Ноземна філологія inozemna philologia 2007. Вип. 119. С. 3-6 2007. Issue 119. Р. 3-6

| Вид материала | Документы |

- Ноземна філологія inozemna philologia 2007. Вип. 119(2). С. 3-9 2007. Issue 119(2)., 4217.57kb.

- Проблеми слов’янознавства problemy slov´ianoznavstva 2007. Вип. 56. С. 112-119 2007., 188.23kb.

- Камчатский государственный технический университет, 33.59kb.

- Публичный доклад муниципального дошкольного образовательного учреждения детского сада, 71.26kb.

- Лещинская, В. В. Альпинарии и камни в саду / Лещинская В. В.; [ ред. Рубайло, 14.35kb.

- Інформаційний вісник, 993.03kb.

- 04. 2003 №119, зареєстрованим у Міністерстві юстиції України 29., 120.44kb.

- Доклад моу «сош №119» г. Перми за 2008-2009 учебный год Общая характеристика моу "Средняя, 974.94kb.

- 04. 2003 №119, зареєстрованим у Міністерстві юстиції України 29., 265.54kb.

- 04. 2003 №119, зареєстрованим у Міністерстві юстиції України 29., 274.81kb.

4. 2 Visualization of Architectural Motifs

As far as the narration and content is concerned, one can encounter also interesting cases of architectural motifs. Columns, pyramids or towers are among popular architectural motifs in visual poetry of former eras. They carry with them certain connotations, most frequently panegyric or funeral ones [10]. First of all, it is possible to identify static and dynamic architectural motifs.

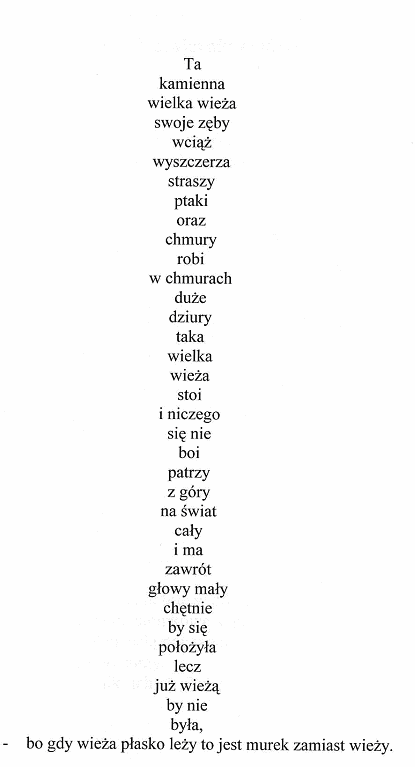

A dynamic example is well demonstrated in the ideographic text by Marcin Przewoźniak ^ Wieża [The Tower].

| [This tall tower, made of stone, its teeth still shows and scares away the birds and clouds makes holes in those clouds very large such tall tower stands and of nothing is afraid it looks down where the world slightly dizzy feels it would welcome laying down but it would no longer be called tower, – because when the tower lies flat it is a wall instead] |

In this poem two architectural forms are juxtaposed: monumental, tall vertical structure is contrasted with horizontal wall. The contrast is additionally emphasized by the length of the lines. There are 35 verses imitating the shape of the tower, each one to four-syllable long. Only the final verse, which consists of six syllables, can be associated with a long and low wall. Each word is arranged in separate line in, at most couples the are two words per line, and are centrally aligned so as to constitute the axis of the tower – the most important element of its structure. In this way the author illustrated the geometry of the tower so important for its stability. The message of this poem, then, has features characteristic of visual poetry because the words are arranged in a figure which in relation to its verbal message assumes mimetic and symbolic functions [10].

Przewoźniak employed a visual form of the poem here in order to illustrate the issues of spatial symbolism and the definition of an object in a form of a childlike “verbal diarrhoea.” The little reader receives here also an important ethical message: it is worth being outstanding and great like a tower, but to be oneself and to retain one’s greatness, it is necessary to be consistent and with effort maintain one’s conduct.

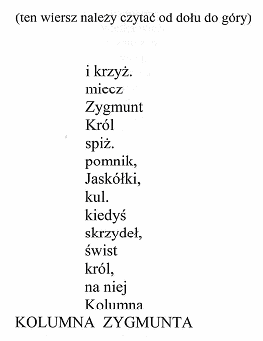

An example of a static architectural motif one can find in the poem ^ Kolumna Zygmunta [King Sigismund’s Column] by Kierst. The author begins it with the instruction that the poem ought to be read from the bottom. The technique of visualization that is present here also consists in transforming the symbolic sign into a motivated sign i.e. in transforming a group of words into an iconic sign which becomes the “picture” of the designatum [12].

| (this poem should be read from the bottom) and the Cross. sword King Sigismund, bronze. the monument, Swallows, of bullets. once the sound wings flutter, the king, there is on which The column ^ KING SIGISMUNT’S COLUMN |

At the very bottom of the text, spelled with capital letters, there is the title of the poem which in its graphic form constitutes the wide, horizontal base of the poem-monument. In the middle of this base, shorter lines (14) go up vertically and create the representation of the described object. The reader, who with accordance to the instruction reads the poem from the bottom, stands at the foot of the column, the one built by text and the one materialized in its description. The perspective of the observer who is standing at the bottom of the column is the same as the perspective of the reader beginning to read the poem from the line situated at the bottom. Subsequent elements of the column are presented in the enumeration-repetition mode of the poem [9]: the column, the swallows, the monument, the bronze, the king, the sword and the Cross.

