Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture across History Учебное пособие

| Вид материала | Учебное пособие |

СодержаниеJohn Donne For Whom the Bell Tolls Childhood and youth The Horn-Book Starting a career in London Romeo and Juliet Julius Caesar |

- Е. В. Воевода английский язык великобритания: история и культура Great Britain: Culture, 365.14kb.

- Курс лекций по дисциплине английский язык Факультет: социальный, 440.82kb.

- Учебное пособие соответствует государственному стандарту направления «Английский язык», 2253.16kb.

- Lesson one text: a glimpse of London. Grammar, 3079.18kb.

- Реферат по дисциплине: страноведение на тему: «The geographical location of the United, 1698.81kb.

- Education in great britain, 98.44kb.

- The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 257.28kb.

- Г. В. Плеханова английский язык учебно-методическое пособие, 1565.3kb.

- А. Л. Пумпянский написал серию из трех книг по переводу, 3583.47kb.

- Учебное пособие для студентов факультета иностранных языков / Сост. Н. В. Дороднева,, 393.39kb.

- John Donne

The Elizabethan Age produced a poet whose works were fully appreciated only in the 20th century, who seems to be the product of the Atomic Age. John Donne (1573-1631) started as ‘Jack Donne’, a soldier, lover, drinker, writer of passionate amorous verses. He ended as Doctor John Donne, bishop, Dean of St. Paul’s, great preacher and one of the most respected men in the country. And yet these two extremes coexisted in him all his life. As a passionate lover, he was always analytic and thoughtful, tryoing to explain his passion almost scientifically. As a priest, he addressed God with the fierceness of a lover. Donne invented many new verse forms of his own.

In his poetry, which reflects his character, extremes meet. When his passion is most physical, he expresses it most intellectually. He is always startling and always curiously modern. It is from his poem For Whom the Bell Tolls that E. Hemingway borrowed the title for his novel.

| DO YOU KNOW THAT | |

| ? |

LECTURE 5

T

1. The first playhouses

he Elizabethans created an elaborate system of activities and events to keep themselves entertained. One of the favourite entertainments was watching theatrical performances. Since ancient times there existed two principle stages on which dramatic art developed in Europe. These were the church and the market place. In the 15th century, the plays called moralities, were sometimes acted even in town halls. Church performances of mysteries and miracles were directed by priests and acted by the boys of the choir. Since then, it became a long-time tradition to have only men-actors on the English stage.

At the time of Henry VIII, when Protestants drove actors out of the church, acting became a profession in itself. As soon as people heard the sounds of a trumpet announcing the beginning of a play, they would run in crowds to the inn-court which served as an improvised stage. Indeed, an inn-court was best suited for the purpose, with its large open court surrounded by galleries. In the middle of the yard, actors put up a platform with dressing-rooms at the back. The so-called ‘clean’ public sat in the galleries which later came to be known as ‘boxes’, some even sat on the stage. The poorer spectators stood in front of the stage, in the stalls. To make the audience pay for the entertainment, the actors took advantage of the most thrilling moment in the plot and sent a hat round for a collection.

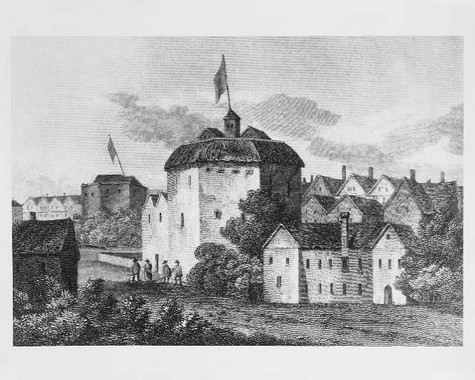

The development of drama in England was closely connected with the development of the theatre. From the very beginning, the regular drama was divided into comedy and tragedy. Most companies of players had their own playwrights who were also actors. As plays became more complicated, there appeared special playhouses. The first regular p

layhouse in London appeared on the premises of the former Blackfriars Monastery where miracles had been performed even before the Reformation. That playhouse was built in 1576 by the actor James Burbage who called it The Theatre. The Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse located in Shoreditch, just outside the City of London. The Theatre is considered to have been the first playhouse built in London for the sole purpose of theatrical productions. The Theatre's history includes a number of important acting troupes including the Lord Chamberlain's Men which employed Shakespeare as actor and playwright. After a dispute with the landlord, the theatre was dismantled and the timbers were used in the construction of the Globe Theatre on Bankside.

