Протоиерей Стефана Хедли (Франция) закон

| Вид материала | Закон |

- Содержание лекций 3-го семестра Лекция, 74.02kb.

- Протоиерей Сергей Слободской. 1993 г закон, 199.71kb.

- astike, 3450.53kb.

- Курсовая работа По дисциплине: «Страноведение» На тему: «Франция. Особенности национальной, 425.38kb.

- Протоиерей Григорий Дьяченко Борьба с грехом Благословение Свято-Троице-Серафимо-Дивеевского, 777.44kb.

- Швейцария Франция, 207.57kb.

- О командировании в Париж (Франция), 13.32kb.

- 1. Основы теории теплообмена; виды передачи теплоты; теплопроводность однослойной, 86.49kb.

- Французское искусство XII, 51.2kb.

- Протоиерей Серафим Соколов. История Христианской Церкви (начиная с 4-го века) Глава, 356.72kb.

Протоиерей Стефана Хедли (Франция)

Законодательство о религиозном образовании в европейских государственных школах

В современных европейских странах стоит вопрос о том, как объединить граждан одной нации. И религиозное образование в школах является важной гранью этого вопроса. Объединит ли оно или приведет к нетерпимости? Ослабит ли факультативное религиозное образование нетерпимость? Остановит ли веротерпимость процесс секуляризации и развитие идеологии индивидуализма? Где лучше осуществлять катехизацию: в государственных школах или в приходах и медресе?

Проблема религиозного образования имеет глобальный масштаб. В государстве Индонезия, основанном в 1949 году, вопрос его контроля стал причиной споров, как только молодая республика стала считаться светским, а не исламским государством.

Споры вокруг десекуляризации школ характерны как для России, так и Европы, поэтому естественным будет сравнение. Секуляризация в Европе почти завершена. К этому же стремятся некоторые в России, но представляют ли они, к чему может привести безразличие ценностей, как оно отразится на умах и сердцах молодежи? Результатом будет отчуждение, инфантилизм, высокое число абортов и разводов.

Сравнивая Россию с Западной Европой, нужно принять во внимание различия между странами внутри самой Европы. В некоторых странах (в Италии, Греции, Дании) религия все еще определяет нацию. В других странах (в Великобритании, Германии, Швейцарии) нормой является мультиконфессионализм, в третьей группе (в Бельгии, Испании, Турции) противостоят светские и религиозные традиции, в четвертой группе (Франция, США) религия отделена от государственного образования. В Америке созданию единого государства, как считают, послужила гражданская религия, во Франции республиканские добродетели: свобода, равенство, братство.

Другой вопрос: можно ли десекуляризовать общество сверху? В России вновь открываются церкви и изучаются основы веры, некоторые инициативы исходят от Синода и епископов. Но как к этому отнесутся в стране, пережившей 70 лет коммунизма?

В начале 90-х ожидалась иммиграция 20 млн человек из Восточной в Западную Европу. Для иммигрантов возникает проблема этнического единства. Например, католики из Ирландии в Америке пытались сохранить свою веру и столкнулись с ее американизацией. Проблема искажения религии под воздействием попкультуры актуальна и для России.

Возвращаясь к Европе, следует вспомнить, что в 19 веке религиозное образование сменилось светским, и в современных университетах появилась светская специальность «теология». 150 лет назад кардинал Ньюман, ректор Католического университета Ирландии, в своей книге «Идея Университета» пытался определить отношение либеральных искусств и теологии. Когда во второй половине 20 столетия англосаксонский мир стал размышлять о цели университетского образования, кардинала вспомнили. Где начинается отход от Бога в научных исследованиях? Экологическое движение и движение в защиту прав человека это попытка осознать природу нашей мировой солидарности.

Теперь перейдем к рассмотрению основ национальных законодательств, касающихся религиозного образования в школах. Иногда политические партии проводят законы против церкви, если считают ее слишком влиятельной. Например, в Греции правящая партия недавно провела закон, запрещающий принимать исповедь на территории школы. Это попытка соответствовать идее плюрализма, исходящей от ЕС.

