Railway and Electricity Restructuring in Russia: On the Road to … Where

| Вид материала | Документы |

- Japan International Medical Symposium, Irkutsk, Russia, September 3 1996. P. 78 Поспелов, 18.5kb.

- Dollar Thrifty Russia объявляет победителя в конкурс, 41.59kb.

- Printing Solutions Russia, 1с-битрикс, Ледас 10: 30-12: 00 Торжественное вручение диплом, 135.34kb.

- Премия «Читай Россию/Read Russia» за лучший перевод произведений русской литературы, 18.04kb.

- The West Coast Railway Association (wcra) is a non-profit society incorporated in 1961, 47.88kb.

- Новые автомобили Fiat Albea в компании Dollar Thrifty Russia!, 88.3kb.

- 1. ао «Казахстанская компания по управлению электрическими сетями» (Kazakhstan Electricity, 243.17kb.

- Международная выставка-конференция EduTech Russia 2011, 26.95kb.

- Пресс-релиз Крупнейшая технологическая конференция Microsoft в России Tech∙Ed Russia, 236.2kb.

- Основные направления дискуссий, 573.1kb.

Russell Pittman

Railway and Electricity Restructuring in Russia: On the Road to … Where?

Restructuring the old infrastructure sector enterprises has become a thriving activity throughout the world over the past few decades. Technological advances have made it possible for the sectors once considered to be “natural monopolies” to be opened up in a variety of ways to entry and competition, and experience has convinced economists and policy makers that such entry and competition are often better mechanisms than government ownership or regulation for ensuring high quality service and protecting the public from the abuses of monopolies. The potential for some competition seems to exist in each of the old natural monopoly sectors: for multiple companies to generate electricity; to explore for and produce natural gas; to provide internet, mobile, long distance, and other telecommunications services; to run trains; even to purify drinking water.1

Unfortunately, however, these developments have generally not removed all concerns about natural monopoly from these sectors. While each of these sectors has seen improved possibilities for the introduction of competition, each also contains “network” or “grid” activities that retain certain natural monopoly elements: the long distance transmission lines and local distribution lines in electricity; natural gas pipelines; the local fixed wire “loop” in telecommunications; railway track, signaling, and station infrastructure; and the water pipe network.

This interface of potentially competitive “supply” activities with a natural monopoly “grid” raises difficult questions for reformers – questions that, I would argue, have so far eluded broad, definitive answers. Most importantly, and what will be the focus here: Should the enterprise operating the grid participate in the competitive supply activities as well? For example, in Russia, should the operator of the rail network, RZhD, also operate trains? Should the operator of the electricity network, the Federal Grid Company, also generate electricity?2

The majority of economists and reformers who have addressed this broad question have come down on the negative side. The thinking has been that a grid operator ordered to allow access to the network on regulated terms will often have incentives to provide superior service terms to its partner supply enterprise and correspondingly inferior service terms to independent, non-affiliated supply enterprises, and that as a result true competition will never appear in the supply portion of the sector. This is considered to be an especially important concern in countries like Russia that lack a strong regulatory and legal infrastructure for controlling the behavior of enterprises as powerful as RAO UES and RZhD.

An early and clear example of this policy view at work is in the famous U.S. v. AT&T case. The old “Bell system” had been a vertically integrated natural monopoly telecommunications system, with Bell Telephone providing local telephone service through its systems of local wires as well as long distance service through its nationwide system of long distance wires. With the development of microwave technology, new companies like MCI were able to compete with Bell to provide long distance service to both homes and enterprises, but to compete effectively these companies needed access to the local network – which Bell, their competitor in the provision of long distance service, controlled. Despite extensive efforts by the national regulator, the Federal Communications Commission, Bell continued to provide (allegedly) inferior access terms and conditions to these independent long distance companies as compared to those provided to its own long distance operations. Finally the Department of Justice brought a lawsuit under the Sherman Act, claiming that Bell was abusing its dominant position (“monopolizing”, in the terminology of the Sherman Act), and under the terms of the settlement of this lawsuit Bell/AT&T withdrew from the provision of local telephone service.3

This policy option of requiring the grid operating company to exit from the provision of upstream services – generally termed “vertical separation” – is widely but not universally accepted as the preferred restructuring plan for the old infrastructure sector enterprises. The principal alternative option – preferred by some as a broad default strategy, accepted by most as superior in at least some circumstances – is to allow the grid operating company to provide upstream services itself, but also to require it to provide access to the grid to its upstream competitors under nondiscriminatory terms – the same path that was pursued in U.S. telecommunications after MCI entry but before AT&T dissolution. This alternative option is generally termed “third party access” (TPA) or “mandatory access”.

