Б. А. Ильиш строй современного английского языка Учебник

| Вид материала | Учебник |

- Advanced English Course: Лингафонный курс английского языка. Арс, 2001; Media World,, 641.95kb.

- Программа дисциплины опд. Ф. 02. 3 Лексикология английского языка, 112.16kb.

- Н. Н. Этимологические основы словарного состава современного английского языка. М.,, 8.77kb.

- Рабочая программа дисциплины лексикология современного английского языка наименование, 245.25kb.

- Программа дисциплины дпп. Ф. 08. 3 Грамматика Цели и задачи дисциплины, 108.5kb.

- Вопросы по курсу «Теоретическая лексикология современного английского языка» 2007, 39.13kb.

- С. Ф. Леонтьева Теоретическая фонетика английского языка издание второе, ■исправленное, 4003.28kb.

- Встатье рассматривается многокомпонентное словосочетание современного английского языка, 194.54kb.

- Межотраслевая полисемия в терминологической системе современного английского языка, 924.34kb.

- Библиотека филолога и. Р. Гальперин очерки по стилистике английского языка, 6420.74kb.

108 The Verb: Mood

W

e cannot give here a complete list of patterns. However, such a list is necessary if the conditions of a peculiar application of the lived or knew forms are to be" made clear.

e cannot give here a complete list of patterns. However, such a list is necessary if the conditions of a peculiar application of the lived or knew forms are to be" made clear.We might also take the view that wherever a difference in meaning is found we have to deal with homonyms. In that case we should say that there are two homonymous lived forms: lived1 is the past indicative of the verb live, and lived2 is its present subjunctive (or whatever we may call it). The same, of course, would apply to knew and to all other forms of this kind. However, this would not introduce any change into the patterns stated above. We should only have to change the heading, and to say that, for example, Pattern No. 1 shows the conditions under which lived or knew is the form of the present subjunctive. It becomes evident here that the difference between the two views affect the interpretation of grammatical phenomena, rather than the phenomena themselves.

A similar problem concerns the groups "should + infinitive" and "would + infinitive". Two views are possible here. If we have decided to avoid homonymy as far as possible, we will say that a group of this type is basically a tense (the future-in-the-past), which under certain specified conditions may express an unreal action — the consequence of an unfulfilled condition. 1

1 With these groups the problem is further complicated by the fact that both "should + infinitive" and "would + infinitive" have other meanings, besides the temporal and the modal ones, "Should + infinitive" can, as is well known, denote obligation and thus be synonymous with "ought + to-infinitive", whereas "would + infinitive" can also denote repetition of the action (as in the sentence He would come and sit with us for hours) and volition (as in the sentence Try as I might, he would not agree to my proposal). The exact delimitation of all these possibilities is a somewhat arduous task. A complete theory of the matter would require a complete list of patterns for every possible meaning of each group.

Here is an extract from a novel by Jane Austen which is interesting from this viewpoint: Thorpe defended himself very stoutly, declared he had never seen two men so much alike in his life, and would hardly give up the point of its having been Tilney himself. Since there is, in this sentence, a verb denoting speech in the past tense (declared) and an object clause attached to it, with its predicate verb in the past perfect tense (had never seen), it would be all but natural to suppose that would ... give up is a future-in-the-past and a second predicate in the object clause whose first predicate is had ... seen. It is only the lexical meanings of the words (hardly, give up) that show this interpretation to be a mistake: in reality the predicate would hardly give up is a third predicate in the main clause, whose first two predicates are defended and declared. From this it becomes evident that would hardly give up is a compound predicate, meaning, approximately, 'did not want to give up...' To illustrate further the importance of the lexical meanings, let us substitute other words for the ones in the text, leaving the pattern "would + infinitive" untouched; for instance, Thorpe defended himself very stoutly, declared he had never seen two men so much alike in his life, and would never believe it was another man. In that case the "would + infinitive" might quite well be the future-in-the-past.

The Other Moods 109

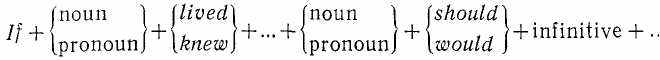

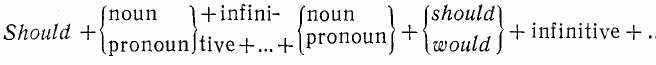

The patterns in which this is the case would seem to be the following (we will give only two of them) : Pattern No. 1:

Pattern No. 2:

As a third pattern, it would be necessary to give the sentence, in which there is no subordinate clause, e. g . I should be very glad to see him. Here, however, the distinction between the temporal and the modal meaning is a matter of extreme subtlety and no doubt many lexical peculiarities would have to be taken into account. Especially in the so-called represented speech (see p. 333) the conditions for the one and the other meaning to be realised are very intricate, as will be seen from the following extract: To the end of her life she would remember again the taste of the fried egg sandwich on her tongue, could bite again into the stored coolness of the apple she picked up from the red heap on a trestle table. ...She would never again see the country round Laurence Vernon's home as she saw it the first time with Roy. (R. WEST) A variety of factors, both grammatical and lexical, go to show that the meaning here is that of the future-in-the-past. Compare: But Isabelle could do nothing, she and Marc had been brought by the Bourges, who were now murmuring frenetically, that they would feel better at the Sporting Club (Idem), where it is hard to tell which meaning is preferable.