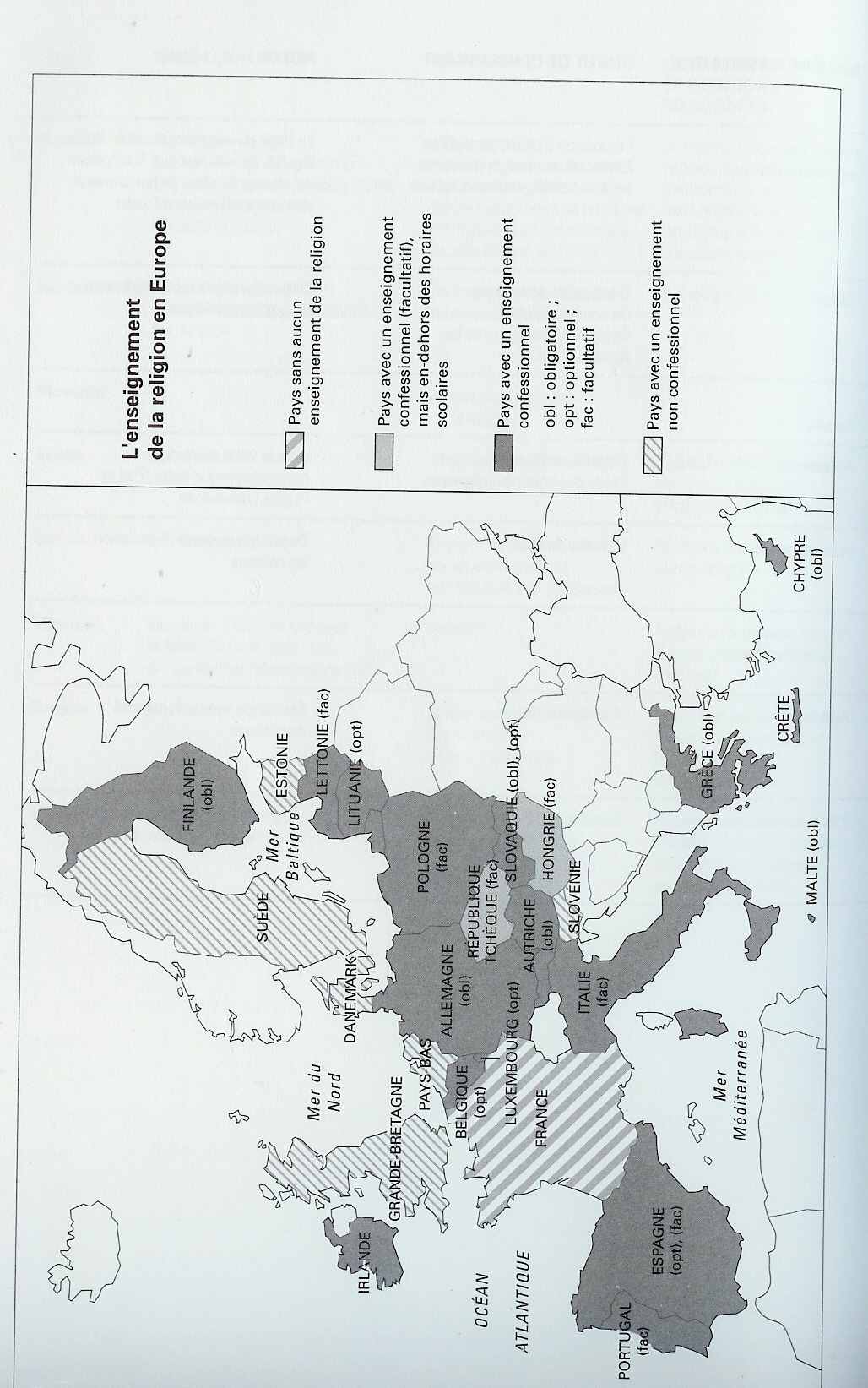

Очевидно, в Западной Европе существуют различные подходы к преподаванию основ религии, соответственно этому должно различаться законодательство. На карте рассмотрены три группы стран: страны, в которых нет религиозного образования в школах (Франция, Венгрия). Ко второй группе относятся страны, в которых неконфессиональное религиозное образование организуется и контролируется государством. Это страны северной Европы, что, вероятно, является отражением протестантского учения о том, что катехизация является обязанностью государства, и катехизация здесь обязательна. Постепенно этот вид религиозного образования подвергся секуляризации и стал неконфессиональным. Это видно на примере эволюции названия курса религиозной дисциплины в Швеции: христианское учение (1919), христианская наука (1962), наука о религии (1969), учение о жизни и существовании (1980). В Великобритании и Швеции это происходит при сотрудничестве с церквями. К третьей группе относятся страны, в которых конфессиональное вероучение утверждено законодательством (Греция, Кипр, Италия, Бельгия, Испания, Германия, Литва, Австрия, Чехия, Словакия, Венгрия, Португалия).