TPA may have a number of advantages over vertical separation in particular situations. Most important is probably the maintaining of economies of vertical integration: in rail and electricity as well as other sectors, there may be difficult issues of coordination to resolve if multiple service providers are to have access to the grid.4 But there are other concerns as well:

- If there are economies of scale in upstream supply – e.g. electricity generation or train operation – vertical separation may simply replace a vertically integrated monopoly with something close to vertically separated bilateral monopoly.

- Vertical separation introduces a number of complex questions involving the calculation of “access prices” for the use of the grid. TPA in turn renders these questions both more complex and more crucial.5

- Vertical separation seems to make it much more difficult for a grid operator to receive good signals and incentives for decisions regarding grid investments. Since grids are by definition capital intensive, poor signals regarding investments may be especially important and harmful.

Though most discussions of natural monopolies restructuring, especially in Europe, focus on the relative advantages of vertical separation and TPA, in fact there are further alternative strategies as well. In the railroad sector in particular, most countries in the Western Hemisphere have eschewed both vertical separation and TPS in favor of what we might call “horizontal separation” – relying on competition among vertically integrated railway enterprises, each with some regional exclusivity but competing both over some parallel routes and at some common points.6 For example, the old vertically integrated monopoly Mexican railway was restructured horizontally, with three vertically integrated private enterprises (with long-term franchises rather than full ownership of the infrastructure) serving all shippers in Mexico City and competing at a few other common points as well. (See Figure 1.) Also for example, in the late 19th century, vertically integrated, privately owned railways competed for business in Russia, and the beneficial effects of this competition for customers like the grain shippers of the Black Earth region, who could choose between railways shipping north to the Baltic Sea and south to the Black Sea, has been well documented.7 (See Figure 2.)

Russia has so far pursued different restructuring strategies between the rail sector and the electricity sector – TPA in the former and vertical separation in the latter – though both sectors are in some flux, and their ultimate form of organization is not completely clear.

Russian railways restructuring8

The Russian railway sector is in the third stage of a three-stage restructuring plan. The first stage was devoted to creating a (government owned) joint stock company – replacing the ministry of railways, MPS, with the Russian Railways Company, RZhD. This stage was completed swiftly and successfully. The second stage was to encompass mainly the separation of noncore activities and the elimination of a complex system of cross-subsidies, including both freight-to-passenger and within-freight. The former task is generally complete, but the latter still has far to go: despite repeated hopeful statements to the contrary, the regions have not yet agreed to take over the subsidization of regional passenger operations, and most analysts believe that some long distance freight moves – especially coal moving west from Siberia to European Russia – travel at tariffs below variable cost.

It was in the third stage that competition for freight operations was to be created within the system. Initially this competition was to take the form of TPA; there is controversy over whether, even by design, the ultimate goal was vertical separation. (Reformers such as MEDT Minister German Gref, Transport Minister Igor Levitan, and Director of the Federal Antimonopoly Service Igor Artemiev have said yes; RZhD President Vladimir Yakunin and his predecessor Gennady Fadeyev have said no.) In any case, the creation of competition under a TPA regime has been so slow as to be negligible, for reasons that come as no surprise to those expecting discrimination by a vertically integrated infrastructure and services provider against a non-integrated services provider:

- Until recently the legislation providing for the issuance of infrastructure access permits to companies other than RZhD was not in place, and the few independent train “operators” on the system were thus lacking formal permits to be there.

- Uniquely in the world, the restructuring legislation requires that any independent train operators serve as what are called in the US “common carriers” – i.e. that they be able to provide service to shippers of any commodity in any location in the Russian Federation.