The vertical arrangement of the subsequent elements of the poem-picture possesses also evaluative content. For in this way a kind of axiological ladder is created. On the top levels of this ladder, even above the king, there are the sword and the Cross – the symbols of God (faith) and Motherland (or rather heroic fight to defend it). King Sigismund’s Column constitutes the apotheosis of these values and the poem by Kiers is devoted to their glorification [4].

^ 4. 3. Visualization of Spatial Arrangements

Spatial motifs are also quite common in the poetry for children. They are especially rewarding area of visualization processes. It is possible to observe the visualization of a spatial arrangement, the visualization of the space structure and the visualization of a shape.

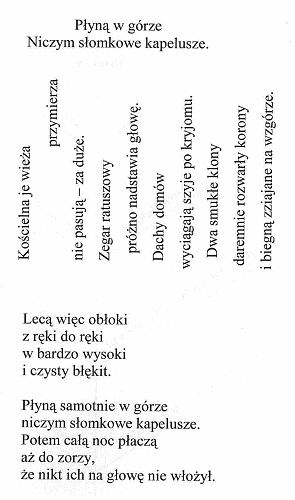

Visualization of a spatial arrangement is the subject matter of the poem ^ Obłoki [The Clouds] by Józef Ratajczak.

| T  hey float above hey float aboveAs if they were the straw hats. The clouds, then, run From left-hand-side to the right up the very high And clear blue sky. They float lonely above As if they were the straw hats. All night long They cry till dawn That no one will put them on. |

While two first stanzas are arranged in horizontal-vertical relation to each other and their shape creates two ideograms, stanza three and four are written in a traditional way However, in different reprints of the poem it is possible to find them arranged either one on top of the other or one next to the other. The first stanza of the two ideographic ones, arranged horizontally, consists of two lines: a shorter one and the longer one symmetrically oriented underneath the first one. Their shape reflects comparison to the clouds, which according to the content of the text float across the sky as if straw hats – topography of a hat. The form of a hat implies the graphic shape of the text arrangement representing a hat, through anthropomorphic presentation of the world described in the next stanza. These verses, this time arranged in an irregular vertical pattern, describe various tall objects on the surface of the earth: the church tower and the City Hall, high houses and maple trees. The beginning of the fourth stanza is the repetition of the first one, but this time it does not form a shape of a hat, because the shape is deformed by the added word “lonely.” Lonely and disappointed clouds assume anthropomorphic features: “All night long/They cry till dawn/That no one will put them on.”

In this context the vertical arrangement of the second stanza assumes a new meaning, namely it represents the streams of rain falling down from the clouds. The same graphic object enables child’s and poet’s imagination to see different meanings. Vertical lines going vigorously up in the sky towards beautiful clouds which are as if straw hats associated with warm and sunny weather. The movement down symbolizes sadness and hopelessness [4]. In this poem Ratajczak evokes both emotional experience and aesthetic sensitivity in the young recipients.

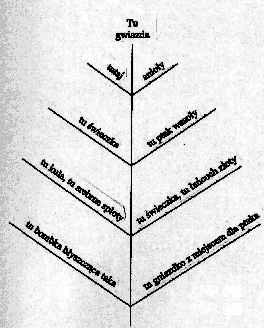

Moreover, the visualization of the space structure that is connected with building up the tension through the top-bottom arrangement of the content is present in Kern’s poem Choinka [The Christmas Tree]. Antologia by Waksmund [11] in both its editions contains the poem’s shortened version, which is reduced to star and the initial four verses-banches arranged in a simple drawing. The identical iconographic shape appears in Wielkiej zabawie [The Great Fun] by Jerzy Cieślikowski [3] who borrowed the version from Przekrój, No. 714–716, 1958, but he added: “and so on till the last branch where the children their presents find.” The analyzed version of the poem comes from L. J. Kern’s collection of poems [7].

In this example, the shape of a Christmas tree is constructed through a specific arrangement of lines. The text implies a variety of potential activities that a child and an adult may do at the time of Christmas celebration. A child might enumerate the names of various Christmas tree decorations. An adult may play with the child in a guessing game about different talents of children (e.g. why has Ann got crayons); then child’s interests may be the subject of a game – a present that would be most desired by him/her but also most appropriate.