Европейский Союз настаивает на том, чтобы религиозное образование было факультативным. Исключением является Польша. Пример Франции, где религиозное образование отсутствует, вряд ли привлечет другие страны. В 1999 году в ответ на межрелигиозные диспуты в некоторых странах ЕС предложил в рамках рекомендации под названием «Религия и демократия» развивать неконфессиональное образование. Основные положения его следующие:

1) критически рассмотреть шкалу ценностей, чтобы согласовать этику и демократию.

2) Изучить сравнительную историю религий и обосновать их схожесть.

3) Рекомендовать религиозным учебным заведениям ввести курсы прав человека, истории, философии и других наук.

4) Беречь детей от конфликта между государственной религией и верой, исповедуемой в их семье.

Это так называемая «двойная терпимость» (неконституционно признанная религия и свобода исповедовать личную веру в определенных рамках).

Нет доказательств того, что гражданские беспорядки (расизм и нетерпимость) более характерны для стран с неконфессиональным религиозным образованием. Светская иделогия ЕС пытается утвердить мысль о том, что религия – источник нетерпимости и насилия. Например, о Греции сотрудница ЕС Лина Молокотос-Лидерман говорит так: «В этой стране религия сводится к Православию». Конечно, тем, кто считает Православие наиболее полным выражением христианства, трудно понять, что значит «сводится». Однако уже сегодня идеология индивидуализма захватывает и Грецию. Религиозное образование становится все более академическим и теряет дух катехизации. Пустеют воскресные школы. Лина Молокотос-Лидерман утверждает, что привязанность людей к определенной религии является нарушением индивидуализма. На самом деле секуляризм менее социален, чем ислам или христианство, и сознавая этот недостаток, он стал столь агрессивным в наше время.

Заключение: мы затронули два главных вопроса:

1) секуляризация Европы

2) борьба за свободу религиозного образования на государственном уровне, что рассматривается ЕС как нарушение идеологии индивидуализма.

Когда отношения между управляющим и управляемым не уравновешены третьим принципом (конституцией или божественным судом), тогда политика держится на насилии. Именно для обретения этого третьего принципа необходимо религиозное образование. Личность Христа – объект личного и коллективного опыта в большей степени, чем объект для преподавания. Если Бог непознаваем, то кто соединяет человека с Богом? Христос! Наконец, предметом катехизации является аскетическое богословие восхождения человека к Богу. Человек, умеющий молиться, не нуждается во власти, чтобы изменить государство и мир вокруг. Взяв свой крест и следуя за Христом, христиане изменяют мир. Эта истина недоступна политической науке. На самом деле власть не существует, и навязываемый ею эгоцентризм – иллюзия. Цель конфессионального религиозного образования – уберечь молодежь от этой иллюзии.

Teaching the Faith or the study of Religion?

Secularisation and intolerance in Western Europe

(draft)

Archpriest Stephan Headley

[Parish of St. Stephen the protomartyr and St. Germain d’Auxerre

Diocese of Korsoun (France), Moscow Patriarchate]

Moscow: Christmas Readings 2007:

“Truth and education: society, school and this land in the XXIst century”

Panel: “Religious factors in the formation of contemporary Society”

January 31st, 2007, Social University

Introduction: Across the Europe today countries are posing the question of how to find a unifying factor to bind the citizens of their nation together. The teaching of religion in public schools is one important facet of this issue. Will it unify the citizens in their loyalty to the state which no longer holds to any belief in God or create further conditions for intolerance amongst believers? Can the privatisation of religious education itself increase intolerance? Does favouring faith-based tolerance of others’ beliefs help neutralise secularisation and its ideology of individulism ? Is catechism narrowly defined best accomplished within the precincts of the public schools or better in the walls of the parishes and madrasah? These are complicated questions even when addressed to a specific country let alone all of eastern and western Europe.

These very questions were posed repeatedly in the Russian Federation over the last fifteen years. Recently (30.VIII.06) interfax.religi announced that a course on the Foundations of Orthodox culture will be taught in the public schools of fifteen regions in the Russian Federation. In four regions (Belgorod, Kaluga, Bryansk and Smolensk) this will be compulsory and in the other eleven regions, only upon request by the students and their parents. The teaching of the Orthodox faith in Russia requires preparing and testing different syllabi (textbooks, musical and iconographic material, pedagogical approaches); this has already begun. It also requires the training of thousands teachers; this will take longer and much of the success of the courses will depend on the quality of these teachers. In the conclusion below I will return to this basic reality that the transmission of the faith in the last analysis is a charismatic event.