- Access charges for independent train operators are extraordinarily high, averaging about 55 percent of regulated cargo tariffs – certainly the highest rail infrastructure access charges in the world.

What may serve as the coup de grâce for the creation of above-the-rail freight competition in Russia, however, has taken place only within the past year or two. RZhD apparently had only one reason to continue to pursue reforms and the creation of competition: RZhD tariffs are regulated, and individual tariffs can be deregulated only upon the demonstration of the existence of competition in particular circumstances. On the other hand, the tariffs of independent train operators are not regulated, and motor carrier tariffs are also not regulated. Since the regulated tariffs include the cross-subsidies mentioned above, RZhD faced at least the theoretical possibility of losing some of its higher paying hauls to the “cherry picking” of unregulated train operating and motor freight companies.

In the past couple of years, however, RZhD has overseen the creation of four “daughter companies” – train operating companies legally separate from RZhD but partially or completely owned by them. These include Transcontainer, for container service; RefService, for refrigerated cargoes; Russkaya Troika, focusing on traffic on the Trans-Siberian Railway; and a New Cargo Company, which will carry coal and other bulk commodities. (In addition there are reports and discussions of future daughter companies specializing in timber and lumber and in autos.) RZhD claims that as these daughter companies are organizationally separate from RZhD itself they are not restricted to charging the tariff levels that are obligated for RZhD, and – surprisingly, to a US observer – the regulators and the Federal Antimonopoly Service seem to agree. If this situation remains unchanged, it seems likely that more and more of the trains that run on the RZhD infrastructure will be those of the daughter companies rather than of RZhD itself, that legislation and regulations unfriendly to independent train operating companies will remain in place, and RZhD and its daughter companies will continue to carry almost all the rail freight in Russia.

There is, or at least was, a possible alternative strategy for the creation of competition on the Russian railway. The original three-stage reform plan of the government called for the consideration of creating competing vertically integrated railways – along the lines of the Mexican restructuring plan discussed earlier – and there was apparently some discussion of the pursuing the horizontal separation option in European Russia. I was part of a group that proposed a rough plan for such a restructuring, one that would have created parallel competition from Moscow to the connection to the Trans-Siberian Railway at Omsk, and competition for customers in Moscow from competing railways radiating from the city in different directions.9 (See Figure 3.) However, there is no indication that such a plan is under any serious consideration at this point.

A recent statement from RZhD President Vladimir Yakunin is not particularly reassuring on the competition issue. He told RZhD-Partner International Magazine, “During the third reform stage, which we have just entered, we would like to have all the necessary legal, economic and technological conditions in place in order to assure competitiveness. And after that we will evaluate and make a decision regarding the possible emergence of alternative railway carriers to OAO RZD.” So it seems that no one – other than shippers, perhaps – is in a great hurry.

Russian electricity sector restructuring10

Unlike the railways sector, the electricity sector in Russia is currently in the process of complete vertical separation. The generation system is in the process of being restructured into six interregional generation companies (OGKs) and fourteen territorial generation companies (TGKs), all to be sold to the private sector, in addition to separate government owned companies providing nuclear and hydro generation. (The OGK and TGK generation plants are mostly thermal powered, though there are a few hydro plants in the mix.) A separate, government owned Federal Grid Company will then deliver the power generated by these firms to separate regional distribution companies. Wholesale generation prices are gradually to be liberalized, with a goal of 100 percent price liberalization by 2011. Wholesale generation markets are to be protected from anticompetitive behavior by a ceiling of 35 percent on the share of generation in any “price zone” by a single generation company.

There is reason to be concerned, however, about the level of market power that may be present in individual regional generation markets following restructuring. The experience to date with vertical separation in electricity markets – for example, in the UK and in California – makes clear some distinctive features about the electricity sector that may complicate restructuring initiatives that seek to introduce competition in wholesale generation markets. Among the most important of these are the following:

- Non-storability of the product, so that demand and supply must be equalized at every moment;

- Inelasticity of short-term demand in response to prices that may vary a great deal from hour to hour;

- A sometimes large portion of supply that is supplied by baseload technologies (such as nuclear and coal) whose supply is likewise inelastic with respect to price; and

- Inelasticity of overall market supply as capacity limits are neared.