If we endorse the other view, that is, if we take the temporal and the modal groups "should (would) + infinitive" to be homonyms the patterns themselves will not change. The change will affect the headings. We shall have to say, in that case, that the patterns serve to distinguish between two basically different forms sounding alike. Again, just as in the case of lived and knew, this will be a matter of interpreting facts, rather than of the facts as such.

GROUPS WHICH OUGHT NOT TO BE CLASSED UNDER MODAL CATEGORIES

Among these we must mention first the groups let me go, let us go, and let him (them) go, i. e. the patterns "let + personal pronoun (in the objective case) or noun (in the common case) + infinitive' which may be used to denote (1) a decision of the 1st person sin-

110 The Verb: Mood

g

ular (i. e. of the speaker himself) to commit an action, or (2) an appeal to the 1st person plural, that is to one or more interlocutors to commit an action together with the speaker, or (3) an appeal to the 3rd person (singular or plural) to commit some action.

ular (i. e. of the speaker himself) to commit an action, or (2) an appeal to the 1st person plural, that is to one or more interlocutors to commit an action together with the speaker, or (3) an appeal to the 3rd person (singular or plural) to commit some action.There is the question whether groups of this structure can or cannot be recognised as analytical forms of the imperative. This question must be answered in the negative for the following reasons. The noun or pronoun following the verb let stands in an object relation to this verb. This is especially clear with personal pronouns, which are bound to appear in the objective case form: Let me go (not I), let him go (not he), etc. If we were to say that the formation "let + personal pronoun + infinitive" is a form of the imperative, we should have to accept the conclusion that the subject is expressed by a pronoun in the objective case (the nominative being impossible here), which is obviously unacceptable, as it would run counter to all the principles of English syntactic structure. This formation is therefore not an analytical form of the imperative mood, and the verb let not an auxiliary of that mood (or, indeed, of any other grammatical category). Expressions of the type let me go, let us go, let him go are therefore not in any way morphological phenomena. They belong to syntax. The imperative mood is represented by 2nd person forms only.

It might be argued that, since there are no other persons within the system of the imperative, the 2nd person is not opposed to any other person and does not therefore exist as a grammatical category. If we take this view we should have to say that there is no category of person at all in the imperative. This view is quite defensible, provided we take the system of the imperative as something existing in its own right and not within the wider framework of the verb system as a whole. If, on the other hand, we do place it in this wider framework we shall recognise that the form come (!) bears the same reference to person as the form (you) come (!) and we shall not deny it the right to be called a 2nd person form. Here, indeed, the decision arrived at will depend on the view we take of the problem on a wider scale.

MOOD AND TENSE

We have already discussed some relations between mood and tense in dealing with such forms as lived, knew, and such forms as should come, would come.

There are, however, some other problems in this field, which we have not so far touched upon.

First of all, there is the use of the future tense to denote an action referring to the present and considered as probable (not

Mood and Tense 111

c

ertain). We can illustrate this use by examples of the following kind: The House will know that... (used, for example, in parliament speeches).

ertain). We can illustrate this use by examples of the following kind: The House will know that... (used, for example, in parliament speeches).The sources of this use seem clear enough. The original meaning of such sentences seems to have been, approximately, this: 'It will appear (afterwards) that you know', etc.

In a similar way the future perfect can be used to denote an action which is thought of as finished by the time of speaking and represented as probable. This is seen in such sentences as the following: ...You'll not have spoken to her mother yet? (LINKLATER), which is equivalent to Probably you have not spoken to her mother yet? The origin of this use is analogous to that of the future as shown above. The sentence just quoted would have meant, 'It will appear (afterwards) that you have not spoken', etc. In the following example the future-in-the-past and the future-perfect-in-the-past are used in this way: I made for my lodgings where by now Melissa would be awake, and would have set out our evening meal on the newspaper-covered table. (DURRELL) It is the adverbial modifier by now which makes the meaning perfectly clear.