One should one forget the European and global dimensions of this problem. In a new country as far away as Indonesia, founded in 1949, the question of the control of religious education has been a cause for tensions ever since the young Republic decided to consider itself a secular state rather than an Islamic one (Mujiburrhman 2006). Christians throughout the world live as religious minorities in Muslim countries are hard pressed to avoid conflict over the role of catechism in public and private schools. The success or failure of the Muslim- Christian interface in public school religious education is bound to be held up as indicative of the the ability of the Orthodox to relate to the faith of other monotheists.

Part I: The first aspect of this religious education dealt with in this short essay, is the way in which outside observers react to this important pastoral duty undertaken by different departments of the Moscow Patriarchate. Of course, media manipulation does exist Their reactions will no only be qualified by the fact that these observers are usually not Orthodox, but also by the fact that their own native countries have different legal systems reflecting very different social and economic histories. A second aspect concerning religious education in public schools concerns what can those in Russia learn from the positive and negative experiences in other countries, first of Orthodox ones.

The controversy surrounding de-secuarlisation in Russian schools (Lisovskaya and Karpaov 2005) makes Western Europe an obvious first point of comparison for the Orthodox. Despite its strong Catholic and Protestant background, Western Europe is also the most “advanced” because in these countries secularisation is almost over and the churches have lost many of their followers. This is also where some Russians want to arrive, but one wonders if they have taken into account the cost of the evaluative indifference that accompanies such secularisation and its impact on the minds and hearts of their youth. The fruits of this kind of individuation are alienation and confusion, delayed maturity and high abortion and divorce rates. Russia has already experience a great deal of this.

When comparing Russia to Western Europe , one should not underestimate the diversity of Western Europe. For some countries ( Italy, Greece, Denmark) religion still makes the nation. In other countries (Great Britain, Germany and Switzerland) mutli-confessionalism is the norm. In yet a third group of countries (Belgium, Spain and Turkey), two traditions, lay and religious, are confronting one another. Finally in a fourth and last group (France and the United States) confessional religion is banished from public education. Yet paradoxically enough in these last two countries and for diametrically opposed reasons, where religion is to be relegated to the private domain, the resulting configurations are opposite. In America it is understood that civil religion contributed in a major manner to the construction of the state, whereas in France what supposedly binds the citizens together are the “Republican” virtues of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Another issue: can one de-secularise a society top to bottom? Certainly in France after the revolution of 1789 the country was secularised top to bottom. Even if there was a counter revolution in the first half of the nineteenth century, the role of the Catholic church as an institution of meaning has been and remains drastically reduced since the French revolution. No country in Western Europe has taken de-christianisation as far (Le Goff & Rémond, eds.: Histoire de la France religieuse, vols. 3 & 4, 1992). The question is now posed in contemporary Russia, for while there is a significant ground swell re-opening churches and re-learning the rules of faith and prayer (zakon boje), nonetheless some of the initiatives also come from the Holy Synod and the bishops of the church. How will a country recovering from seventy years of Communist administration take to these ukase?

At the beginning of the 1990’s the OCDE predicted that twenty million immigrants would be arriving in Western Europe from Eastern Europe. The cultural estrangement for the Christians in this emigration cannot be underestimated. When considering religious education of immigrant communities, a further factor, is ethnic unity. An example: the immigrant Irish Catholics in America tried to preserve its faith abroad. To this end in America they developed a large parochial school system which sometimes worked at cross purposes with itself in that the rigour of much of the catechism seemed “scholastic” to the youth who were living in a post-Puritan society where the role of faith and ascetics was easily discredited. The result is well known: the discrepancy between the faith practiced back in Ireland and its Americanisation in the United States. Some would say this outcome was inevitable. A large, very diverse country, the United States, that in a Janus-faced manner has becomes both highly secularised and deeply religious. The risks for the deformation of the faith in this context are not negligible in Russia today where the pendulum effect of rampant “popular” culture is clear to everyone (Barker 1999).