The combination of these factors has tended to make wholesale generation markets vulnerable to anticompetitive behavior on the part of generation companies, especially those controlling the output of multiple plants at diverse points on the supply curve (who are able to earn extra profits on the output of their “inframarginal” plants by restricting output in their marginal plants). It has also meant that generation markets whose structure appears to be competitive using the standard tools of industrial economics and competition law enforcement – for example, concentration ratios and Herfindahl-Hirschman indexes – may not be so competitive in practice.11

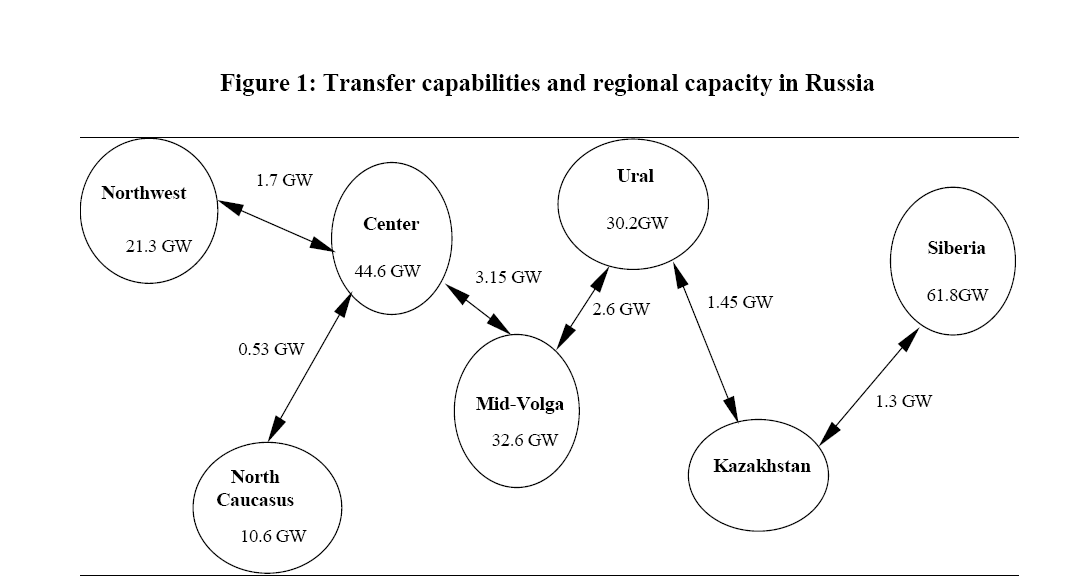

In addition, there a number of factors more specific to the Russian (though not only the Russian) electricity sector that are relevant for an analysis of wholesale competition following vertical separation. First of all, long distance inter-regional transmission capacities are limited, thus rendering it difficult or impossible for distant generators to shift supply into regions experiencing price spikes. Figure 4 shows the “dispatching areas” traditionally used by RAO UES and considered by many analysts as rough approximations of what regional wholesale markets might develop following restructuring, while Figure 5 shows estimates of the limited transmission capacity between these areas. (Unfortunately it appears that “price zones” in which there will be a 35 percent ceiling on any single generation company’s share of production are to be much larger than these approximations of regional markets; apparently all of Russia west of the Urals Mountains constitutes one such price zone.)

Second, close to 20 percent of Russia’s electricity generation is coal-fired, and, as mentioned earlier, much of the coal powering this generation travels west from Siberia at subsidized rail tariffs; as the rail sector becomes less regulated, those tariffs are expected to increase. (There are related worries about future increases in the price of natural gas.) Third, Russian electricity demand has a winter peak. This is important first of all because hydro supplies may be severely reduced in the winter, a fact not reflected in annual averages of capacity and production. It is even more important because a large proportion of Russia’s gas-fired plants are combined heat and power (CHP) plants. Gas-fired generation plants are relied upon throughout the world to provide supply flexibility in response to electricity price, but gas-fired plants that must run throughout the winter will not exhibit such supply flexibility.

