Bede was a prominent religious and public figure of the period, who contributed to the development of English history and law. He is considered to be the first English historian. He is the author of Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People) dated 731, which was the only book on Anglo-Saxon history of the time. It is the source of almost all information on the history of England before 731.

The Church enhanced the status of kings. At the time when the eldest son of a king did not automatically inherit the throne, it was the Witan that chose the next king. Evidently, it was important for the king to obtain the support of the Church and arrange for his chosen successor to be crowned at a Christian ceremony led by a bishop. If a bishop supported the king, royal power was hard to be questioned. In their turn, kings rendered support to the Church. The first baptised Anglo-Saxon king, Aethelberht I, recognized the right to church shelter in his Code of Laws in 600.

In a way, the Church contributed to the economic development of the country. Villages and towns that appeared around monasteries increased local trade. The monks and bishops who were invited to England, came from the biggest monasteries of the Frankish lands (France and Germany) which lay on Europe’s main trade routes. They used Latin, which spread in England as the official language of the church and official documents, and that encouraged closer contact with Continental countries. England exported cheese, hunting dogs, wool and metal goods. It imported pepper, jewelry, wine, and wheel-made pottery.

The second wave of Christianity brought into the language such loan-words as arithmetic, mathematics, theatre, geography, school, paper, candle.

- Anglo-Saxon culture

The development of Anglo-Saxon culture is inseparable from the development of Christianity in England.

During the time of Pope Gregory there appeared a new form of plainsong which came from Europe and was called Gregorian chant. Gregorian chant remained the musical symbol from the 6th to the 9th centuries.

In architecture, there developed a new style in church building. One of the most completely preserved Saxon churches in England is St. Laurence in Bradford-on-Avon, built probably between the 7th and the 10th centuries. With its thick walls, narrow rounded arches and small windows it represents typical Anglo-Saxon church architecture.

The monasteries of Northumbria possessed rich collections of manuscript books which were brightly illuminated, bound in gold and ornamented with precious stones. One of the best known manuscripts of the period is St. Luke’s Gospel made at the Northumbrian island of Lindisfarne in about 698.

The first Anglo-Saxon writers and poets imitated Latin books about the early Christians. Although it was customary to write in Latin, in the 7th century there appeared a poet who composed in English. Caedmon, a shepherd from Whitby, a famous abbey in Yorkshire, composed in English for mere want of learning. One of the few recorded pieces of Caedmon’s poetry is a nine-line hymn, an English fragment in Bede’s History. It may be considered as the first piece of Christian literature to appear in Anglo-Saxon England. The hymn is especially notable because, according to the Venerable Bede, it was divinely inspired. Much of Old English poetry was intended to be chanted or sung by scops, or bards. One night, at a feast, when each of the guests was asked to sing a song, Caedmon quietly stole out and lay down in the cow-shed, ashamed that he had no gift of singing. In his sleep he heard a voice telling him to stand up and sing the Song of Creation. Caedmon obeyed the mysterious voice and sang the verses he had never heard before. When he woke up, he returned to the guests and sang the song to them. That made him so famous that Caedmon was invited to the abbey where he spent the rest of his life composing religious poetry. Almost all this poetry was composed without rhyme, in a characteristic line of four stressed syllables alternating with a number of unstressed ones.

Old English poetry was mainly restricted to three subjects: religious, heroic and lyrical. The greatest heroic poem of the Anglo-Saxon period was Beowulf, an epic poem written down in the 10th but dating back to the 7th or 8th century. It is valuable both from the linguistic and the artistic point of view. Beowulf is the oldest poem in Germanic literature. Although Beowulf is essentially a warrior’s story, it serves as a source of information about the customs and ways of the ancient Jutes, their society and their feasts and amusements.

The poem consists of several songs arranged in three chapters and numbers over 3,000 lines. It is based on the legends of Germanic tribes and describes the adventures and battles of legendary heroes who had lived long before the Anglo-Saxons came to Britain. The scene is set among the Jutes and the Danes. The poem describes the struggle of a Scandinavian hero, Beowulf, who destroyed the monster Grendel, Grendel’s evil mother and a fire-breathing dragon. The extraordinary artistry with which fragments of other Scandinavian sagas are incorporated in the poem and with which the plot is made symmetrical has only recently been fully recognised.

- Formation of the English language

As a result of the conquest, the Anglo-Saxons made up the majority of the population. Their religion and languages became predominant. The Jutes, the Saxons and the Angles were much alike in speech and customs. When the Angles and the Saxons migrated to the British Isles, their language was torn away from the continental Germanic dialects and started its own way of development. At first, the Germanic invaders spoke various dialects but gradually the dialect of the Angles of Mercia prevailed. They also intermixed with the surviving Celts and gradually merged into one people – the Anglo-Saxons as they were called by the Romans and the Celts. Already in the 8th century they preferred to call themselves Angelcyn – Anglish/English people, and called the occupied territories Angelcynnes land – land of the Anglish/English people, which later transformed into England. The language they now spoke was called Anglish/English.