layhouse in London appeared on the premises of the former Blackfriars Monastery where miracles had been performed even before the Reformation. That playhouse was built in 1576 by the actor James Burbage who called it The Theatre. The Theatre was an Elizabethan playhouse located in Shoreditch, just outside the City of London. The Theatre is considered to have been the first playhouse built in London for the sole purpose of theatrical productions. The Theatre's history includes a number of important acting troupes including the Lord Chamberlain's Men which employed Shakespeare as actor and playwright. After a dispute with the landlord, the theatre was dismantled and the timbers were used in the construction of the Globe Theatre on Bankside. The design of The Theatre was possibly adapted from the inn-yards that had served as playing spaces for actors. The building was an almost round wooden building with three galleries that surrounded an open yard. The Theatre is said to have cost £700 to construct. It was a considerable sum for the age. Later, there appeared other playhouses – The Rose, The Curtain, The Swan, The Globe. There was a time when there were 9 playhouses in London alone. The playhouses did not belong to any definite company of actors. They traveled from place to place and hired a playhouse for their performances.

2. Actors and Society

During the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the Poor Laws provided that paupers, beggars and vagabonds should be sent to prison as tramps. The profession of a travelling actor became dangerous. Theatrical companies had to find patrons among the nobility. With a letter of recommendation from their patron, they got the right to travel and perform. Thus, some actors called themselves ‘The Earl of Leicester’s Servants’, others – ‘The Lord Chamberlain’s Men’. In 1583 the Queen appointed certain actors ‘Grooms of the Chamber’. And though the word ‘groom’ originally meant a man or a boy in charge of horses, now it got a new meaning – that of a provincial actor.

The worst enemies of actors were Puritans. They formed a religious sect which wanted to purify the Church of England from some forms which the Church had retained from Roman Catholics. Petty bourgeoisie needed a “cheaper Church” and hoped that they would become wealthy through careful and modest living. These principles, though highly moral at first sight, resulted in a furious attack upon the stage. Actors were actually locked out of the city because Puritans considered acting to be a menace to public morality.

The wealthy merchants also attacked the drama because plays and playgoers caused them a lot of trouble: the profits on beer went to the proprietors of the inns, not to the brewers. Also, all sorts of unwelcome people came to the playhouses. It turned out that beggars, bullies, pickpockets, drunkards and thieves were as fond of entertainment as ladies and gentlemen. What is more, during the hot months of the year, the strolling actors spread plague. That is why Town Councils and other administrative bodies quite reasonably wanted to get rid of actors.

Had it not been for the Queen herself and her courtiers, whose way of life provided more time for entertainment, the Corporation of London might have succeeded in prohibiting plays and actors altogether. As it was, the Queen and her court patronized and protected the more reputable theatrical companies. Even so, the Corporation of London made things hard enough for them, and to avoid some of their difficulties, actors tended more and more to set up their stages not in the City itself, but just outside, where the Lord Mayor had less control.

T

3. London theatres

owards the end of the 16th century, most of the playhouses were removed from the city proper. A typical playhouse of the time was circular, with three galleries running along the walls. Inside, there was a wooden stage with a roof over it, which was supported by two columns, or pillars. The open yard in front of the stage was cobbled and provided standing room for those paying a penny. The stage itself was high, with a skirt of cloth, hanging down to the ground. There used to be several sets of hangings – in different colours for different plays. Black hangings were used for tragedies; comedies, histories or pastoral plays used red, white or green hangings. At the back of the stage there were two doors which led to the ‘tiring house’ where actors changed costumes, or attired themselves. Actors usually wore expensive clothes which they got as gifts or bought at a low price from their patrons. Today, it is called backstage. The doors were large, so that the scenic properties could be easily carried through. An old playhouse inventory lists trees, thrones, tombs, chariots and other things. Actors usually wore expensive clothes which they got as gifts or bought at a low price from their patrons.

Every playhouse had a flag, and if a performance was expected, the flag was hoisted above the theatre. On the previous day, notices advertising the play would have been put up. Plays were not put on for a run, as they are nowadays. Two or three consecutive performances of the same play would be an exception. There were many revivals of the established favourites, but, needless to say, new plays were always a great attraction, and for these the fee was usually doubled. At the end of the 16th century, there was an entrance fee already.