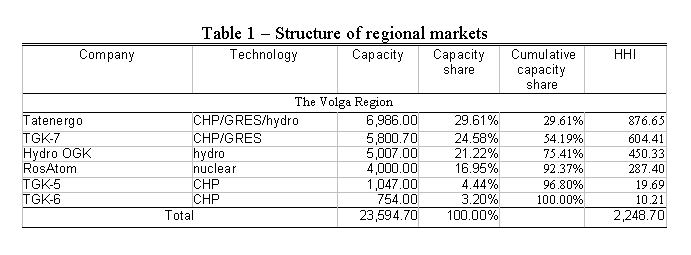

This combination of factors specific to Russia seems likely to render regional wholesale electricity markets quite inflexible under conditions of peak demand – and thus subject to very large wholesale price increases. Figures 6, 7, and 8 provide a demonstration for the post-reform Volga region. As Figure 6 shows, the wholesale electricity market as designed under current restructuring plans is fairly concentrated: there are only six firms; two of these are publicly owned firms, whose responsiveness to price signals is difficult to predict; and the top two firms, Tatenergo and TGK-7, control just over half of generation capacity.

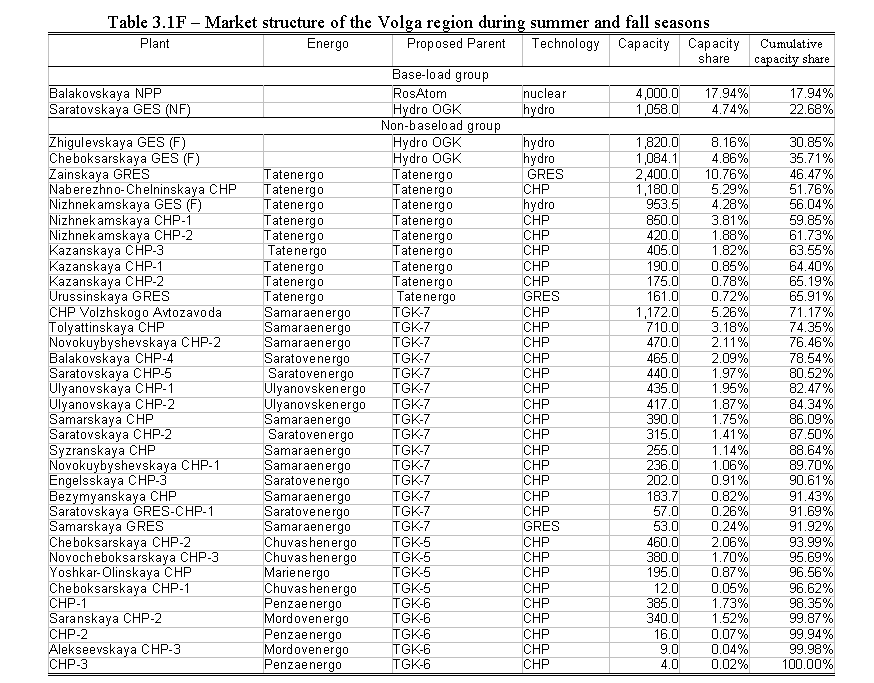

Figures 7 and 8 demonstrate the importance of examining the situation for different seasons of the year, and the great importance of the inflexibility of production exhibited by CHP plants in the winter. What is important here is not the detail but the larger picture. In particular, note that in the summer and fall seasons (Figure 7), only two generation plants, accounting for less than 25 percent of capacity, are classed as baseload; all the rest seem likely to have the ability to exhibit some flexibility in response to wholesale price signals. This does not improve the fairly concentrated structure suggested by Figure 6, but at least it does not make it appear any worse.