In this way both the future and the future perfect can acquire a peculiar modal colouring. As in some previous cases, we ought to look for certain patterns, including, probably, lexical as well as grammatical items, in which this modal colouring is found. 1

An interdependence between mood and tense which has a much wider meaning may be found if we analyse the system of tenses together with that of moods. When the question arises, how many tenses there are in the Modern English verb and what these tenses are, examples for that kind of analysis are always taken from the indicative mood. 2 Indeed, it is only in this mood that we find the system of tenses fully developed. In no other mood, however we may classify those other moods, shall we find the same system of tenses as in the indicative. The cause of this is evident enough: it is the indicative mood which is used to represent real actions, and it is such actions that are described by exact temporal characteristics. As to those actions which do not take place in reality but are thought of as possible, desirable, etc., they would not require a detailed time characteristic. Time is essentially objective, while all moods except the indicative are subjective.

1 A similar phenomenon is found in Russian, as when a verb in the future form (chiefly the verb быть) is used to denote something referring to the present, with a peculiar modal colouring, e.g. До меня верст пять будет (ТУРГЕНЕВ), А кто ж такая будете? (Idem) See В. В. Виноградов, Русский язык, стр. 575.

2 This is of course also true of Russian grammar: the analysis of the three tenses of the Russian verb is always based on material provided by the indicative mood.

112 The Verb: Mood

T

hings are quite clear in the sphere of the imperative. Since its basic meaning is an appeal to the listener to perform an action it is obviously incompatible with the past tense. A difference might exist between present and future, in the sense that the speaker might appeal to the listener to perform the action either immediately or at some future time. However, no such difference is found in the imperative forms either in English or in most other languages. 1

hings are quite clear in the sphere of the imperative. Since its basic meaning is an appeal to the listener to perform an action it is obviously incompatible with the past tense. A difference might exist between present and future, in the sense that the speaker might appeal to the listener to perform the action either immediately or at some future time. However, no such difference is found in the imperative forms either in English or in most other languages. 1As to the moods expressing condition, desire, and the like, the problem of tense is somewhat more complicated. If we compare the two well-known types of conditional clauses:

- If he knew this, he would come,

- If he had known this, he would have come,

we are faced with a complexity of interwoven problems. Evidently our interpretation of these phenomena will depend on our treatment of the forms knew, would come, had known, and would have come (see above).

If we take the view that knew is the past indicative which in this context is used to express an unreal action in the present, and would come the future-in-the-past, which in this context is used to express an unreal consequence in the present, there is nothing more to be said about the tense or any other category appearing in this type of sentence.

In a similar way, if we take the view that had known is the past perfect indicative which in this context is used to express an unreal condition in the past, and would have come the future-perfect-in-the-past which in this context is used to express an unreal consequence in the past, there is nothing more to be said about it.

If, on the other hand, we interpret the forms knew, had known, would come, and would have come as special mood forms, we shall have to characterise the difference between knew and had known and that between would come and would have come in another way. We shall have to find an answer to the question, what grammatical category underlies the oppositions:

knew — had known

would come — would have come.

Here we are faced with a peculiar difficulty. If we judge by the means of expression (the auxiliary have is used in the second

1 The Latin language does distinguish between a present imperative, e.g. dic 'say!' (now), and a future imperative, e.g. dicito! 'say!' (afterwards). But this distinction is rarely made use of.

Mood and Tense 113

c

olumn, but not in the first) we shall compare this opposition to

olumn, but not in the first) we shall compare this opposition tothat between

knows — has known

will know — will have known,

and reach the conclusion that the opposition is based on the category of correlation, as defined above. In that case there would not be any tense category at all in the system of these moods.

But it might also be argued that, according to meaning, the opposition is one of tense (present vs. past). In that case there would be the category of tense in these moods but no correlation.

The choice between these two views remains arbitrary. For the sake of the unity of the system it would seem preferable to stick to the view that wherever we find the pattern "have + second participle" it is the category of correlation that finds its expression in that way.

To sum up the whole discussion about the categories of the verb found in conditional sentences, the simplest view, and the one to be preferred is that we have here forms of the indicative mood in a special use. Another view is that we have here forms of special moods, and that they are distinguished from each other according to the category of correlation.

If we endorse the view that there are no homonymous forms in the English verb a sentence like if he knew this he would come will be interpreted as containing the past tense of the verb know and the future-in-the-past of the verb come, the very existence of mood as a special grammatical category in Modern English becomes doubtful, since it will appear lacking any specific means of expression. This might be the way to "cut the Gordian knot" of problems posed by the analysis of modal meanings in the verb.

This ends our discussion of aspect, tense, correlation, and mood.