Theatres or playhouses were usually situated on the southern bank of the Thames. Before and after a play, the Thames boatmen gathered at landings to pick up customers.

The audience entered a playhouse through the main entrance, as a rule, though certain privileged people were admitted through the tiring-house door at the back of the stage. They paid the highest prices to be allowed to sit in the gallery over the stage, or even sometimes – upon the stage itself. According to one contemporary writer, they were often a nuisance, not because they took up too much room, but because by talking and playing cards and showing off their clothes they drew too much attention to themselves. But the ordinary people went in through the main gate and paid a penny which enabled them to go into the yard. It was the cheapest part of the house and the spectators were contemptuously called ‘groundlings’. For another penny, the audience were allowed into the galleries where they either stood or, for a third penny, could sit on a stool. One of the galleries was divided into small compartments that could be used by the wealthy and aristocrats. The sitting capacity of Shakespeare’s famous theatre, The Globe, was about 2500 people. The audience consisted chiefly of men. Women did sometimes go to public playhouses, suitably escorted, but generally it>

Before the beginning of a performance, one of the actors would blow the trumpet three times. At the third sounding, the play would begin. After the performance there came the Jig, which was a jolly dance. A German visitor wrote about the Jig: ‘At the end of the play, two or three actors in men’s clothes and two in women’s clothes performed a dance, as is their custom, wonderfully well together.’ This customary after-piece was usually a rhyming farce on some topical theme. After that, the audience would leave. The boatmen ferried people back to the city

N

4. William Shakespeare (1564-1616)

ow let us speak about the greatest of all dramatists of the English Renaissance – William Shakespeare. Various ages have found various things in Shakespeare. The 18th century writers of the Enlightenment saw in him “just observation of general nature”. The Romantic age admired his freedom from literary convention. The later 19th century critics admired the delicate and complicated psychological insight of his characterization. All ages have admired his command of the language. By modern critics he is presented as the writer and philosopher who is deeply concerned with the moral basis of life. The key concepts of his plays are Nature, Order, Truth, Right and Wrong.

But did this man of genius really exist? Some critics claim that it>

One of the possible explanations is that at the time no-one even thought of publishing drama. Each dramatist wrote for his company of actors, and as long as the company had the text, it had the monopoly for staging the play. Publishing it, would have only played into the hands of the rival companies. Yet, 20 plays, several poems and sonnets were published during Shakespeare’s lifetime. After his death, his friends published several other plays in what is known as the ‘First Folio’.

As for the question ‘How was one man able to write so many plays?’ – the answer is fairly simple. Like any other dramatist of the time, Shakespeare mostly did patching and was known as a play-patcher. That is, he took well-known stories and adapted them for the stage. In 1577 Holished published his Chronicles which served as a major source for Shakespeare’s history plays. Two years later, in 1579, there came a publication of North’s translations from Plutarch – that was yet another source for Shakespeare.

What do we actually know about the man called William Shakespeare?

- Childhood and youth

He was born in Stratford-on-Avon, Warwickshire, in 1564. John Shakespeare, the poet’s father, was engaged in wool industry. He had some pasture land of his own, and also rented a house and land belonging to Robert Arden, whose younger daughter Mary later became his wife. John Shakespeare was elected alderman and by the time their eldest children were born, he acted as bailiff. Some documents of the time indicate that John Shakespeare was illiterate and in documents marked his name with a cross. John and Mary Shakespeare had 8 children – 4 boys and 4 girls. The first two daughters died in infancy. The third child born to them was a son who was named William.

William was a boy of free and open nature, much like his mother, who was a woman of a lively disposition. In his boyhood and youth, William was an inquisitive child: he knew the name of every plant in the woods and in the fields. Later, when he started writing plays, he displayed that knowledge. For example, in Hamlet, when Ophelia goes mad and walks pretending to pick flowers, she mentions the wild flowers that used to grow in Stratford and the neighbourhood. At the age of 7, William was sent to the local Grammar School where the boys were taught ‘the three R’s’: reading, writing and ‘rithmetic. Besides, they learned elementary Latin and Greek. As his contemporary, Ben Johnson, later wrote, ‘Shakespeare knew little Latin and even less Greek’. Ben Johnson had every reason to say so as he himself had gone to the best London school and could freely speak those two languages. On the other hand, William’s teachers were university graduates and gave him the basic knowledge of literature, history and geography which he deepened later.