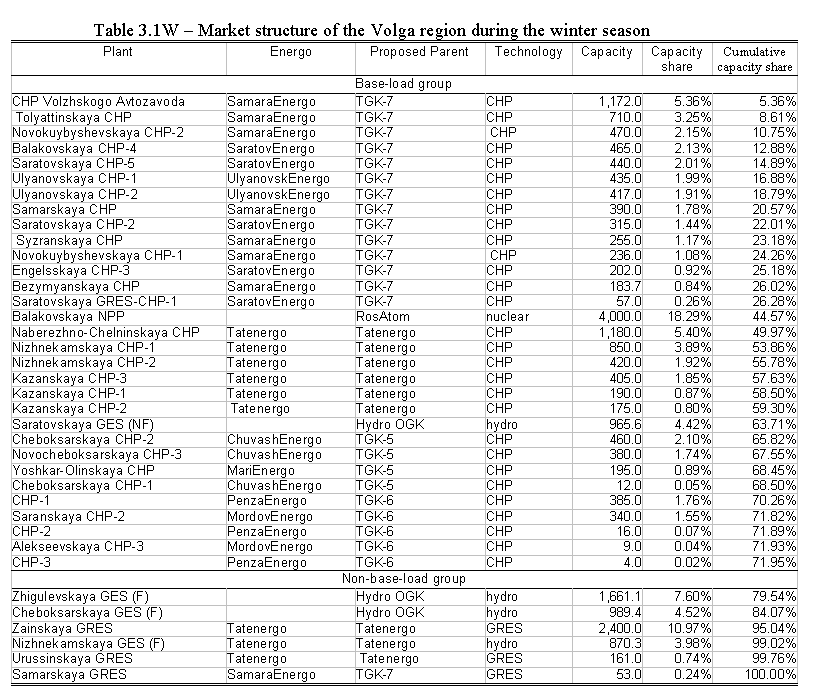

The same cannot be said for the situation in the winter (Figure 8). With the seasonal reallocation of the CHP plants from non-baseload to baseload, now about 72 percent of generation capacity is baseload, i.e. inflexible in response to wholesale price signals. Another 12 percent is represented by the large Zhigulevskaya and Cheboksarskaya hydro complexes that will belong to the government-owned Hydro OGK; again, the degree of price flexibility to be exhibited by government-owned generation facilities remains to be seen. The only remaining non-baseload capacity consists of three Tatenergo plants – the large thermal Nizhnekamskaya plant, the moderate sized Nizhnekamskaya hydro complex, and the small Urussinskaya thermal plant – and the small thermal Samarskaya plant of TGK-7. To the degree that one can even speak of a wholesale electricity “market” under such circumstances, it is not likely to be a competitive one.

I have focused here on the region with the competitive problems that appear most serious. However, similar problems – especially those associated with a loss of price sensitivity in the winter – are present in other regions as well. In particular, the Central, Northwest, and Siberia regions all display quite concentrated non-baseload capacity in the winter season, and the South joins this group if one forecasts inflexible behavior on the part of the government-owned Hydro OGK. Finally, all of these analyses and forecasts assume that wholesale power will move freely across an entire “region”, as defined by RAO UES. Experience in other countries, including the US, suggests that at times of peak demand there may be “bottlenecks” of congestion at particular points on transmission lines that reduce the magnitude of geographic markets below that of these regions – and hence may exacerbate problems of localized monopoly power.12

In sum, there are certain difficulties, even contradictions, that appear to confront Russia and the Russian electricity sector as reforms and restructuring continue. There is a widespread agreement that the system requires very large new commitments of investment capital, especially for new generation capacity and increased and more reliable long distance transmission capacity. There is an agreement that the private sector is likely to be the appropriate source for this increased investment. At the same time, there are serious doubts about the abilities of policy makers to increase user prices to levels that would support these investments – plans and expectations for full deregulation of wholesale electricity prices by 2011 are accompanied by expectations that household prices will be regulated beyond that date, and perhaps far beyond it.13 Other analysts point to not only political constraints but also the system-wide economic impacts of significant increases in energy prices.14

And these problems are in addition to the problems of market power that I have identified and discussed here. Regarding the latter issues, it is difficult to disagree with the recent statement of RAO UES president A. Chubais concerning the restructuring process: “I have ambivalent feelings about this. As CEO of the company, I have to attract investors and create favorable conditions for investment to come into the sector. But as an independent analyst of the energy sector, I feel some concerns about monopolism in the power sector.”15

References

Blumstein, C., L.S. Friedman, and R. Green, “The History of Electricity Restructuring in California,” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 2 (2002), 9-38.