It is worth pointing out that the arrangement of the objects in the structure of the poem represents The Christmas Eve’s ritual in its hierarchy of values: first the spiritual ones, the religious aspect of the celebration, i.e. the prayer, reading of the Bible, breaking the wafer (Polish traditional at Christmas Eve) at the top, next the Christmas Eve dinner in the middle, and finally exchanging the gifts at the bottom. The Christmas tree-poem becomes an iconic symbol of the Christmas Eve indicating the proper way of celebrating it.

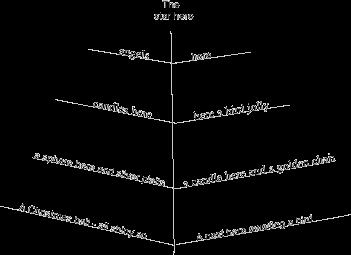

The visualization of a shape is also well demonstrated by Julian Kornhauser’s poem Gwiazdka [The Star]. This poem is a calligram which also assumes the shape of a Christmas tree.

[When the Christmas tree

Will play the needles that it has,

And the starlet will its beams stick out,

Leave the table seat and to the window come:

There Father Frost various presents is spreading round!

The cream-colour pajamas with patterns is waiting for you,

tiny thick cactus, and little chocolate as sweet as honey are waiting too.

If you try hard enough, you will hear how tired snow is snoring soundly.]

Out of the many types of iconic motivation that exist between the signifier and signified in concretist visual poetry, the allusion to Apollinaire’s calligrams is most apparent in the above-analyzed cases [4].

If compared with Kern’s poem, the graphic side of Kornhauser’s poem is characterized by simplicity as far as the visualization process is concerned. The figure is built of subsequent lines which become longer and longer and are symmetrically organized around the vertical axis. Due to the lack of any additional decorative elements, unless one is familiar with the content of the poem, the figure might be mistaken for a pyramid. For the structure is solid and stable, emphasized by appropriate syntactic and metrical arrangement (each verse, except for the first one, ends with a punctuation mark). The visual form of this poem, however, does not play as important role as in the case of the previously analyzed poems. It is just an addition, a graphic allusion to its topic. The essence of this poem’s phenomenon consists in its content and stylistics. Similarly as in Kern’s poem, the lyrical subject, an adult person, addresses a child. He understands child’s imagination and emotional states. He can enter child’s personal world and spend together with him Christmas time. It is expressed not only by the diminutives used in the text: “a starlet, tiny cactus, little chocolates,” but also by personification and animation of the surrounding world: “the Christmas tree will play the needles, the starlet will stick out little beams.” These expressions allude to children’s games – playing the needle that is stuck into a table and a popular conversation with a snail: “snail, oh snail, stick your little horns out.” The child is inspired to “play” the branches of the Christmas tree (which should emit a rustling sound), to invite the invisible still starlet to “stick out its beams.” In the following part of the poem, the invitation to join in takes form of an explicit encouragement to act because of the imperative forms used there: “Come, look.” The child is, then, both an addressee and the protagonist of the poem.

^ 4. 4. Visualization of the Veristic Description of Objects and Phenomena

Veristic technique of visualization is very close to child’s examination of the world. In the poetry for children, however, it exists less frequently than the cases of visualization mentioned above. Within veristic description it is possible to differentiate between visualization of objects alone and the letter-sign technique of visualization which creates certain phenomena in a given poem.

Veristic visualization of the objects has a pride of place in children literature. Kern’s poem entitled ^ Na kanapie [On the Sofa] can serve as an example. It is a poem-sofa in which the graphic arrangement of stanzas, varied length of lines and the presence of exclamatory sentences with the onomatopoeic character due to the poem’s trochaic meter – they all play the key role for the realistic representation of the animal subject matter.

[On the Sofa

Who is snoring

On the sofa?

Who is scratching

Its long ears?

Who when angry

Bares its teeth?

Who sometimes

Feeds the fleas?

Who thinks often

Of games?

Of tricks naughty?

Who likes chasing

Cats or pigeons?

Who bites at

His master’s sleepers?

Barks at milkman

In the morning?

Who with children

Plays joyfully

But by whom thief’s trousers

Will be caught painfully?

So you know now?

Then all hush!

Why should you want

To wake the dog up…

The author achieved the veristic representation of the shape of a popular piece of furniture by means of characteristic arrangement of the stanzas organized horizontally (cf. with similar case in the poem ^ Dwa rękawy [Two Sleeves]). They are so organized in relation to each other as to create the allusion to a soft, three-arched back of a sofa. The title also imitates an arched line and is placed over the central part of the furniture’s back, which imitates the visual description of the sofa constructed so as to sit down or lay down on it with pleasure. The bolder font and larger size of letters bring to one’s mind an allusion to a wooden decoration of the upholstery.