Returning to Europe on the most general level, it is clear that the role of education has shifted massively, tectonically one could say, from that of teaching divine revelation to that of training in secular sciences. This shift gave rise to re-appraisal of what Christian education used to be many centuries ago: first of all in contrast to the Greek paideίa (W. Jaegar, vol. I, 1965; H-I Marrou, 1956) and secondly in the post Enlightenment “modern university”, where could one house that branch of knowledge we call theology. One hundred and fifty years ago, John Henry Cardinal Newman, then rector of the Catholic University of Ireland (1851-58), in his collected essays, The Idea of the University, tried to define the relation of the liberal arts and theology. As the Anglo-Saxon world began to doubt the purpose of the university in the second half of the twentieth century, many people returned to these reflections. Where does infidelity to God arise from in the scientific investigation and the discipline of the mind. It is not inherent to the subject matter but part of a cultural prejudice (Nestaruk 2003). Are there destructive passions released in the intellectual adventures proper to the humanities and the social sciences? The answer to those questions has come in to view not directly but tangentially. Both the ecological movement and the human rights movement in the second half of the twentieth century represent important efforts to understand the nature of our cosmic solidarity in the world created for man by God.

Having sketched out the European cultural horizon for teaching revelation in the most general terms, we can now turn to a summary of those national legislations which supposedly control the teaching of religion is public schools. Our sketch of the juridical side of the question is often anachronistic by which I mean that these laws often indicate how earlier battles where decided in parliament, but often no longer reflect the current mentality of the citizens. Nonetheless these laws do way heavily on the way teachers are allowed to behave in classrooms. Often the motivation for their updating or even their reversal are to found in propositions highlighted by the media, television, radio and the daily press which are in a position to embarrass politicians into actions for the reformation of these laws. It is also true that sometimes political parties push through legislation in order to attack their national churches they esteem too influential. Here we are dealing with a kind of law very different from God-given judgements (δikaίwμa). An example: is the recent legislation pushed through by the political party currently in power in Greece to forbid the hearing of confessions on school premises(Associated Press 12. 9.06). According to these politicians this signifies the emergence of Greece as a multicultural society, the implication being that the Greek Orthodox church by trying to control the consciences of the youth of that country in order to permit it to continue its monolithic Orthodox national heritage is contravening the evolution encouraged by the European Council to pluralism. But what is pluralism in one country is not necessarily the same as in the neighbouring nations.

Part II, the map of contemporary legislation on religious education: Clearly there are different pedagogical approaches to the teaching of religion in Western Europe, and so also there must be different juridical approaches to instituting them. The map below (p.4) summarizes Ferrari’s findings (2005:30) Three possibilities exists. Countries where no religious instruction in their schools: France is the only full example of this, although in the Czech Republic and in Hungary are resemble that situation. In the Czech republic the catechists have the status of teacher of secular subjects, while in Hungary they do not.

The second possibility is that of countries where non-confessional teaching of religion is organised and controlled by the state. With the exception of Slovenia these are all countries in northern Europe, probably reflecting the influence of Protestant ecclesiology which considered catechism to be the responsibility of the state. These courses are obligatory. Subsequently this kind of religious education came under the influence of secularism has become non-confessional. The evolution of the name of religious education courses in Sweden (Silvio Ferrari 2005:35) reflects this evolution: “the teachings of Christianity” (1919); “the science of Christianity” (1962); “the science of religion” (1969); “teachings on the question of life and existence” (1980). In Great Britain and Sweden this is done in collaboration with the churches, even if it is the state who nominates and pays these teachers of religion.

The third configuration concerns those countries where confessional teaching of religion(s) is legal. This concerns mainly countries with a strong Catholic or Orthodox presence. The following list borrowed from Silvio Ferrari (2005 30; 36-37) provides a useful summary1:

Greece & (southern) Cyprus: Orthodoxy

Italy: six religions have a concordat with the state,

but in fact only Catholicism is taught.

Belgium : six religions are recognised.

Spain: Catholicism, Protestantism, Judaism and Islam

with a concordat or entente with the state.

Germany: Catholicism, Protestantism, and in certain landers,

Judaism and Islam may be taught

Lithuania: the eight “traditional” religions may be taught.

Austria: fifteen religions are recognised and taught.

Czech Republic: in 2002, twenty-one religion were registered.

Slovakia: sixteen religions were registered in 2003.

Hungary: one hundred and fifty religions are registered but, in fact, only

Catholicism and Protestantism are taught.

Lithuania: Lutherans, Catholics, Orthodox, Baptists and Old Believers

are registered.

Portugal: Catholicism.

The difference between confessional and non-confessional teaching is currently diminishing in certain countries. Recently in Italy, Spain and Portugal the tendency has been to abandon teaching a single religion and to teach several religions. If in Germany this takes the form of ecumenical and inter-religious education, in countries like Poland and Italy where a single religion predominates, this is unlikely to occur.