Chapter XII

THE VERB: VOICE

The category of voice presents us with its own batch of difficulties. In their main character they have something in common with the difficulties of mood: there is no strict one-way correspondence between meaning and means of expression. Thus, for instance, in the sentence I opened the door and in the sentence the door opened the meaning is obviously different, whereas the form of the verb is the same in both cases. To give another example: in the sentence he shaved the customer and in the sentence he shaved and went out the meaning is different (the second sentence means that he shaved himself), but no difference is to be found in the form of the verb.

We are therefore bound to adopt a principle in distinguishing the voices of the English verb: what shall we take as a starting-point, meaning, or form, or both, and if both, in what proportion, or in what mutual relation? 1

As to the definition of the category of voice, there are two main views. According to one of them this category expresses the relation between the subject and the action. Only these two are mentioned in the definition. According to the other view, the category of voice expresses the relations between the subject and the object of the action. In this case the object is introduced into the definition of voice.2 We will not at present try to solve this question with reference to the English language. We will keep both variants of the definition in mind and we will come back to them afterwards.

Before we start on our investigation, however, we ought to define more precisely what is meant by the expression "relation between subject and action". Let us take two simple examples: He invited his friends and He was invited by his friends. The relations between the subject (he) and the action (invite) in the two sentences are different since in the sentence He invited his friends he performs the action, and may be said to be the doer, whereas in the sentence He was invited by his friends he does not act and is not the doer but the object of the action. There may also be other kinds of relations, which we shall mention in due course.

The obvious opposition within the category of voice is that between active and passive. This has not been disputed by any

1 Difficulties of a somewhat similar kind are also found in dealing with voices of the Russian verb. On the one hand, the same external sign (the, affix -ся) may express different meanings, viz. reflexive (бриться), reciprocal (ссориться), passive (строиться), etc., and on the other, the same meaning (passive) may be expressed both by the affix -ся and by the pattern "быть + participle in -н- or -м-", е. g. дом строился — дом был построен. See В. В. Виноградов, Русский язык, стр. 639 сл.

2 See Грамматика русского языка, т. 1, 1953, стр. 412. The problem is treated in Academician V. Vinogradov's book, p. 607 ff.

Active and Passive 115

s

cholar, however views may differ concerning other voices. This opposition may be illustrated by a number of parallel forms involving different categories of aspect, tense, correlation, and mood. We will mention only a few pairs of this kind, since the other possible pairs can be easily supplied:

cholar, however views may differ concerning other voices. This opposition may be illustrated by a number of parallel forms involving different categories of aspect, tense, correlation, and mood. We will mention only a few pairs of this kind, since the other possible pairs can be easily supplied:invites — is invited

is inviting — is being invited invited — was invited

has invited — has been invited should invite — should be invited

From the point of view of form the passive voice is the marked member of the opposition: its characteristic is the pattern "be + second participle", whereas the active voice is unmarked: its characteristic is the absence of that pattern.

It should be noted that some forms of the active voice find no parallel in the passive, viz. the forms of the future continuous, present perfect continuous, past perfect continuous, and future perfect continuous. Thus the forms will be inviting, has been inviting, had been inviting, and will have been inviting have nothing to correspond to them in the passive voice.

With this proviso we can state that the active and the passive constitute a complete system of oppositions within the category of voice.

The question now is, whether there are other voices in the English verb, besides active and passive. It is here that we find doubts and much controversy.

At various times, the following three voices have been suggested in addition to the two already mentioned:

- the reflexive, as in he dressed himself,

- the reciprocal, as in they greeted each other, and

- the middle voice, as in the door opened (as distinct from I opened the door).

It is evident that the problem of voice is very intimately connected with that of transitive and intransitive verbs, which has also been variously treated by different scholars. It seems now universally agreed that transitivity is not in itself a voice, so we could not speak of a "transitive voice"; the exact relation between voice and transitivity remains, however, somewhat doubtful. It is far from clear whether transitivity is a grammatical notion, or a characteristic of the lexical meaning of the verb.

In view of such constructions as he was spoken of, he was taken care of, the bed had not been slept in, etc., we should perhaps say that the vital point is the objective character of the verb, rather than its transitivity: the formation of a passive voice is possible if the verb denotes an action relating to some object.

116 The Verb: Voice

L

ast not least, we must mention another problem: what part are syntactic considerations to play in analysing the problem of voice?

ast not least, we must mention another problem: what part are syntactic considerations to play in analysing the problem of voice?Having enumerated briefly the chief difficulties in the analysis of voice in Modern English, we shall now proceed to inquire into each of these problems, trying to find objective criteria as far as this is possible, and pointing out those problems in which any solution is bound to be more or less arbitrary and none can be shown, to be the correct one by any irrefutable proofs.