Each part of the sofa retains the poetics of children riddle, i.e. a nursery rhyme based on a structure of a folk riddle. The text creates a funny illusion of difficulty in guessing the simple meaning. It does not require a huge effort from imagination and provides the little reader with entertainment. The first stanza consists of four distich questions and the fifth question in a form of enjambment which ends in the second stanza. In this part of the poem, the punctuation, question marks and simple rhyme-clues (such as: “chrapie – kanapie”, ‘kanapie – drapie”, “zły – kły”, ‘kły – pchły”) play an important role.

The question mark, which is used here multiple times, belongs to the punctuation of emotion – its basic function is to demonstrate the emotional states of the speaker. The speaking subject, hidden behind the real world which is represented in the poem, expresses his warm feelings towards the amiable, resting creature. Similar attitude towards the sleeping character in the poem is assumed by the little readers, who enjoy playing with dogs and can easily imagine the body that slides down, because the entire situation is designed by the author to veristicly reflect the reality which is well known to all owners of dogs.

Visualization is, then, a characteristic feature of the poetry for children and the one which remains in agreement with psychophysical construction of the young recipient. It is possible to differentiate between several kinds of visualization creation that represent narrative structures, content and sound layers in the graphic form of the poem and constitute its picture and they were the basis for creating the above taxonomy. Simultaneously, each of the analyzed poems is a masterpiece with their unique narrative, content and sound structure. Some of these poems are closer to concrete poetry, but majority of them build connotative potential of an open structure and this potential is to be realized by the child-recipient. For the visualization of these poems is not merely about finding an iconic sign for them, as it was the case with concrete poetry.

1. Białek, J. Z. Ed. J Pisma wybrane, Maria Konopnicka. Utwory dla dzieci, Jan Nowakowski (Ed. of the series) Warszawa 1988. 2. Carroll, L. Przygody Alicji w krainie Czarów, Trans. M. Słomczyński, Warszawa 1972. 3 Cieślikowski, Sposoby istnienia bajki dziecięcej, [in:] Literatura i podkultura dziecięca, Wrocław; Warszawa; Kraków 1974. 4. Falicki, J. Kod słowny a kod rysunkowy. Próba typologii utworów piktograficznych na przykładzie “Kaligrafów” Apollinaire`a. Lublin 1988. 5.Gomringer, E. (1996) Visuelle Poesie. Antologie. Stuttgart. 6. Grochowski, G. “Na styku kodów. O literackich użyciach znaków ikonicznych”. Teksty Drugie. 2006, No. 4. 7. Kern, L. J. Wiersze pod choinkę, Warszawa 1983. 8. Milne, A. A. Kubuś Puchatek, Trans. I. Tuwim, Warszawa 1984. 9. Ostasz, M. “O wyliczeniowo-repetycyjnym modelu wiersza Marii Konopnickiej.” Guliwer. 2003, No. 3. 10. Rypson, P. Piramidy – słońca – labirynty. Poezje wizualne w Polsce od XVI do XVIII wieku. Warszawa 2002. [11] Waksmund R. (Ed.) Poezja dla dzieci. Antologia form i tematów, 2nd edition 1999. 12. Wysołuch, S. “Od poezji konkretnej do poezji (?) wizualnej,” [in] Literatura i semiotyka. Warszawa 2001.

^ ПРО ДЕЯКІ МЕТОДИ ВІЗУАЛІЗАЦІЇ В ДИТЯЧІЙ ПОЕЗІЇ

Марія Осташ

Аналіз ідеографічної поезії iз застосуванням низки методів візуалізації та адресованістю юному читачеві, – предмет цього дослідження. Цей спосіб унаочнення віддзеркалює наративну структуру, смисловий та звуковий пласти поеми в її графічній репрезентації. Варто наголосити, що візуальна поезія дуже важлива для молодого сприймача, для якого картина – важливий елемент механізму сприйняття і властивий компонент вербального тексту. Мислення дитини насамперед наочне. Варто розглянути тексти багатьох авторів. Наочність – характерна риса дитячої поезії і така, що гармонує з психофізичною структурою молодого сприймача. Можна розрізняти процес творення наочності, поданий наративними структурами, смисловим і звуковим пластами, та графічною формою вірша. Можна зауважити, що кожен з аналізованих віршів – це шедевр з властивою лише йому наративною, смисловою та звуковою структурами. Деякі з цих віршів ближчі до реальної поезії, проте більшість з них творять конотативний потенціал відкритої структури і цей потенціал належить реалізувати дитині-реципієнтові. Подібні ідеографічні методи застосовували Алан Александер Мілн та Льюїс Керрол. Є й неповторні візуальні вірші, написані польськими авторами, як-от: Марія Конопніцька, Марцін Пшевозьняк, Людвік Єжи Керн, Єжи Кєрст, Юліан Корнгаузер, Єжи Гарасимович та Юзеф Ратайчак. Їхня поезія творить собою цікаві форми з погляду графіки. Вірші, вибрані для доповіді, представляють процес унаочнення. Їхнє призначення – предмети, тварини, рослини і явища. Терміни “visual poetry, graphic rhyme, caligram, carmen figuratum” вживаються стосовно літературного явища, оскільки, на думку автора, належать до змісту тексту, надаючи йому й додаткових значень. Термін visual poetry – найзагальніший,він включає значення всіх інших. Його вживає польський дослідник Пьотр Рипсон. Серед видів уяви, вживаних у дитячій поезії, можна розрізняти: уяву світу природи, архітектурних компонентів, просторових структур та істинного (veristic) опису речей і явищ. Приклади згаданих видів уяви подано в доповіді в рамках формального аналізу, виконаного на основі вибраних рим.