Brennan, Timothy J., “Why Regulated Firms Should Be Kept Out of Unregulated Markets: Understanding the Divestiture in United States v. AT&T,” Antitrust Bulletin 32 (1987), 741-793.

Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics, Rail Infrastructure Pricing: Principles and Practice (Canberra: Australian Department of Transport and Regional Services, 2003).

European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Regulatory Reform of Railways in Russia (Paris, 2004).

European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Railway Reform and Charges for the Use of Infrastructure (Paris: 2005).

Friebel, Guido, Sergei Guriev, Russell Pittman, Elizaveta Shevyakhova, and Anna Tomova, “Railroad Restructuring in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe: One Solution for All Problems?”, Transport Reviews 27 (2007), 251-271.

International Energy Agency, Russian Electricity Reform: Emerging Challenges and Opportunities (Paris, 2005).

Joskow, Paul, “California’s Electricity Crisis,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy (2001).

Katyshev, P.K., E. Yu. Maruhkevich, S. Ya. Chernavsky, and O.A. Eismont, “Influence of Natural Monopolies’ Tariffs on Russian Economy,” paper presented at the Higher School of Economics conference, Moscow, April 2007.

Newbery, David, Privatization, Restructuring, and Regulation of Network Utilities (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999).

Pittman, Russell, “Vertical Restructuring (or Not) of the Infrastructure Sectors of Transition Economies,” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 3 (2003), 5-26.

Pittman, “Russian Railways Reform and the Problem of Non-Discriminatory Access to Infrastructure,” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 75 (2004), 167-192.

Pittman, “Chinese Railway Reform and Competition: Lessons from the Experience in Other Countries,” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 38 (2004), 309-332.

Pittman, “Restructuring the Russian electricity sector: Re-creating California?”, Energy Policy 35 (2007), 1872-1883.

Pittman, “Options for Restructuring the State-Owned Monopoly Railway,” in Scott Dennis and Wayne Talley, eds., Railroad Economics (Research in Transportation Economics, v. 20) (New York: Elsevier, 2007).

Pittman, “Make or buy on the Russian railway? Coase, Williamson, and Tsar Nicholas II,” Economic Change and Restructuring 40 (2007), forthcoming.

Pittman, Oana Diaconu, Emanual Sip, Anna Tomova, and Jerzy Wronka, “Competition in Freight Railways: ‘Above-the-Rail’ Operators in Central Europe and Russia,” Journal of Competition Law and Economics 3 (2007), forthcoming.

U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division, Competitive Impact Statement in U.S. v. Exelon, ссылка скрыта

Figure 1. Mexican Railway System

Figure 2. Russian railways, late 19th century. Source: J.N. Westwood, History of Russian Railways (London: 1964); ellipse noting Black Earth region added.

Figure 3. One plan for vertically integrated and competing railways in European Russia. Source: Sergei Guriev, Russell Pittman, and Elizaveta Shevyakhova, “Competition vs. Regulation: A Proposal for Railroad Restructuring in Russia in 2006-2010,” working paper, Centre for Economic and Financial Research, Moscow, 2003; and Friebel, et al., supra note 8.

Figure 4. Russian wholesale electricity “dispatching areas”. Source: RAO UES.

Figure 5. Inter-regional transmission capacities. Source: Alexander Abolmasov and Denis Kolodin, “Market Power and Power Markets: Structural Problems of Russian Wholesale Electricity Market,” working paper, Economics Education and Research Consortium (Moscow), May 2002.

Figure 6. Summary of Structure of Wholesale Electricity Market in Volga Region. Source: Russell Pittman, “Restructuring the Russian electricity sector: Re-creating California?”, Energy Policy 35 (2007), 1872-1883.

Figure 7. Detail of Structure of Wholesale Electricity Market in Volga Region in Summer and Fall Seasons. Source: Russell Pittman, “Restructuring the Russian electricity sector: Re-creating California?”, Energy Policy 35 (2007), 1872-1883.