The role of the European Union is presumably limited to insisting that confessional religious education be voluntary and even this rule permits exception such as Poland obtained in the European courts (1998)2. Ferrari (2005:38) claims that the French approach (no religious education) as long as it remains non-confessional will not to attract other countries. In 1999 in response to countries where inter-religious disputes have arisen the European Council’s recommendation (no. 1396) entitled “Religion and Democracy” sought to further promote non –confessional education. Its main ideas were:

(1)to associate the learning of a set of values using a critical sense in order to conjugate ethics, and democratic citizenship.

(2) to promote comparative history of religions aimed at foregrounding the similarity of these diverse traditions.

(3)to encourage religious institutions to incorporate in their courses human rights, history , philosophy and science.

(4)to avoid involving children in any conflict between the religion promoted by the state and that of their families.

One can sense the background to these proposed measures. The so-called “twin tolerations” (no constitutionally recognised religion; and freedom to practice religious privately (and even publicly) as long it interferes with no one)3. The widely held assumption that there is an inherent incompatibility between Orthodoxy on the one hand and democracy and modernity on the other is well known from the works of Samuel Huntington (1996) and Victoria Clark (2000), etc.. Russia is sometimes discounted as being more Eurasian than European and the Balkans is touted as the bastion of barbarity primarily because of religious nationalism.

These general considerations are not extraneous to the description of the debate on religious education in public schools. Although there is no proof that there is more civil disorder (racism, intolerance of whatever kind) in countries with non-confessional religious education as opposed to confessional catechism, the secular ideology of the Council of Europe predisposes it to perpetuating the prejudice that religions are sources of intolerance and violence. For instance, Lina Molokotos-Liederman (2005:71) says, speaking of Greece, “In this country the notion of religion is reduced to that of Orthodoxy.” Of course, for those who believe that Orthodoxy is the fullest expression of Christianity it is hard to understand what is meant by reduced. On the other hand, it is clear is that ethnic diasporas tend to bring their religion with them and that, qua diaspora, they find it difficult to share that religious space with anyone who is not of their ethnic group. That is not to say however that they are violent, simply that they marginalise themselves.

Greece used to recall a country where there was no religion just the custom and usages of a people. Language, music, food and religion were one; culture was indistinguishable from religion. Here the hierarchy of values religion provided what pluralism resents and considers dangerous, transmission and reproduction of social structures outside the state. But today (September, 2006) there is a gradual ground swell in the spread of the ideology of individualism amongst the Greek population. Religious education is often taught not in the spirit of a catechism in the faith, but as an academic subject, and this without the legislation have been explicitly changed to insist on this objectification of faith. The Greek Church’s Sunday schools (as opposed, to the public school’s teaching of religion), are less frequented than in the past4. Is it predetermined that the Greek Orthodox Church and the Council of Europe will continue to work at cross purposes? And as Lina Molokotos-Liederman (2005:71) point out, from the vantage point of laïcité and pluralism, any effort to encourage people to commit themselves to “their” religion is considered a violation of individualism.

The fact that from a secular point of view any theological discourse is treated as an ethnocentric one, reflects paradoxically the fact that a secularism that is ultimately more isolationalist, less social than Islam or Christianity. This reflect the atomism the ideology of individualism which has less capacity than religions to institutionalise social values. If secularism is so aggressive today, it is because it is conscious of this weakness.

Russia may prove to be a counter -example of this. Elena Losovskaya & Vyacheslav Karpov writing about religious education in Russia report that the effort to desecularise education in Russia begins in a serious way in 1992 when Asmolov the then adjunct minister of education, declared that Russian education was open to Christian values. Already in 1991 a partenariat between that ministry and the Patriarchate had been finalised.

The opponents of confessional religious education in public school have regularly stressed that the Russian Orthodox church was seeking to align itself with the Kremlin’s drift towards autocracy. But does this strident debate really hinge on the Russian government’s trying to establish its authority using that of the Church? Surely that is a useless simplification. In any given year there will be convergences and separations depending on the issues and their respective orientations. Again much depends on the prejudices with which one enters the discussion. The real problems lie elsewhere. As Lina Molokotos-Liederman (2005:71-77) says the results of confessional religious education are determined more by the quality of the manuals for religious education used and the quality of the teachers. The Greek example (a completely developed, ten-year cycle of teaching material is available) would merit careful examination. Empirically speaking, in which dioceses are the programs the most appreciated by the students, by the teachers, by the monks and priests. Participation is not to be measured in the number of years the teaching is obligatory by legislation, but rather in the evaluation of the programs by the participants. After ten years of such catechism, does one find in the environs of local higher education institutions lively Orthodox student liturgical life and discussions groups like the university parish of Hagios Panteleimon in Thessaloniki animated by a metochion of an Athonite monastery.