Ключові слова: наочна поезія; графічна рима; каліграма; carmen figuratum.

УДК 821.111(73)’06-312.1.09 Д.Джорж

^ DOUBLE IDENTITY AND INTERCULTURAL COMMUNICATION

IN LITERATURE

Darja Mazi-Leskovar

University of Maribor, Slovenia

The paper “Double Identity And Intercultural Communication In Literature” explores the cross-cultural communication presented in the award-winning young adult novel ^ Julie of the Wolves (1972) written by the American writer and researcher Jean Craighead George. The aim of the paper is to analyse the specificity of intercultural encounters taking place on the inter- and intrapersonal levels.

Key words: double cultural identity; monocultural; bicultural; tradition; intercultural communication; cross-cultural encounters; Eskimo; Anglo-American; novel.

Multicultural literary texts in which characters belong to two different cultures have cross-cultural appeal. By targeting readers of several cultural traditions, they have a privileged position among texts addressing multicultural issues. The specificity of multicultural literature that presents characters with double cultural identity is that cross-cultural encounters take place not only on the interpersonal but also on the intrapersonal levels. Such literature, therefore, doubly highlights the issues related to the multicultural awareness, which is considered to be a prerequisite for successful intercultural communication.

Multicultural awareness in the literary characters who belong to two different cultural backgrounds is invaluable. Firstly it is because quality multicultural literary texts are considered to be endowed with the power to help readers see the world through the eyes of literary characters. Secondly, because it is anticipated that the mere fact of viewing two cultures as one’s own requires, on the one hand, constant communication at the intrapersonal level, and, on the other hand, demands some degree of critical distance between opposing cultural principles determining the two cultures. Special credit for the fact that literature is still regarded as one of the most promising assets humanity has at its disposal to raise the awareness of the importance of intercultural communication can be, therefore, attributed to books presenting double cultural identity.

Among books that feature main characters who belong to two cultures, the American prize-winning novel Julie of the Wolves (1972) by Jean Craighead George, an acclaimed writer and researcher of the Arctic habitat ranks high. By presenting a specific mode of intercultural encounters, the book encourages readers to reflect on the issues related to contemporary life and global society. This paper will, therefore, explore how the protagonist’s awareness of two different cultures develops and how her views about the two cultures undergo alterations. Additionally, this paper will put special stress on the struggle of the heroine to determine her personal identity, which leads to her maturation and acknowledgement of her own responsibility for her own personal happiness.

The key concept of this paper, intercultural communication, is used in this context in accordance with the adopted meaning recognized by communication theory and practice. Thus the term ‘communication’ is seen as the process which “requires interaction within oneself and between people”, [5, p. 261]. The meanings of the terms ‘intercultural’ and ‘cross-cultural’, which are used interchangeably, are, consequently, to be understood within the context of identifications of word culture in terms of nation, area, race or religion [5].

The quests of the protagonist to find her own way in the complicated intersections of cultures and her struggle to articulate her own changing attitudes will be thus viewed within the larger meaning of the concept ‘culture’, which embraces both traditions and practices of varied groups of individuals. Since the heroine progressively discovers that culture is not rigid and unchanging, Stuart Hall’s notion of fluidity of culture will be applied. Hall developed his theory on the basis of diasporic situations and explained it in his Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies (1996). According to his research, characters who are supposed to belong to two ethnic entities tend to develop a distinctive type of personal culture which is based on a critical distance developed towards each of the two traditions. Hall claims that this is the principal reason why most of those individuals cannot completely fit in either of the two cultures they have grown into. Such a situation, however, is not limited to diasporic individuals since it also arises when characters who by origin belong to one culture live in an environment that fosters another culture. Consequently, Hall’s theory is also applicable to Inuit culture, which can be encountered in various states, in different political frameworks, where the Inuit tradition is confronted with other cultural backgrounds.

Inuit culture is referred to in Craighead George’s novel also as Eskimo culture. In compliance with the author’s usage, the two terms will also be used indiscriminately in this text. The setting, the territory of the USA, underpins the justification of the appellation ‘Eskimo,’ as it is still in general usage outside of Canada to refer to all Inuit peoples [6].