Figure 8. Detail of Structure of Wholesale Electricity Market in Volga Region in Winter Season. Source: Russell Pittman, “Restructuring the Russian electricity sector: Re-creating California?”, Energy Policy 35 (2007), 1872-1883.

1 Detailed discussions are available in, for example, David Newbery, Privatization, Restructuring, and Regulation of Network Utilities (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1999), or Russell Pittman, “Vertical Restructuring (or Not) of the Infrastructure Sectors of Transition Economies,” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 3 (2003), 5-26.

2 I do not address here the issue of whether the grid operator should be privatized, or should be opened to private sector participation – though this issue has obvious relevance for the incentives of the operator.

3 A valuable discussion of this case is Timothy J. Brennan, “Why Regulated Firms Should Be Kept Out of Unregulated Markets: Understanding the Divestiture in United States v. AT&T,” Antitrust Bulletin 32 (1987), 741-793.

4 Indeed the early UK and US railroads were designed to be open to multiple train operating companies, but the replacement of horse-drawn wagons with locomotives rendered this option too difficult (and dangerous) to continue.

5 Bureau of Transport and Regional Economics, Rail Infrastructure Pricing: Principles and Practice (Canberra: Australian Department of Transport and Regional Services, 2003); Russell Pittman, “Russian Railways Reform and the Problem of Non-Discriminatory Access to Infrastructure,” Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics 75 (2004), 167-192; European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Railway Reform and Charges for the Use of Infrastructure (Paris: 2005).

6 Russell Pittman, “Chinese Railway Reform and Competition: Lessons from the Experience in Other Countries,” Journal of Transport Economics and Policy 38 (2004), 309-332; Pittman, “Options for Restructuring the State-Owned Monopoly Railway,” in Scott Dennis and Wayne Talley, eds., Railraod Economics (Research in Transportation Economics, v. 20) (New York: Elsevier, 2007).

7 Russell Pittman, “Make or buy on the Russian railway? Coase, Williamson, and Tsar Nicholas II,” Economic Change and Restructuring 40 (2007), forthcoming.

8 For more details, see European Conference of Ministers of Transport, Regulatory Reform of Railways in Russia (Paris, 2004); Guido Friebel, Sergei Guriev, Russell Pittman, Elizaveta Shevyakhova, and Anna Tomova, “Railroad Restructuring in Russia and Central and Eastern Europe: One Solution for All Problems?”, Transport Reviews 27 (2007), 251-271; and Russell Pittman, Oana Diaconu, Emanual Sip, Anna Tomova, and Jerzy Wronka, “Competition in Freight Railways: ‘Above-the-Rail’ Operators in Central Europe and Russia,” Journal of Competition Law and Economics 3 (2007), forthcoming.

9 We made no claims of great originality for this plan. We understand that the late Jane Holt of the World Bank had proposed similar restructuring models in the 1990s.

10 For more details, see International Energy Agency, Russian Electricity Reform: Emerging Challenges and Opportunities (Paris, 2005) and Russell Pittman, “Restructuring the Russian electricity sector: Re-creating California?”, Energy Policy 35 (2007), 1872-1883.

11 See the papers cited in Pittman, ibid., on the experiences in the UK and California, especially Paul Joskow, “California’s Electricity Crisis,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy (2001), and C. Blumstein, L.S. Friedman, and R. Green, “The History of Electricity Restructuring in California,” Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade 2 (2002), 9-38.

12 For a recent US example, see the Competitive Impact Statement filed by the Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice in U.S. v. Exelon, at ссылка скрыта .

13 See, for example, “Russian government to liberalise electricity market in 5 years,” Itar-Tass, December 13, 2006, and Graham Stack, “Lighting Up Europe,” Moscow Times, October 22, 2007.

14 P.K. Katyshev, E. Yu. Maruhkevich, S. Ya. Chernavsky, and O.A. Eismont, “Influence of Natural Monopolies’ Tariffs on Russian Economy,” paper presented at the Higher School of Economics conference, Moscow, April 2007.

15 Rebecca Bream, “UES head casts light on his uphill task,” Financial Times, September 11, 2007.