In Shakespeare’s time, there was much guesswork in the way children were taught to read. Reading was sometimes the same as learning by heart. The first book was called The Horn-Book. The hornbook was a form of ABC book. It consisted of a piece of parchment or paper pasted onto a wooden board and protected by a sheet of horn. The text usually started with a cross in the top left-hand corner. It was followed by an alphabet, vowels, syllables, and the Lord’s prayer. Shakespeare mentions the Hornbook in his play Love’s Labours Lost.

William saw performances produced by travelling actors who came to Stratford. He was still a boy when he began to set and produce plays even though he had to work hard in his father’s business. Probably, it was also the influence of what he had seen when the Queen visited the nearby castle of Kenilworth. The stately ceremonies, the shows and plays were given in her honour, must have been imprinted in his memory. Later he showed both professional travelling actors and amateurs as characters of his plays. Travelling actors come to the Castle in Hamlet and perform a tragedy, as required by Hamlet. In the comedy Midsummer Night’s Dream a group of amateurs are busy preparing a play for the Duke to be performed on his wedding day.

Upon the wide margin of the Bible belonging to Shakespeare, one can see some drafts of play-bills. One of the play-bills announces that a sad play is to take place in Ann Hathaway’s land. Ann Hathaway was the daughter of a farmer in the village of Shottery, a short distance off Stratford. She was 8 years older than William, but they fell in love with each other and got married in 1582. At that time, Shakespeare was already writing poems. Poetry was so popular and common that Ann Hathaway expressed her feelings towards Shakespeare in verse:

And proud thy Anna well may be

For queens themselves might envy me

Who scarce in palaces can find

My Willie’s form with Willie’s mind.

The first child born to them was their daughter Susanna (1583). Two years later Ann bore him twins, a boy and a girl – Hamneth and Judith. (Unfortunately, Hamneth died at the age of 11.) It was then that the Shakespeares faced hard times. The rich landlord Sir Thomas Lucy, started a conflict with the Shakespeares over the land they had. The trouble was that William was an actor, though an amateur and Sir Thomas Lucy was a Puritan. As a result, the Shakespeares lost their land and became poor. William worked as an assistant teacher in the Grammar School, but the pay was low and he had to look for another job. Shortly after the birth of the twins, Shakespeare left for London.

- Starting a career in London

Little is known about the next years of his life. There is evidence that he worked as a secretary to a nobleman, bought and sold houses, was a buccaneer, an actor and a playwright. Once a year he would return to Stratford and then leave for London again. His plays King Henry VI and King Richard III were performed in London. It was there that Shakespeare met the actor Richard Burbage, whose father had built the Theatre and whom he had met in Stratford before. Burbage became his friend and the leading actor of the company. Shakespeare was quite a good actor himself, but it often happens even now that the playwright takes the shortest part for himself, leaving the principle ones to others. Thus, in Shakespeare’s company, the first Othello and the first Romeo was Richard Burbage. As for Shakespeare, we only know that he played the part of the Ghost of Hamlet’s father.

Little is known about the next years of his life. There is evidence that he worked as a secretary to a nobleman, bought and sold houses, was a buccaneer, an actor and a playwright. Once a year he would return to Stratford and then leave for London again. His plays King Henry VI and King Richard III were performed in London. It was there that Shakespeare met the actor Richard Burbage, whose father had built the Theatre and whom he had met in Stratford before. Burbage became his friend and the leading actor of the company. Shakespeare was quite a good actor himself, but it often happens even now that the playwright takes the shortest part for himself, leaving the principle ones to others. Thus, in Shakespeare’s company, the first Othello and the first Romeo was Richard Burbage. As for Shakespeare, we only know that he played the part of the Ghost of Hamlet’s father.Shakespeare soon won the reputation of a play-patcher, then he began to write plays of his own, based on familiar stories. If, at the time, you had asked a Londoner where to find master Shakespeare, he would have shrugged his shoulders. But if you had asked him about Hamlet, he would have explained that that was a Danish prince who had gone mad and had been sent to England. The Londoner would have shown you The Globe where the play was often performed.