Conclusion: As we have suggested rapidly above the juridical legislation on the teaching of religion in public schools in Europe is the touchstone of two larger issues: (1) the on-going secularisation of Europe, which takes place in each country in a different way, and (2) the increasingly difficult struggle for the freedom to institutionalise religious practice in the public domain. The latter is treated as a violation of the ideology of individualism is by the Council of Europe. By this they really mean it is a political act for accumulating a strong social identity. Such a politicisation of our understanding of Christian social bonds contains a fallacy for such an approach ignores that there are values being circulated in society other than “power”. There is more to society than the binary relations of dominator and dominated, often characterised as “ hierarchy” by which is meant the power to control people. When ruler-ruled relationships are not mediated by a higher third principle that can be held responsible for their equilibrium (constitutions, divine judgement), what can one invoked to purify imbalances. This absence of a third principle results in the polity being held together by violence

Although such a lack of transcendence guide many, if not most Europeans today , a fundamental re-orientation towards life based on Christian revelation and the experience of prayer displays a unique kind of mediation through a third party, a highest value. It is this third transcendent party, this divine mediation that religious education is all about. We must foreground this fact in order to conclude. More than an object of teaching, the person of Christ through whom our prayer has access to the Father, is the object of personal and collective experience. The word of God is heard and not seen, felt and not touched, sensed as more intimate to me than the world itself for he is the life of the World. In Christian parlance this mediation, this hierarchy of grace, since the invention of the word by the sixth century ascetic and priest St. Dionysios, was used to describe the adequation of the love of God to each and all wherever they were between life and death.

If God is beyond knowing, who mediates between God and man? Christ! God descends to earth in the form of his Word to save and heal mankind and to deify all sense and utterance. This occurs through purification, illumination and union. Finally the object of all catechism is this ascetical theology of man’s ascent, man’s return to God. If Christ is not present in our prayer to say “amen” then we are neither free to begin it, to continue it or to conclude it (Matta el-Meskine1990:41). For this reason St. Paul (Romans 8:26) says: “Likewise the Spirit helps us in our weakness. For we do not know what we should pray for as we ought, but the Spirit himself makes intercession for us groaning that cannot be uttered.”

A person who has such a practice of prayer does not need “power” to change the state and the world around him. A Christian is aided by Christ to experience the plight of those around him and these sufferings help him to see to what extent Christ himself has suffered for the life of the world. To speak to God in prayer is to experience how the love of God displayed on the cross unites that which was separated by death and corrupted by sin. The mystery of sacrificial love takes on a meaning deeper than anything else in our lives. Our prayers a revealed capable of healing the scars on our own lives, and the poverty and sickness of those with whom we live. Our intimacy with God turns on our ability to know the burdens born by those around us. This is what Christians mean by bearing the cross God has chosen for them. By picking up his cross and following Christ, the Christians displays a manner of changing the world that is beyond the comprehension of all the political sciences whose exclusive category of reflection is that of real politik or power. In fact power is not real and the egotism it inspires, although addictive, is ultimately an illusion. The purpose of confessional religious education is fundamentally to help the youth not to fall into that delusion.

At the most general level, the role of religion in education raises issues much more important. If our Christian sociology of contemporary social issues is going to be true to revelation it must be based both on faith and on reason. By this I mean to remind ourselves that faith without reason (λόγος) makes for fanaticism, while reason separated from faith leads to atheism. The value of a Christian sociology lies in the ability of faith and reason to explain to us what is society! The word itself is an neologism belonging to the political vocabulary of eighteenth century philosophers of the nation state. Society is not a scientific concept, but an ideological one designed to promote what was then a new whole, the state, but in so doing it displaced the real whole, God , the Creator of all who “fullest all things and is everywhere present”. Are we not God’s creatures, bearing ineffaceably in ourselves his image and resemblance? The “society”, his “leviathan”, of Hobbes (1588-1679), in his struggle against divine right principles of sovereignty, forsaking any horizon of transcendence as well as the clear distinction between good and evil in public life. This “society” was the cornerstone of the enterprise of secularization, what Weber was to call some two hundred years later, disenchantment (entzauberung, from zauber, magic).

The teaching of the foundations of Orthodox culture in Russia is opposed the inheritors of Hobbes understanding of society as the brief outline above of the teaching of religion in Western public schools has suggested. The nation state cannot be the basic reference for Christians. Yet patriotism is important. How to resolve their apparent contradiction. The Patriarchate of Moscow cares for a land, a zemli. The frontiers of the Russian state change but the Patriarchate of Moscow remains because of the faithful’s shared horizon of transcendence, what in the prayers of the Church is called God’s sacrificial love!