The paper will, furthermore, examine the intercultural encounters in the light of Werner Sollors’ theory on various types of links which determine an individual’s relationship to a particular culture. Sollors’ interpretation of consent and descent appears to be most suitable for the analysis of intercultural encounters. Sollors uses the term ‘descent’ in compliance with the general usage defined in The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary as “the fact of descending or being descended from an ancestor or predecessor” [2, p. 643]. Descent relations, thus, reveal a person’s origin. Sollors’ term ‘consent relations,’ on the other hand, expresses the relations that are not determined by nature or birth but by environment and individual choices. These encompass both the ones based on voluntary agreement and those based on acquiescence. Within the context of this paper, consent relations appear to be of particular importance since they are a testimony to the fact that we, humans, are capable of acting “as mature free agents and ‘architects of our fate’” [12, p. 6].

^ THE INTERPLAY BETWEEN INTRA– AND INTERPERSONAL CROSS-CULTURAL COMMUNICATION

Julie of the wolves, the 1973 winner of the Newbery Medal, is a young adult novel with a multi-layered story which, viewed from various perspectives, allows for various classifications. The basic outline of the action allows the book to be defined as a tale of maturity and a wilderness survival quest story [8, p. 120]. However, the story is also a tale of intercultural encounters. These are of double nature: the usual ones, occurring among individuals belonging to different nations and traditions, and the ones taking place on the level of intrapersonal communication. The complexity of the latter increases drastically during the evolution of the story, since the survival of the eponymous heroine depends on the success of her quest for personal identity, split as she is between American and Inuit cultures.

The book is divided into three sections, each of which sheds specific light on the issue of intercultural encounters experienced by the heroine, who has been confronted with both Inuit and American cultures from an early age. However, as far as her descent is concerned, it is clearly put in the opening section that she is purely Inuit.

Miyax was a classical Eskimo beauty, small-boned and delicately-built with strong muscles. Her face was pearl-round and her nose was flat. Her black eyes, which slanted gracefully, were moist and sparkling. Like beautifully-formed polar bears and foxes of the north, she was slightly short-limbed [3, p. 8].

Even though descending from Eskimo parents, the girl has inherited not only the diachronic link with Eskimo culture but also its consent relations with Anglophone culture. In accordance with Sollors’ framework, this may be regarded as a contradiction in itself, even though it may well reflect a contemporary lifelike situation, particularly for the members of minorities in multi-ethnic states. Thus main character’s connection with the English-speaking culture has originated from her cradle. Her relation with the culture of white Anglophones, therefore, shares the decisive aspect of involuntary exposure, which is one of the basic features of descent relations. The bicultural relation is also symbolically indicated with her two names: Julie and Miyax. However, even though the cultural climate she grows into as a small girl is bilingual, she considers herself to be an Eskimo, which is also the obvious consent relation of her father Kapugen.

Eskimos from Mekoryuk spoke English almost all the time. They called her father Charlie Edwards and Miyax was Julie, for they all had two names, Eskimo and English. Her mother had also called her Julie, so she did not mind her summer name until one day Kapugen called her by it. She stamped her foot and told him her name was Miyax. “I am Eskimo, not a gussak”, she said and he tossed her into the air and hugged her to him [3, p. 80–81].

This sense of belonging to Eskimo culture grows during the years after her mother’s death, when she lives alone with her father in the settlement where Eskimo ways and traditions have remained an integral part of life. Not only festivities where life and death, present, past and future are interconnected but also regular storytelling about man’s struggle for survival have gradually introduced her in the secrets of her people’s existence.

The celebration of the Bladder Feast was multicolored – black, blue, purple, fire-red. The shaman, an old priestess whom everyone called “the bent woman,” danced. Her face was streaked with black soot. When she finally bowed, a fiery spirit came out of the dark wearing a huge mask… Later that day Kapugen blew up seal bladders and he and the old man carried them out on the ice. There they dropped them into the sea while Miyax watched and listened to their songs. When she came back to camp, the bent woman told her that the men had returned bladders to seals.

“Bladders hold the spirits of the animals,” she said. “Now the spirits can enter the bodies of the newborn seals and keep them safe until we harvest them again” [3, p. 77].

Later, when Miyax had to leave her father in order to go to school in Mekoryuk, she re-entered the environment where Inuit culture intermingled with Anglophone culture. She was called Juliet again and she started to discover gaps between the two ways of life. For instance, when visiting a school friend, she saw for the first time a gas cooking stove, a couch, framed pictures on the wall, and curtains of cotton print. Then Judith took her into her own room. On the table lay a little chain on which hung a dog, a hat, and a boat. This she was glad to see – it was something familiar.

“What a lovely I’noGo tied!” Julie said politely.

“A what?” asked Judith. Julie repeated the Eskimo word for the house of the spirits.