The 5th century marks the beginning of the history of the English language. The history of the English language can be divided into four periods:

- Old English period (OE) – from the mid-5th to the late 11th century

- Middle English period (ME) – from the late 11th to the late-15th century

- New English period (NE) – from the late 15th century up to the 21st century, including Modern English period – from the 19th century and up to now.

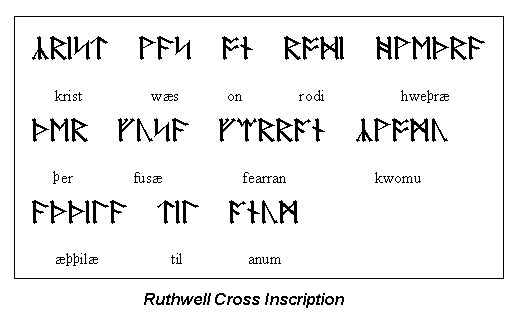

Germanic tribes used runic writing – a specifically Germanic alphabet with runes carved in stone, bone or wood with vertical or slanted lines. The number of runes in different Old Germanic languages varied: from 16 or 24 runes on the Continent to 28 or 33 runes in Britain. Runes were never used in everyday writing. The word ‘rune’ itself originally meant ‘secret, mystery’ that is why the main function of runes was to make short inscriptions on objects, which was thought to give them some magic power. The number of objects with runic inscriptions in Old English is about forty: amulets, coins, weapons, rings, tombstones, fragments of crosses. The two best preserved records of Old English runic writing are the text on the Ruthwell Cross in the village of Ruthwell in Scotland, and Franks Casket – a whalebone box found in France, which was given as a gift to the British Museum by a British archeologist A.W. Franks.

Later, Christian missionaries introduced the Latin alphabet to which several runic letters were added to mark the sounds [Y] and [T]. These were the letters Þ and T as well as the letter G which in certain positions was pronounced as [g] or [j]: GeonG [jeong] – young, Grene [grene] – green. The OE verbs sittan, beran, teran, findan, sinGan are quite recognisable. The first English words written down with Latin letters were personal names and place names which were inserted into Latin texts.

The Germanic tribes were pagans who worshipped the Sun, the Moon and a whole number of gods. Their principal gods were those of later Norse mythology – Tiw, Woden, and Thor. They are remembered in the day-names Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday as well as a number of place-names (Tuesley, Wednesbury, Thursley) which were presumably cult centres. Even when converted to Christianity, the Saxons named one of the main church festivals, Easter, after their old dawn-goddess Eostre.

The origin of day names

| Day names | Germanic god(dess) | His / her status | Roman / Greek gods | Planets and stars |

| Monday | – | – | – | the Moon |

| Tuesday | Tiw | The god of war | Mars / Ares | – |

| Wednesday | Woden | The god of commerce | Mercury / Hermes | – |

| Thursday | Thor / Thur | The God of thunder | Jupiter / Zeus | – |

| Friday | Frigg / Freya | Woden’s wife / the goddess of prosperity | – | – |

| Saturday | – | – | – | the Saturn |

| Sunday | – | – | – | the Sun |

The Anglo-Saxon word-stock consisted mainly of words of the Germanic origin. Most of them have correlations in the Indo-European languages:

Words belonging to the Indo-European Family of languages

| Latin | Modern German | Old English | Modern English | Russain |

| pater | Vater | fWder | father | (патриарх) |

| mater | Mutter | modor | mother | мать |

| frater | Bruder | broTor | brother | брат |

| unus | ein | an | one | один |

| duo | zwei | tu, twa | two | два |

| tres, tria | drei | Þri, Þrie | three | три |

| junior | jung | GeonG | young | юный |

| novus | neu | neowe | new | новый |

| dies | Tag | dWG | day | день |

The invaders were engaged in farming and cattle-breeding. The names of Anglo-Saxon villages usually had the root ham meaning ‘home, house’ or ‘protected place’: Nottingham, Birmingham. The Saxon ton stood for ‘hedge’ or ‘a place surrounded with a hedge’, as in Brighton, Preston, Southampton. The Saxon for ‘fortress, town’ was burG or burh which we now see in Canterbury, Salisbury, Edinburgh; feld meant ‘open country, field’ and it is seen in the names of Sheffield, Chesterfield, Mansfield.