If the whole is God hen Christian patriots do not seek power (vlast) which can be seized by any one, but seek to acquire spiritual authority which can only be given us by sacrifice, and faithfulness to God’s truth. We can only enter public school to teach the foundations of Orthodox culture because we have received the gift of truth through baptism and holy communion. …because we know that it is God who is the whole and not society.

[insert here Appendix 1: ]

OLIR “L’Insegnamento religioso nelle scuole pubbliche Europee”]

___________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Anastassiadis, Anatassios

« Religion and Politics in Greece : the Greek Church’s ‘Conservative Modernisation’ in the 1990’s », p. 17-18, Research in Question no. 11 (January 2004), CERI, Scinces Po, Paris.

Barker, Adele Marie (ed.)

1999 Consuming Russia. Popular culture, sex and society since Gorbachrev. Durham, Duke University Press.

Clark, Victoria

Why angels Fall: a journey through Orthodox Europe from Byzantium to Kosovo. New York, St. Martin’s Press.

Ferrari, Silvio

2005. « L’enseignement des religions en Europe : un aperçu juridique » pp. 31-40in Willaime, Jean Paul with Mathieu, Séverine (editors), Des Maîtres et des Dieux : écoles et religions en Europe. Paris, Belin.

Huntington, Samuel

1996 The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of the World Order. New York, Simon and Schuster.

Jaeger, Werner

1939. Paideia : The Ideals of Greek Culture. Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Le Goff, Jacques & Rémond, Réné (editors)

1992. L’Histoire de la France Religieuse. Vols. 3 & 4. Paris, Seuil

Lisovskaya, Elena & Karpov, Vyasheslav

2005. « La religion dans les écoles russes : une désecularisation contestée. » pp. 181-192 in Willaime, Jean Paul with Mathieu, Séverine (editors). Des Maîtres et des Dieux : écoles et religions en Europe. Paris, Belin.

Marrou, H.I.

1964 (French edition 1948) A History of Education in Antiquity. New York, Mentor Book..

Matta el-Meskine

1990 Prière, Esprit Saint et Unité Chrétienne. Bégrolles-en –Mauges, Abbaye de Bellefontaine.

Mujiburrahman

- Feeling Threatened. Muslim – Christian Relations in Indonesia’s New Order. PhD thesis Utrecht University.

Nestaruk, Alexei V.

2003 Light from the East. Theology, Science and the Eastern Orthodox Tradition. Minneapolis, Fortress Press.

Newman, John Henry Cardinal

1959 (reprint). The Idea of the University. New York, Image Books

Prodromou, Elizabeth

Date? “Orthodox Christianity, Democracy and Multiple Modernities” (especially the bibliography) at WWW.goarch.org/en

Willaime, Jean Paul with Mathieu, Séverine (editors)

2005. Des Maîtres et des Dieux : écoles et religions en Europe. Paris, Belin.

____________________________________________________________________

1 For the year 2005 Alberto Pisci provides (cf .below Appendix I) a complete four page summary table at : ссылка скрыта . For a six-page French language version incorporating the data of Flavio Pajer’s « Sculoa et instruizione religiosa » Nuova cittadinanza europea in Il Regno –Attialità, (22/2002 :776 ), cf. Séverine Mathieu, « Tableau. l’enseignement relatif aux religions en Europe » pp.24-29 in Willaime, Jean Paul with Mathieu, Séverine (editors). Des Maîtres et des Dieux : écoles et religions en Europe. Paris, Belin.

2 . Obviously this role is changing in time, cf. the recommendation number 1720 Education et Religion, submitted by M. André Schneider in the spring of 2005 (cf. the website of the Council of Europe (ссылка скрыта) and the report in the European Forum News, no. 4 2005)

3 Cf. Elizabeth Prodromou, “Orthodox Christianity, Democracy and Multiple Modernities” (especially the bibliography) at WWW.goarch.org/en . Obviously where churches carry out coronation it is implied that the state and the church have good reasons to collaborate.

4 Almost 25% decline from 1980-1990. Cf. the Diptych of the Church of Greece cited in Anatassios Anstassiadis, « Religion and Politics in Greece : the Greek Church’s ‘Conservative Modernisation’ in the 1990’s », p. 17-18, Research in Question no. 11 (January 2004), CERI, Sciences Po, Paris.