‘Lord Chamberlain’s Men’, the company Shakespeare belonged to, had to pay almost all the money they earned to the owners of playhouses. That is why it was decided to build a playhouse especially for the company and let the actors get a fair share of the profit. The Globe opened in the autumn of 1599 with Julius Caesar – one of the first plays staged. Most of Shakespeare's greatest plays were written for the Globe, including Hamlet, Othello and King Lear.

- Tragedies

At that time, Shakespeare was already quite famous. Towards the end of the 16th century, the London stage shook with his plays – comedies and, especially, tragedies. They were performed at the royal court, in noblemen’s houses, in universities. Once, Hamlet was performed on board a ship. Shakespeare was known on the Continent, even as far as Bohemia (the present-day Czech Republic). Who did he write for? – Mostly, for the audience that would come to The Globe. Shakespeare could please both the groundlings and the lords. If we look back at his most tragic plays, Hamlet and King Lear, let alone comedies – The Twelfth Night, for instance, – we will see that one of the characters is a fool, or a jester. The most moving scenes are mixed with ‘indecent jesters’. Once, at the request of a Lady of Honour, Shakespeare dropped out the graveyard scene from Hamlet. The audience roared wild, threatening to bury the actors, the lady and the author, if the grave-diggers were not restored.

One of the most exciting and moving tragedies is Romeo and Juliet. It has long become a symbol of love and devotion. The name Romeo has become nearly synonymous with “lover.” Romeo, in Romeo and Juliet, does indeed experience a love of such purity and passion that he kills himself when he believes that the object of his love, Juliet, has died. Romeo’s deep capacity for love is merely a part of his larger capacity for intense feeling of all kinds. Love compels him to sneak into the garden of his enemy’s daughter, risking death simply to catch a glimpse of her. Anger compels him to kill his wife’s cousin to avenge the death of his friend. Despair compels him to commit suicide upon hearing of Juliet’s death. Such extreme behavior dominates Romeo’s character throughout the play and contributes to the ultimate tragedy that befalls the lovers.

As for Juliet, she is presented as a young girl, barely 14 years of age, who is suddenly awakened to love. After Romeo kills Tybalt and is banished, Juliet does not follow him blindly. She makes a logical and heartfelt decision that her loyalty and love for Romeo must be her guiding priorities. Essentially, Juliet cuts herself loose from her parents and her social position in Verona—in order to try to reunite with Romeo. When she finds Romeo dead, she does not kill herself out of weakness, but rather out of an intensity of love. Juliet’s development from a naïve, wide-eyed girl into a loyal and capable woman is one of Shakespeare’s early triumphs of characterization. It also marks one of his most confident and treatments of a female character.

Shakespeare’s tragedies, and sometimes comedies, might have been the result of deep personal experience. It is known that, apart from his very young days, he>

Tired with all these, for restful death I cry,

As, to behold Desert a beggar born,

And needy Nothing trimm’d in jollity,

And purest Faith unfaithfully forsworn,

And gilded Honour shamefully misplaced,

And maiden Virtue rudely strumpeted,

And right Perfection wrongfully disgraced,

And Strength by limping Sway disabled,

And Art made tongue-tied by Authority,

And Folly doctor-like controlling Skill,

And simple Truth miscall’d Simplicity,

And captive Good attending captain ill:

Tired with all these, from these would I be gone,

Save that, to die, I leave my love alone.

At the same time, the effort to avenge the wrong, only creates new crimes – that is shown in Julius Caesar. Shakespeare stresses that murder is not a way out. And in search of an answer there comes Hamlet. In the tragedy man’s existence itself is questioned. The famous line from Hamlet’s soliloquy ‘to be or not to be’ has long become a saying.

Whether ‘tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune.

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing, end them.

In the same soliloquy, Hamlet says: ‘Thus conscience does make cowards of us all’. In another tragedy, Macbeth is also tortured by the pangs of conscience. Thus, it is conscience that appears to be the driving force of the Shakespearean tragedy. ‘A sea of troubles’ which Hamlet speaks about brings into collision different people. By the end of each tragedy, the stage is full of corpses – again, unlike in the Greek tragedy. But Shakespeare shows that the noble heroes do not kill for the sake of revenge only, they kill for the sake of justice and then they perish, too.