Judith snickered. “That’s a charm bracelet,” she said. Rose giggled and both laughed derisively. Julie felt the blood rush to her face as she met, for the first but not last time, the new attitudes of the Americanized Eskimos. She had much to learn besides reading. That night she threw her i’noGo tied away [3, p. 85–86].

The materialistic culture and the spiritual culture of Eskimos have given way to White American gadgets and to the Western perception of the world. The heroine desires not to be laughed at and in her wish to be like others, accepts the changes as something she should get accustomed to. Such a standpoint enables her to make an important step towards building her consent relations with Anglophone culture. Her positive attitude towards Americanized ways is strengthened when she gets a pen pal. Amy’s letters from San Francisco become such an important part of Julie’s life that, being in serious trouble, she decides to accept Amy’s invitation to come to her. She escapes, planning to leave the Arctic by finding the way southwards to California. She believes she knows where she is heading because “she could imagine the arched doorway, the Persian rug on the living-room floor, the yellow chairs and the huge window that looked over the bay” [3, p. 98].

However, when she gets lost in the snow, she has to admit that she is no more in a position to find the shortest way possible to reach her destination. For some time she continues to dream about the life awaiting for her in the south, seeing herself as “Miyax, daughter of Kapugen, adopted child of Martha, citizen of the United States, pupil at the Bureau of Indian Affairs School in Barrow, Alaska” [10]. Her vision of her life with Amy’s family is in striking contrast to the austere reality of her Alaskan existence, so it becomes one of the sources that give her the power to survive. She has refused her Eskimo part, her name Miyax which “stands for whatever is related to the Inuit lore” [10, p. 50]. As Julie, she can see herself continuing her schooling and enjoying the same luxuries as her friend living in a prosperous part of America. However, when she is in such trouble in the Arctic that her very existence is endangered, she discovers that simple objects she need to survive, for example, tiny needles, are more precious than the huge symbols of American prosperity like airplanes and bridges. Thus her dream starts losing some of its enchantment. Moreover, when she reflects about the qualities that Eskimos traditionally identify as signs of wealth, fearlessness, intelligence, and love, she becomes increasingly convinced that it is the Eskimo richness that makes a person happy. The attraction of the faraway society further diminishes when her eyes open to the importance of the ability to communicate with animals, especially with wolves, and to the beauties of the environment that her journey leads her through. Nature with its beauty, associated with the world of Eskimos, finally pushes the American civilization from the pedestal. Julie consents to admit that Eskimo culture is worth admiring.

“The old Eskimos had changed the harsh Arctic into a home, a fact as incredible as sending rockets to the moon. The people at seal camp had not been as outdated and old-fashioned as she had been led to believe. No, on the contrary, they had been wise. They had adjusted to nature instead of to man-made gadgets” [3, p. 121].

The final blow to Julie’s vision of life in the non-Eskimo world comes from her witnessing the slaughter of the wolf that has saved her life. Understanding that they killed him for the pure pleasure of hunting, she knows that she cannot accept the culture that has created this sort of sport. She would like to live like an Eskimo. She starts cherishing a new dream. However, she does not sever herself completely from her western heritage. From time to time she tries “to spell Eskimo words with the English alphabet (as) such beautiful words must be preserved forever” [3, p. 153].

This unconscious premonition that Inuit culture can survive only if related to the American expression or it announces another much more radical compromise Julie will have to make later in the story. Her great plans for an independent life according to the ancient traditions receive a serious blow when she realizes that even her father has changed his way of life. He has married a white woman, speaks English, has his house equipped with modern household equipment and even uses a plane to help white hunters on their pursuit of large animals. Miyax understands that he has turned his back on several of the ways determining Eskimo traditions. Despite her deep need to live in the community and particularly near her father, her first reaction is to renounce her father whom she used to regard as a living example of fidelity to Eskimo culture. She cannot understand how he could have accepted a culture that does not respect what Eskimos have always cherished. However, after having realised that she cannot survive alone, she decides to join her father and to accept the new ways of life the Eskimo community has adopted.

CONCLUSIONS

The novel ^ Julie of the Wolves illustrates how the main character’s awareness of her double identity develops through the changing perception of the two traditions which represent the roots of her personal cultural identity. The book thus offers a story about the search for cultural identity of the main character who is a citizen of the country where the majority of the population belongs to another ethnicity, race and tradition. Her American citizenship is a component of her personal identity that is not questioned; the rest of her cultural identity, on the other hand, undergoes serious scrutiny, which results in changing consent relations. Before providing the summarized overview on the various stages that the protagonist’s personal identity goes through, it is necessary to underline that Miyax never questions her double identity, even though her descent is clearly monocultural. This will also be the main reason why the seeds of two traditions, sown due to the encounter between the indigenous and the Anglo-American cultures, seem to develop harmoniously until the point when the author positions one culture in the forefront: when Miyax’s mother dies, the first severance of ties with Anglo-American culture takes place. Her father enables her to nourish her Eskimo identity. Miyax’s early memories are thus impregnated with Eskimo culture only.

The first moment of tuning in to cultural history of which she is aware comes when she is separated from her father in order to enter school. Even though this separation brings the confirmation of her Eskimo consent, it leads to the severance of ties with the culture she has been growing into. The flashbacks of the story clearly position the start for her schooling as the trigger of the process of “de-Eskimozation” which will result in Julie’s rejection of Eskimo culture. When she is later confronted with the unconfirmed news of her father’s death, she finds herself in the position of an orphan. Even though legally her status is amended by an adoption, on a symbolic level the loss brings her independence with regard to the creation of her cultural identity. It is up to her not only to determine her consent relations but also cope with the culture shock. Her self-esteem drops drastically, and she strives to develop an image of herself as she would like to be and as she would like others to see her [5]. She shows her growing maturity and flexibility by deciding to integrate into the “Americanized” Eskimo environment, but on the other hand accepts the fact that culture is not static and its active components undergo changes. The second change in her attitude to her double identity brings also a critical response to whatever is Eskimo. A new consent relation to Americanized Eskimo culture, which fortifies above all the Anglo-American part of her identity, is also kept in another Eskimo cultural context that she moves out of her own free will. Her increasing maturity and critical distance enable her to take a radical decision and to decide in favour of Anglo-American culture where she expects to be given the respect and opportunities that she cannot experience in her native environment. Her consent to cultural affiliation has undergone the third change.

The fourth change occurs when the Anglo-American source of the protagonist’s double identity is scrutinized. When Julie is confronted with a few harsh aspects of Anglo-American culture, her quest for the life offered by the non-Eskimo civilization ironically pushes her toward the tradition of her ancestors. However, the image of life according to the old Eskimo ways reveals itself as another illusion that needs rectification. It is the fifth alteration in her consent relations that reveals her maturity through sacrifices of parts of both her identities in order to defend her right to live. She will be able to survive as an individual responsible for her own happiness and as a member of a larger community in Americanized Eskimo culture, which is a fluid and not self - enclosed entity.

The intermingling of changes observed on the protagonist’s personal level, which are the result of her efforts to determine her own cultural identity, is accompanied by the image of changes occurring in the Eskimo society. Consequently, readers can easily draw parallels between changes occurring in the life of the protagonist and transformations taking place on a larger scale in the community to which Miyax relates. Thus Julie of the Wolves encourages readers to think about the role of intercultural encounters in the process of identity formation and shaping of cultures.

Another quality of this novel is that by the end of the narrative it clearly shows that, despite her double cultural identity, the heroine’s personality is not split. By illustrating the maturation that results in the main character’s inner stability, the narrative seems to be persuading readers not to be afraid of facing multicultural issues of the contemporary world. Last but not least, a distinctive feature of the book is that it offers a reference point both for the increasing number of young readers with bicultural identity and for all those monocultural readers who are curious about challenges faced by people rooted in two cultures.

1. Bredella, Lothar. 2005. “Intercultural understanding with multicultural literary texts”, p .54-55 in Towards intercultural communicative competence in Europe and beyond. Koper: University of Primorska, Science and Research Centre of Koper. 2. Brown, Lesley. 1993. “The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. 3. Craighead George, Jean. 1972. Julie of the Wolves. New York: Harper. 4. Defonseca, Misha. 2006. Preživela z volkovi. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga. Translation of Survivre avec les loups. 2005. Paris: XO Editions. 5. Dimbleby, Richard and Graeme Burton. 1998. More Than Words. An Introduction to Communication. New York: Routledge. 6. Dorais, Louis and Jacques Quaqtag. 1997. Modernity and Identity in an Inuit Community. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. 7. Hall, Stuart. 1996. “The Formation of a Diasporic Intellectual: An Interview with Stuart Hall by Kuan-Hsing Chen.” In Stuart Hall: Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. Ed. David Morley and Kuan-Hsing Chen. London and New York: Routledge. 8. Hourihan, Margaret. 1997. Deconstructing a Hero. New York: Harper. 9. Mannur, Anita. 1999.“At Home in an Indian World. Construction of Ethnicity in the Works of Farrukh Dhondy and Malcolm Bosse.“ In Bookbird Vol. 37, No. 2, 1999/23, p. 18 – 23. 10. Mazi-Leskovar, Darja. 2004. “A Happy Blend of Universality and Novelty: Julie of the Wolves and A Ring of Endless Light as Stories Crossing the Animal-Human Boundary” in Van der Walt, Thomas, Fairer-Wessels, Felicite and Inggs, Judith (eds). Change and Renewal in Children’s Literature (Contributions to the Study of World Literature, 126). London, New York: Praeger, p. 47-57. 11. Morley David and Kuan-Hsing Chen (ed.).1996. Stuart Hall Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies. London: Routledge. 12. Sollors, Werner. 1986. Beyond Ethnicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 13. Sollors, Werner. 1989. The Invention of Ethnicity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.